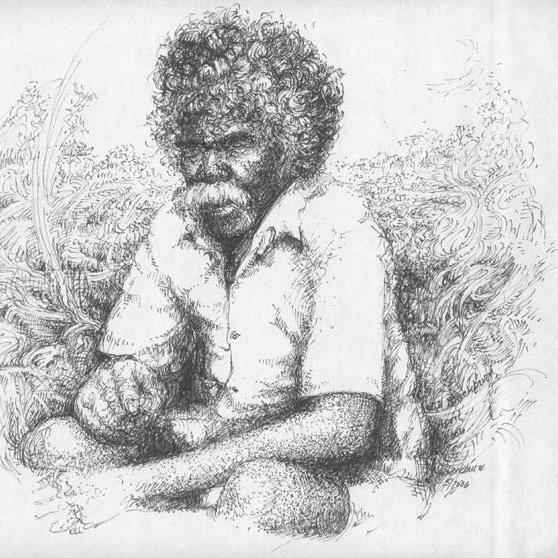

David Burrumarra: an unforgettable man

Warning: this article contains images of deceased persons.

David Burrumarra would often parade around his community dressed in military costume, sporting a pith helmet, and proudly displaying his medals.

The Yolngu philosopher, diplomat and leader would peer into the crowds with his binoculars while speaking to the public through a megaphone.

Visitors to Elcho Island would remain transfixed as he spoke, and gaze in awe at his tall, stately figure.

Danusha Cubillo, a researcher at the Australian War Memorial, was inspired by Burrumarra’s story while conducting research into Indigenous service during the Second World War.

“Burrumarra was known for his unforgettable personality, and his life and work, which had a major impact on the history of Arnhem Land,” she said.

“He dreamt of a unified Australia where Aboriginal culture and heritage had pride of place, and he helped defend his Country during the Second World War.

“Although he doesn’t actually have a service number, he still contributed to the war effort, and he still served his Country.”

A proud Larrakia woman, Cubillo has been working with the Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer, Michael Bell, to research and identify Indigenous Australians who have served or are still serving.

She was seconded to the Memorial from the Department of Defence through Defence Indigenous Affairs in 2020, to work on the Memorial’s Second World War Indigenous Service List.

Burrumarra’s story is one of the many that have encouraged and inspired her during her work.

“David Burrumarra was born in 1917 during rarrandharr, or the dry season, at Wadangayu, on Elcho Island, in the Northern Territory,” Cubillo said.

“He was part of the Warramiri clan, and was the son of Ganimburrngu (Lanygarra) and his wife Wanambiwuy, a Brarrngu woman.

“He was very well respected in his community, and when he was born, his grandmother bestowed upon him his name, Burrumarra, which refers to the skeleton of the large white-tailed stingray.

“His family already had close ties with the whale and the octopus – which were their totems – and so those three marine animals were very sacred to him.”

He was educated in English language and culture by Methodist missionaries in Milingimbi, Yirrkala and Galiwin’ku and was chosen by his family to learn about non-Aboriginal ways.

When the Second World War broke out, Burrumarra was one of the thousands of Indigenous Australians who used their traditional skills and knowledge to help defend their Country.

In 1943, Burrumarra supervised Yolngu workers in the north-eastern corner of Arnhem Land as they worked on the construction of the Royal Australian Air Force Base at Gove.

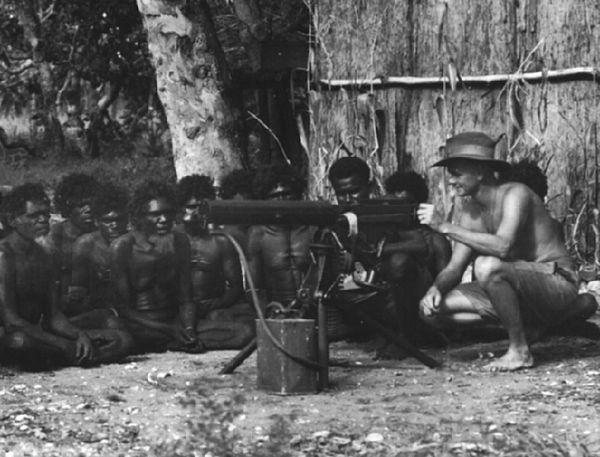

Burrumarra also joined the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit and was involved in postal deliveries and coastal surveillance between Yirrkala, Milingimbi and Elcho Island.

“He was among 50 Aboriginal people and several white non-commissioned officers who patrolled the coastal areas between Yirrkala, Milingimbi and Elcho Island, searching for signs of Japanese landing craft or submarines,” she said.

“They reported enemy locations and movements towards Darwin, and were also trained to fight as guerrilla agents, using traditional weaponry – spears, woomeras, things like that – so they could engage in combat if a landing party managed to alight on shore.”

Patrols were conducted in extremely harsh conditions, and the unit members needed to be resourceful, motivated, and independent.

“Burrumarra was selected to be part of this group because of his knowledge of the local area and because of his ability to survive in the bush,” Cubillo said.

“Traditional people know bushcraft, so they are able to get by with very little, and that’s why Burrumarra was chosen to be part of the unit.

“It was composed mainly of Aboriginal people from the Northern Territory, and their knowledge of the local area, as well as their tracking, outback survival and bushcraft skills, made them ideal candidates to help defend the north coast of Australia.”

Similar units were formed on Bathurst Island, Melville Island, the Cox Peninsula and Groote Eylant.

The Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit was an irregular warfare unit that was formed in 1942 under the command of Squadron Leader Donald Thomson, an anthropologist before the war who had extensive experience working with the local Yolngu people in the 1930s. The were involved in coastal surveillance between Yirrkala, Milingimbi and Elcho Island.

After the war, Wangurri leader Batangga requested Burrumarra be relocated to Galiwin’ku, on Elcho Island, to serve as a community liaison officer. He would prepare correspondence for community members using a typewriter he owned, and he became the first Yolngu teacher’s assistant at the local school.

“Burrumarra was fluent in eight Yolngu languages, as well as English, and his knowledge and status within his community made him well respected by clan leaders, who looked to him as a mediator between his people and visitors to the area,” Cubillo said.

“He wanted to ensure children knew the importance of their connection to the land and sea and their role in being custodians of this heritage.”

When not teaching or supervising correspondence lessons, Burrumarra travelled with missionary Harold Shepherdson, helping to deliver vital supplies to outstations, and to conduct church services.

Burrumarra was a member of the council of AIAS (Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies) from 1974 to 1976 and served as a member of the AIAS Aboriginal Advisory Council from 1975 to 1979.

He designed a flag using Warramiri and Australian symbols to represent partnership and understanding between Aboriginal people and the European newcomers. This flag, painted on board, is on permanent display at the law school of the University of New South Wales.

“It was also Burrumarra’s dream that Indigenous artwork be displayed on the walls of all government buildings where decisions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were made,” she said.

“This was the 1970s, and there were barely any Aboriginal artworks to be seen on the walls; so he had this idea that in every single office where people made decisions for Aboriginal people, they should have Aboriginal art on the walls so that they could always be reminded of who they were making these decisions for. He was very passionate about making that dream happen, and I believe that dream has been achieved.”

Burrumarra was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire in 1978. He insisted the governor-general travel to Elcho Island for the investiture and that visiting dignitaries wore sacred Warramiri whale and lightning caftans that he had designed especially for the event.

Burrumarra passed away at his home on Elcho Island, on 13 October 1994.

Today, his name is one of more than 4,400 names listed on the Australian War Memorial’s Second World War Indigenous Service List. Cubillo is encouraging anyone with more information about Indigenous servicemen and servicewomen to contact the Memorial and share their stories.

“It’s about respect and giving that person their due,” she said.

“They fought for this country, and we want to acknowledge them for who they are, and be able to tell people proudly who this person was.

“Burrumarra was a very eccentric character, and he was known for his unforgettable personality.

“I could just see him polishing his medals every day, getting dressed up, and going out for another day on the town. That was just him, and people accepted it.

“He was a great conversationalist and orator, and had that charisma and that passion, and was able to influence people.

“He said his skills came from above, falling like leaves from the tree of paradise, and that he wanted people to come together as one.

“He dreamt of a unified Australia where Aboriginal culture was considered to have pride of place, and his life and work had a major impact on the history of Arnhem Land.

“He was definitely unforgettable, and I would have loved to have met him. I would have said, ‘Uncle, that is too deadly.’”

Michael Bell is a Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man and the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial. If you have information about the contributions of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served or are currently serving in the armed forces, or who have contributed to wartime efforts, he would love to hear from you. He can be contacted at Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au.