'We had the rest of our lives to spend together'

Second World War veteran Dennis Davis: “War is a terrible waste of human life.”

Ninety-seven-year-old Dennis Davis survived the siege of Tobruk and the fighting at El Alamein, but was left devastated when he received a ‘Dear John' letter from his fiancée just before Christmas in 1942.

“I’d met a nice Australian girl. We had a very good relationship, and we got engaged,” said Davis, who was born in London in 1920 and moved to Australia with his family when he was 17.

“But then I said to her, ‘If I’d been in England still, I’d have been forced into the army,’ and I thought I’d rather volunteer than be forced in later. I volunteered for the RAAF, but I failed the medical when they discovered I was colour blind. Then, of course, when Dunkirk came, I thought, well, it’s time to join up … [so] I went down to Martin Place [in Sydney] during my lunch break and enlisted in the AIF… around about June 1940.”

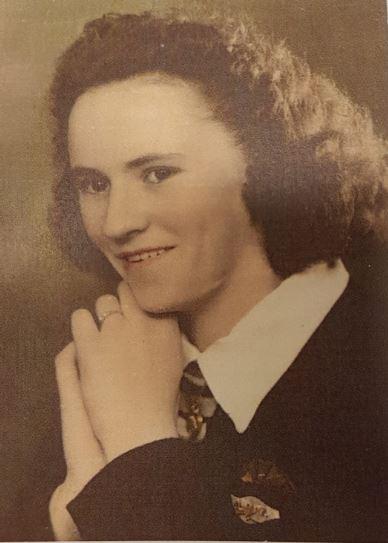

Dennis Davis with his fiancée Margaret McNally. Photos: Courtesy Dennis Davis

Davis was speaking during a visit to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. His father had served with the British Army during the First World War and Davis wanted to do his bit for the war effort. He farewelled his fiancée, Margaret McNally, and was initially assigned to the 8th Division Service Corps, where his role was to keep troops supplied with food and ammunition. He remembers being “volunteered” for the 9th Division.

“We got onto a parade one day and the colonel took the parade and he said: ‘We’re going to make a new division, the 9th Division. All volunteers, one pace forward.’ And, of course, nobody volunteered,” he said. “There were about 1,000 of us on parade, so he just told the different commanders to count their number off – ‘1 to 25, dismissed’ – and the rest of us, he told us: ‘Thank you gentlemen for volunteering, you’re now in the 9th Division.’

“Of course, that basically meant that anybody left [in the 8th Division] finished up prisoners of war in Singapore, so we were very fortunate. We didn’t think so at that stage, but certainly afterwards … well, we were the fortunate ones.”

Davis left for the Middle East and North Africa on Boxing Day 1940 and wouldn’t see his fiancée again for two and half years. She enclosed a postcard-size photograph of herself in the first letter that she wrote to him, and he kept it in his breast pocket throughout the war.

“It was a lovely photo of a beautiful girl,” Davis said. “And I never tired of displaying it with pride.”

Dennis Davis kept this picture of Margaret in his breast pocket for the duration of the war.

Thoughts of Margaret kept him going while he served with the Australian forces in Tobruk in 1941 and with the peacekeeping forces in Syria after the Vichy French forces were pushed out.

At El Alamein, Davis drove around the clock to help keep troops in the front line supplied with ammunition and food and water. But it was dangerous work, even before the second battle began on 23 October 1942.

“Two trucks were hit during a night raid,” Davis said. “Both were loaded with ammunition and both blew up together with their drivers, who were asleep in the trucks. One man was lucky, he was sleeping on the tailboard and was blown to the ground by the explosions; he was severely injured but he survived. After this disaster we realised we had to consider whether it might be better to share the tent with the scorpions or the truck with the explosives. [But] our decision on sleeping arrangements was soon changed when we shook an asp out of my blankets one evening.”

Dennis Davis during the Second World War.

It was during the battle of El Alamein that a letter home changed everything. “While we were at Alamein in a little platoon of 11 men, we were carting ammunition to the front line and we made a bit of noise; and the Germans picked us up, and we lost seven men killed or wounded that day,” he said quietly. “Only four of us survived without anything and, of course, I was quite upset about this. In writing home, you couldn’t say even where you were or anything else – but I must have said something to my fiancée: I said it looks as though it will be quite a long while before we get together again.

“She misinterpreted it and thought that I’d got a girlfriend or something, so … at Christmas time I got this ‘Dear John’ letter, almost on Christmas Eve. And, of course, that really upset me. I was devastated.

“And then I heard from my parents that she was getting married in March, and I thought, what can I do about it?

“I was getting no letters at all, but I was still writing to her, saying I still loved her, and ‘What have you done?’ And ‘Why have you made this decision?’

“Anyway, we arrived home on the 28th of February, and I thought that’s before the 1st of March, so eventually I went down to see her.

“I went straight home to my parents first, and my ex-fiancée phoned me up that day. I didn’t want to talk this thing over on the phone, so I had a brief conversation after she welcomed me home, and I just said, ‘I love you.’

“I sort of put the seed around, and the next day I went to see her, and to cut a long story short, she opened her arms and locked me in, and four days later we were married … So it was very good. It was a good end… [And] my worries were over.”

The pair married in Sydney on 6 March 1943, but were soon parted again.

Dennis Davis and Margaret McNally on their wedding day.

“I was so happy,” Davis said. “But, of course, we had to go away again after that. Those six weeks we had between returning from the Middle East and leaving for Queensland had passed so quickly. It was a happy time, but the shadow of the war was in our thoughts throughout the period. It was a sad parting for both of us.

“And then we were off up to the Tablelands to train for New Guinea. There was absolutely no similarity between New Guinea and the Middle East. In New Guinea, it was hot and humid, even at night, and it would rain at least four days out of seven. Additionally, of course, there was the jungle instead of the desert, and there were mosquitoes instead of flies, and we were in jungle greens wrapped up from the neck down, instead of khaki shorts and shirts with rolled up sleeves.”

Davis will always remember the relief he felt when the war was finally over.

“War is a terrible waste of human life,” he said. “The Japanese were starving, and they didn’t know the war was over. They used to hide in the trees during the daytime and try to knock the soldiers off at night – so we were always a bit wary when we were driving through the jungle with a whole load of food on the back, [in case we] passed Japanese [hiding] up in the trees, who didn’t know where their next meal was coming from. So it was very good when the war was over and we were back home.”

Since he enlisted in 1940, Davis had served for “five years and four months exactly” and took part in five different campaigns.

“Looking back … I can say without hesitation that Tobruk was the most arduous … [and] Alamein ran a close second,” he said simply. “Of course, for me, the greatest hardship of all was the separation from Margaret … but that was about to end and we had the rest of our lives to spend together.”