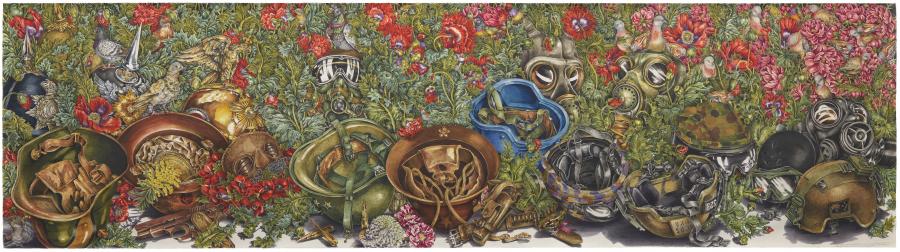

Cure for Pain Part 2: Flowers

Cure for Pain by eX de Medici.

ART96843

Cure for pain draws its title from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), which can be found growing in suburban gardens in inner Canberra. The flowers are a remnant of wartime cultivation by the then Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. A tall pale green plant with twisting leaves, the opium poppy bears a flower with striking colours, ranging from dark red petals with the inner edge in rich purple, through to pale purple, or candy pink. At the centre of the flower is a distinctive, cup-shaped seed pod with a crown that, when cut, oozes a milky, sticky sap. It is this sap that is used in the production of opiates, most commonly laudanum, morphine, and heroin. Opium poppies do not make a great cut flower – the stems quickly go limp, and the petals fall off. So the poppies that are seen in Cure for pain were drawn by eX de Medici from those Canberra gardens. But in the new context of Cure for pain, the opium poppy is far from a decorative cottage flower, instead bearing a rich military history.

The British desire to control the import of opium into China triggered the Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60). In a military context, the power of opium to provide pain relief was embraced, but with some dire consequences. As researcher David T. Courtwright explained, during the American Civil War (1861–65) sick and wounded soldiers were injected with morphine, and then became addicts, while veterans were also given opiates. In the Australian experience of the First World War, the use and the intermittent availability of morphine at each stage of evacuating the wounded was complex, and as the official history records, “many men died from its misuse, many others sustained great needless pain.” Heroin was also a feature of the Vietnam War (1962–75), during which the Golden Triangle of Burma, Thailand and Laos was a source of fine-grade heroin that was sold directly to American GIs. According to research by Alfred W. McCoy, by mid-1971 it was estimated that between 10 and 15 per cent of lower-ranking American soldiers were using heroin.

The opium poppy is synonymous with conflict in contemporary Afghanistan, a country renowned for its vast crop. In 2011 – at the time Cure for pain was created – the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reported that Afghanistan accounted for around 90% of the world’s opium production. Australia was involved in the conflict in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2014, and since 2015 has had a non-combat role with the NATO mission, Operation Resolute Support. In an attempt to prevent insurgents from profiting from opium production and narcotics manufacture, Australian soldiers have targeted traffickers and drug labs.

Closer look at the flowers in the artwork Cure for Pain by eX de Medici.

ART96843

Flowers are rich symbols of military conflict, but also of nationhood. In the centre left of Cure for pain is a sprig of golden wattle, the floral emblem of Australia. In 1917 Banjo Patterson called for “A spray of wattle bough / To symbolise our unity, / We’re all Australians now.” The symbolism of the golden wattle is not confined to nationalist fervour and the sense of unity that war can generate. It also conjures Australia’s dark history of frontier violence, explored in Bruce Elder’s Blood on the wattle: massacres and maltreatment of Aboriginal Australians since 1788. Adding a commemorative reading to the watercolour is the inclusion of red Flanders poppies, placed around the First World War helmets. A symbol of death and remembrance, those seen in Cure for pain are drawn from poppies laid at the Australian War Memorial's Hall of Memory.

Placed at the bottom centre of Cure for pain are a white chrysanthemum and a pink-and-white variegated camellia. In Japan both flowers are symbols of death, but the white chrysanthemum is also the emblem of the White Chrysanthemum Society of Bereaved Families, which was formed by the families of executed Japanese war criminals. This subject is explored in Nariaki Nakazato’s study Neonationalist mythology in postwar Japan. The white chrysanthemum is also a symbol of the Yakusa, a Japanese crime syndicate, whose dead member’s tattooed bodies are flayed and preserved. The two flowers have been placed in front of a grenade from the Solomon Islands, where the Americans and Japanese fought during the Second World War, represented here by their helmets. Bullets from the Steyr, the Australian army standard weapon, and two Australian woma, or pythons, are around the flowers. This grouping also references the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands, in which the Australian Defence Force participated from 2003 to 2013 – including helping with the safe detonation of unexploded ordnance left over from the Second World War. For de Medici there is a paradox in war flowers being associated with men, for as she observed, the flower is reproductive (feminine) but war is destructive.

Cure for pain was generously donated to the Memorial, through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, by Erika Krebs-Woodward in 2016. Cure for pain is on display for the first time in the exhibition The deceiving eye, located on the Mezzanine Gallery of Anzac Hall until 11 September 2017.