'My Jesse was still at war'

Warning: the following story discusses suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, support is available at Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. If you are an Australian veteran or family of a veteran, you can also call Open Arms, Veterans & Veterans Families Counselling Service, on 1800 011 046.

The Australian War Memorial has worked with veterans and their advocates to commission a work of art to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war and military service. The art work represents those affected by operations and during training; in war and on peacetime service.

Learn more.

Connie Boglis was about to board a plane to Athens when her phone started buzzing.

There were so many messages coming through, she couldn’t focus on just one.

“I was half way to Europe, and I was standing in line at Dubai airport with my parents, waiting to get on to a flight to Greece to surprise our family,” she said.

“I thought I’d quickly check to see if anything had come through, and my phone messages didn’t stop.

“It took about a minute or so, and the first message I saw said: ‘Connie, my condolences. Sorry to hear about Jesse. Here for you if you need me.’”

Connie and Jesse. Photo: Courtesy Connie Boglis

Connie was stunned. Her former partner, Jesse Bird, a 32-year-old Afghanistan veteran, had died at home in Melbourne on 27 June 2017.

“I literally dropped on my knees in line to board the plane,” she said.

“I didn’t know what had happened, but when somebody says condolences, you know that means they have passed away. And that was all I could think of, that word ‘condolences’.

“Jesse and I were on a break, and I was still very much in love with him, and hopeful that we would come back together and he would get the help he needed for us to go on.

“I spent the six-hour flight to Athens crying, looking out the window in a dazed numbness for answers, and I remember asking: ‘Jesse, what happened to you?’

“It was so very surreal, and I was just trying to piece everything together … Had he been in an accident? Had he been hit by a car?”

When the plane landed in Greece, Connie tried desperately to contact Jesse’s family. Jesse, the love of her life, had died by suicide, alone in his St Kilda apartment.

Jesse with Connie's dog Meeko. Photo: Courtesy Connie Boglis

Connie was absolutely devastated.

“He was just one of those guys. He had a big, loud laugh and a big personality. And he loved all those around him – friends and family. And he was very easy going, very charming.

“He’d walk into a room, and he was able to just hug people, and have a laugh, and be the centre of attention.”

They’d met in April 2014, while Connie was preparing to go on a three-month holiday overseas.

“Our first date was two or three days before I left,” she said.

“We met on the grounds of the arts precinct at the Abbotsford Convent Gallery [in Melbourne].

“We had lunch, and we just walked around the animal farm there, and got to know one another. It was lovely.

“I spoke about everything that mattered to me – from animal cruelty, to travelling, career, and my love for helping others.

“Jesse told me that he worked in Nauru as part of the Emergency Response Team, and although it was financially rewarding, it gave him no career satisfaction.

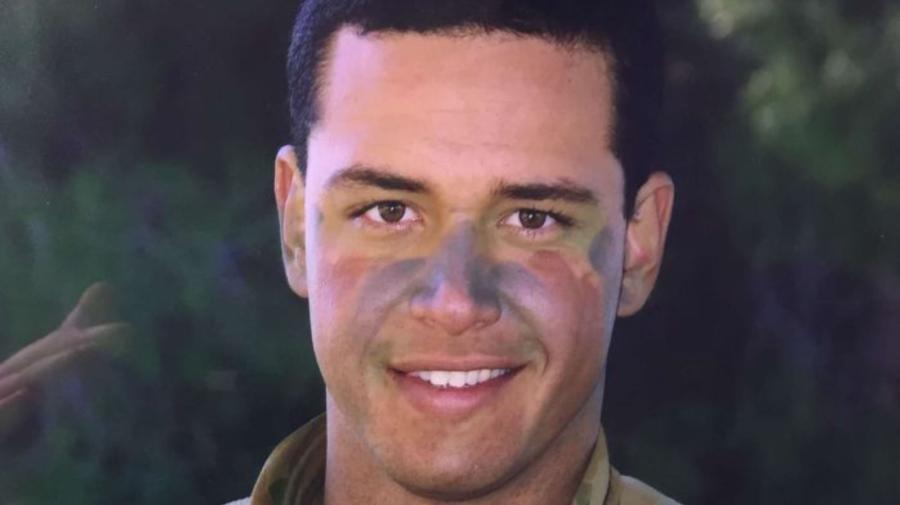

Jesse in Afghanistan. Photo: Defence

“He then spoke about being a veteran and having served in Afghanistan. He could not speak highly enough of the Army, hoping one day he would return to his role in which he felt a sense of purpose as a soldier. To quote Jesse, he said: ‘It’s all I know how to be, Connie.’

“As naive as I was that day about what Jesse was going though, I felt so proud to be walking in his company. Upon reflection, I think he had dissociated so much from his trauma that he just hadn’t even scratched the surface of his time in the ADF.

“Our second date was three and a half months later when he picked me up from the airport at two in the morning. And there we had our first kiss.

“We had gotten to know each other as pen pals with overseas phone calls and messages.

“We’d made the time to stay in touch every day through all the different cities, countries and time zones I visited, whether it be a message or a phone call.

“We grew to fall in love with one another, and it was really beautiful.

“But there was a side of Jesse that not a lot of people got to see, including myself. He was very guarded with his emotions and I just thought in time he would let me in.”

Jesse in Afghanistan. Photo: Defence

Jesse had deployed to Afghanistan in 2009 as a private with the Townsville-based 1RAR infantry battalion. He had been shot at by insurgents during firefights and had faced the constant threat of improvised explosive devices, one of which killed his close friend, 22-year-old Benjamin Ranaudo.

When Jesse returned from Afghanistan in 2010, his family knew straight away that something was wrong. He was “not the same person” who had joined the army as an athletic, charismatic and confident young man in 2007.

After leaving the army in 2012, Jesse struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suffered from night terrors, anxiety, alcohol abuse and depression. Only after meeting Connie, did he receive this diagnosis.

“He hid his pain really well,” Connie said. “So I didn’t really see Jesse’s mental health barriers come to the surface until a year after we met and Jesse moved in with me. He had kind of kept his PTSD under wraps in the sense that he had a routine: he’d be at the gym every day, he’d be at work, and he had that stability around him.

“But then everything changed.”

Connie and Jesse on Connie's 34th birthday. Photo: Courtesy Connie Boglis

They were in Queensland for Christmas with Jesse’s family when Jesse had headed off to Nauru for work, and Connie headed back to the home they shared in Melbourne.

“Jesse was working two weeks on and two weeks off, and I wasn’t expecting to see him again for a couple of weeks, but he arrived back home in Melbourne two days later,” Connie said.

“He’d been told he’d lost his position there, and that he was no longer needed, so Jesse became unemployed.

“I don’t think he’d ever been without a job – he’d always had that security, and he’d always had that stability – and that unemployment status hit him really hard.”

Jesse struggled to find meaningful work.

“As I saw more of Jesse, I saw everything,” Connie said.

“The honeymoon period was definitely over. Jesse had nightmares most nights and would wake up dripping wet.

“When he described his dreams to me, they were horrific. If he wasn’t being chased, attacked or tortured, he was having to fight to save people from being killed.

“My Jesse was still at war…

“But he was not only unpacking the mental health barriers that he faced, he was also unemployed with dwindling savings, and the pressure of finding gainful employment in a field he enjoyed wasn’t an easy one.”

Jesse and Connie at Jesse's surprise 30th birthday. Photo: Courtesy Connie Boglis

Jesse and Connie. Photo: Courtesy Connie Boglis

Jesse spent years trying to get financial help and to get the Department of Veterans Affairs to recognise his physical injuries and now his PTSD, anxiety, depression, alcohol addiction, all resurfaced.

“He was never one to seek assistance, and he was always there for everybody else, so it was the biggest slap in the face, that when he really needed help, it wasn’t there,” she said.

“He’d done his time. He’d been in a war-torn country. He’d been shot at. He’d had friends blown up by IEDs. He’d done his job, so to speak, and now he wanted that security, that safety net of coming home and attempting to transition into civilian life so that he could start a future with a family. But he was denied that.

“I soon became more his mentor, support person, nurse, employee consultant; everything else, except his partner.

“His pain was mine, and I worried for him.

“But as a partner, I too was forgotten.

“The role a partner plays in a veteran’s life are not recognised or understood as it should. It is the support around a veteran that keeps them alive in times of distress and need.”

Jesse died just weeks after being told his permanent impairment claim had been declined. He had just $5.20 left in his bank account.

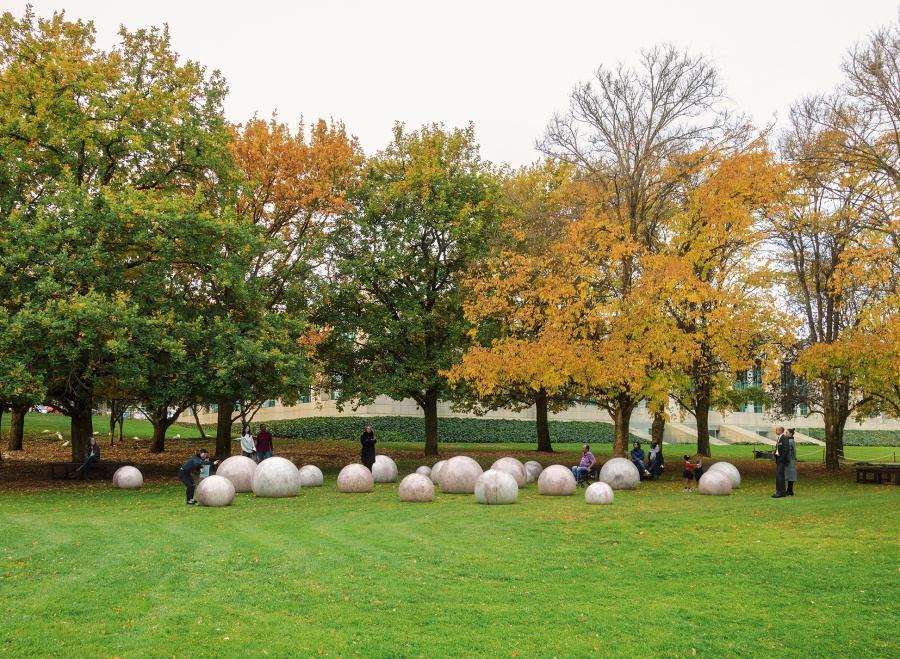

Connie and Jesse's mother Karen with a maquette of Alex Seton's sculpture For Every Drop Shed in Anguish. The sculpture will be installed in the grounds of the Memorial in 2023.

Today, Connie is a tireless advocate for Australian veterans and their families.

She is one of the people who have been working with the Australian War Memorial to have a Sufferings of War and Service sculpture on the grounds to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war, military service and back home.

Connie, along with Jesse’s mother Karen and his sister Kate, was part of a committee that helped secure funding and provide the Memorial with feedback and insights that led to the selection and commission of a work by artist Alex Seton.

For Every Drop Shed in Anguish, a field of sculpted Australian pearl marble droplets, will take the artist two years to create and will be installed in the Memorial’s Sculpture Garden in 2023.

For Connie, the sculpture is particularly poignant.

“I didn’t get to go to Jesse’s funeral, so that is a place I can visit him,” Connie said.

“But this sculpture is not just for us; it’s for everyone.

An artist's impression of Alex Seton's For Every Drop Shed in Anguish which will be installed in the Sculpture Garden at the Memorial in 2023.

“There are so many people, so many partners, so many silent voices that have come to me in the past five years since losing Jesse, and shared their grief, shared their lack of acknowledgement, and shared their stories.

“It’s so important to give families a place to grieve and acknowledge their suffering. But it’s not just about suicide and mental health, it’s also about suicidal ideation, and those veterans and ADF members who are still alive, and who are still struggling every day because of their service.

“It’s a place to give them hope, and for them to remember how far they have come, but it’s also a place to educate children and all those who come through the grounds and want to learn about our history, the real history of the war that comes home.

“It’s in your face and it’s meant to be.

“This is the untold truth that gets missed; that the transition back home is still a war zone for many people, and that their families go to war too.

“I like that this sculpture has no heroes. It is a space for everyone to be acknowledged or educated.

“Whether a veteran, family member, partner or teacher, you can grieve, remember and educate our Australian community on the ultimate sacrifice of war.

“The stone itself embodies our experiences: the marble is raw, it has flaws, and it changes over time, and it will be perfectly positioned at the Australian War Memorial to continue the conversation for decades to come.”

The Australian War Memorial has commissioned a work of art to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war and military service. The sculptural installation, For Every Drop Shed in Anguish, by artist Alex Seton, will provide a place in the Memorial’s Sculpture Garden for visitors to grieve, to reflect on service experiences, and to remember the long-term cost of war and service. A field of sculpted Australian pearl marble droplets, it will be made by the artist over the next two years and will be installed in the Sculpture Garden in 2023. For more information about the Sufferings of War and Service sculpture, visit here.

If you, or someone you know requires support, please contact:

Defence All-hours support line – The All-hours Support Line (ASL) is a confidential telephone service for ADF members and their families that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week by calling 1800 628 036.

Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling Service provides free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. They can be reached 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit the Open Arms website for more information.

DVA provides immediate help and treatment for any mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. If you or someone you know is finding it hard to cope with life, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254. Further information can be accessed on the DVA website.