'I’m very lucky to be alive'

Second World War veteran Derek Holyoake: "It was [terrifying], but it wasn’t so bad … Other ships got sunk and got hit … It was just what happened."

Derek Holyoake was just 16 when his father sent him to join the navy in 1940, telling him that he’d be safe there during the war.

“I didn’t [have a choice],” Holyoake said with a laugh while visiting the Australian War Memorial. “My father was a World War I soldier-settler from England and my mother died when I was 10.

“When the war broke out, [my father] wanted to join the Australian Army … but he didn’t know what to do with me, so he got one of his friends with a car to drive me up to Victoria Barracks to meet one of his old British army officers there, and he expedited me into the navy.

“He put his age down to join the army and put my age up to join the navy … and that’s how I came to be in the navy. His words were: ‘I’m going to put you in the navy, son. I know you’ll be safe there.’ And that’s what he said.

“I had no option. In those days, we did what we were told, and it was just as well. He joined the army and sold the house, so I didn’t have a home to go to, so when I finished my recruit training and was posted to HMAS Hobart on the 20th of January 1941, that was my home, and my shipmates were my family.”

Now 93, Holyoake was just three months old when his family arrived in Australia in 1924 and settled on a 40-acre block at a Murrabit on the Murray River. “My mother was a London office girl, and it was so hard,” he said. “We couldn’t afford shoes, [so] we used to go to school in bare feet. And there were snakes under the house and in the wood heap, and there was no phone, no electricity, and mum used to have to go and buy unbleached calico to make our shorts and shirts.”

But life got even harder after the 10-year-old Holyoake travelled to Melbourne with his mother and three of his siblings in 1934. “[She] put us in [a church] home and then she took herself off to the Melbourne hospital,” he said. “But she never came out.”

After his mother’s death, Holyoake remained at the children’s home until he “got too old” and was sent to live with one of his father’s army friends. He was reunited with his father in Bendigo in country Victoria, but the reunion was short-lived. His father joined the army and Holyoake joined HMAS Hobart as an ordinary seaman and sailed for the Mediterranean in June 1941.

As part of the Mediterranean Fleet, Hobart supported the North Africa campaign, including operations to relieve troops from Tobruk, before being transferred to the Far East and arriving in Malayan waters in early 1942.

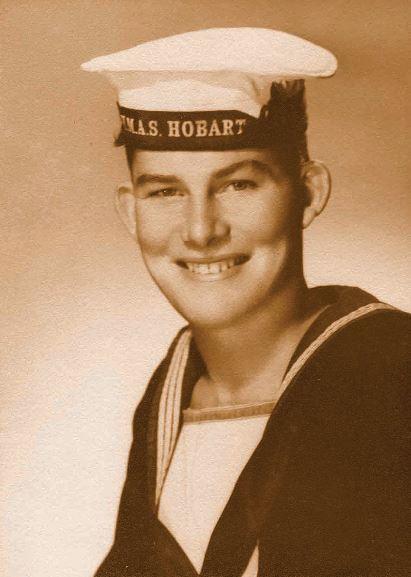

Derek Holyoake during the war. Photo: Courtesy Derek Holyoake

Holyoake remembers a close call when Hobart was fuelling alongside a tanker on 25 February 1942.

“Twenty-seven Mitsubishi high level bombers … came and all dropped a stick of bombs around the two ships and one of them hit the tanker. It went right through and exploded underneath,” Holyoake said. “I was just 17, [but] I was lucky because I wasn’t exposed. When these high level bombers drop bombs around the ship, there are a lot of splinters, and of course … people get wounded, but I was in one of the gun houses … So I was lucky.”

It was estimated that 60 bombs fell near and around the two ships.

“We had a very, very good captain, and he used to watch the bomb bay doors opening … and he’d wait,” Holyoake said. “The Japs’ high level bombers used to fly in with multiples of nine … and the leading aircraft used to drop a flare, and all the others would drop bombs together … The captain would work out where they were going to fall and he’d go full ahead on one engine, and full stern on the other, and turn the ship around like a motorboat... He was a man above men."

Hobart operated with the American, British, Dutch and Australian (ABDA) forces in the Dutch East Indies and took part in the battle of the Coral Sea as well as in operations to cover the American landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the Solomon Islands.

Holyoake recalls the Solomons campaign and the battle of Savo Island vividly. “It was like this melee,” he said. “There were ships ducking and diving, and aircraft flying around.”

He admits that it was a terrifying experience. “But what was interesting about it [is that] when you talk about people being frightened, well you’re frightened, but the gun crews and all these other guys had already been in action against the Italians in the Red Sea, and they didn’t seem to be too worried about it all, so I thought, ‘Oh, that’s what you do, is it, in a war.’

“In the morning, Canberra was on fire, the Chicago had torpedoes and big holes in the bows and the Astoria, Vincent and Quincy were sunk, and one of the American destroyers was also sunk. And the fighting went on for so long.”

Derek Holyoake, centre, visiting the Memorial with other Second World War veterans.

After surviving campaigns in the Mediterranean and Pacific, Hobart’s luck ran out on 20 July 1943 when she was hit by a Japanese torpedo.

“That was horrible, and I’m very lucky to be alive,” Holyoake said. “I’d done a course on the ship and I was taken out of the gun's crew and I was on the torpedo tubes … All the guys that were in my gun's crew were all killed, all four of them…

“I was thrown on the deck because the ship went up … The only thing that was holding the stern on was the bit of plating on the starboard side. The deck was busted. The keel was busted… Our steering was also buggered, so we couldn’t steer, and it was very tense because we only got underway at about one and a half knots or something, and you could see this great big giant oil slick behind us, and you were wondering when the next one was going to hit.

“The ship had a bit of a list on it, so I had to go down into the compartments and hook up emergency cables to hook up an oil pump to pump the fuel oil out of that tank … and I was up to my knees in sea water and fuel oil wondering when the next bang was going to come, but, anyway, we did it …

“It was [terrifying], but it wasn’t so bad … Other ships got sunk and got hit … It was just what happened.”

Hobart survived, but needed extensive repairs, so Holyoake was transferred to the corvette HMAS Rockhampton, on which he served for the remainder of the war. “We spent 15 months up in the islands following the Americans, doing their escort work and pinging for subs and stuff like that,” Holyoake said. “But it was very, very boring after being in the Hobart.”

I was up to my knees in sea water and fuel oil wondering when the next bang was going to come.

Holyoake remained in the navy after the war ended and was a member of the original crew of Australia’s first aircraft carrier, HMAS Sydney. He was promoted to lead electrical mechanic in 1949, and served aboard Sydney during her deployment during the Korean War in 1951-52. He will never forget getting caught up in Typhoon Ruth coming out of Sasebo in Japan, and the constant battle against the weather.

“It wasn’t dangerous from the enemy – we were at danger from the sea,” he said with a laugh. “I thought we were going to get sunk, the waves were tremendous.

“I had to get up at an hour before dawn and check all the communications from the flight deck up to the bridge … before they started flying at dawn. And, of course, over the 38th parallel it was snowing, and I don’t know what the temperature was, but it was about minus 17°F. The sea water was freezing and it was so cold. [They] gave us, balaclavas, and woollens, [and] I was like the Michelin man. And then, of course, the day job, I had to look after the Beaufort mounting, and if a gunsight needed a new globe or something, I’d undo a screw, and [then] put the gloves [back] on. It used to take twice as long, or four times as long to do a job [because you were] trying to keep warm.”

Holyoake spent 13 years in the navy, and didn’t see his father again until after the end of the Second World War. His father joined one of the armament regiments and was due to go to the Middle East when Japan entered the war. An officer reportedly said to him: “Trooper Holyoake, I think you’re a bit too old for this caper, so we’ll give you an easier job.” He became an army depot postman and bugler and spent the rest of the war in New South Wales.

Today Holyoake, whose oldest brother John was killed during the war, volunteers for school wreath laying ceremonies at the Australian War Memorial and attends commemorative events to remember his mates. He still considers himself lucky.