Squadron Leader Douglas Sampson and the “Camera Spies”

On 6 June 1944, Flight Lieutenant Douglas Sampson strapped into his Supermarine Spitfire Mk XI and flew from RAF Northolt in the west of London, crossing the English Channel before entering German-occupied France.

The skies were cloudy, the weather far from optimal; flying low, Sampson pushed on, aware of the importance of his mission. He was flying a final photographic reconnaissance in support of the Allied invasion of Normandy that would take place that day. While cloud cover prevented deep reconnaissance, Sampson covered the main road junctions between Coutances and Saint-Lo, keeping an eye out for the movement of German tank formations. On returning to Northolt, he saw ships spotted along the Normandy coast.

Sampson flew 24 sorties over Normandy and northern France in the three months leading to D-Day. He and others serving in photographic reconnaissance squadrons recorded the coast from Granville on the Brest peninsula up to Knokke in the north of Belgium, providing Allied commanders with valuable intelligence on German defences and reinforcements, and helping to shape Allied invasion plans.

The defences on “Juno” and “Gold”, the landing beaches for British and Canadian forces on D-Day, as photographed by a low-flying reconnaissance pilot in May 1944. (AWM2018.975.43)

It was not easy work. Photographic reconnaissance required patience, airmanship and – as the men often piloted unarmed aircraft – courage. Sampson’s Spitfire Mk XI had been adapted for photographic reconnaissance – machine guns were removed to reduce weight, increase speed and enable longer flights, while cameras were fitted in the fuselage behind the cockpit.

Photographic reconnaissance work suited Douglas Sampson. The optometrist from Adelaide had joined No. 16 (Army Cooperation) Squadron RAF in Somerset, England in December 1941 as a “bright, alert, self-assured, confident” pilot, fresh from training in Australia and Canada.

Flight Lieutenant Douglas Sampson DFC in December 1944

Operating Westland Lysanders and P-51 Mustangs, Sampson began flying tactical reconnaissance missions and anti-rhubarb patrols (sweeps for low-flying enemy aircraft) along the English coast and across the Channel. The operations did not match the danger of Bomber Command, but they were not without risk.

Sampson had a close call in June 1943. While practicing fighter tactics over Middle Wallop, Flying Officer William “Wendy” Wendelken flew into Sampson’s Mustang. The collision gouged the nose of Sampson’s aircraft, tore apart Wendelken’s left wing, and caused Sampson to belly land at 180 miles per hour. Sampson’s .50 calibre machine-guns bent on impact and his ammunition burst, but both pilots emerged unscathed. Sampson returned to flying duties two days later.

The gouged nose and scraped underbelly of Sampson’s Mustang following his collision with Wendelken in June 1943. (AWM2018.975.54)

In July 1943 No. 16 Squadron was placed under the direction of General Dwight Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), the command responsible for planning the Normandy invasion. Operations ramped up in intensity as Sampson transitioned to Spitfires and flew photographic reconnaissance missions over sites such as Dieppe, Calais and Boulogne.

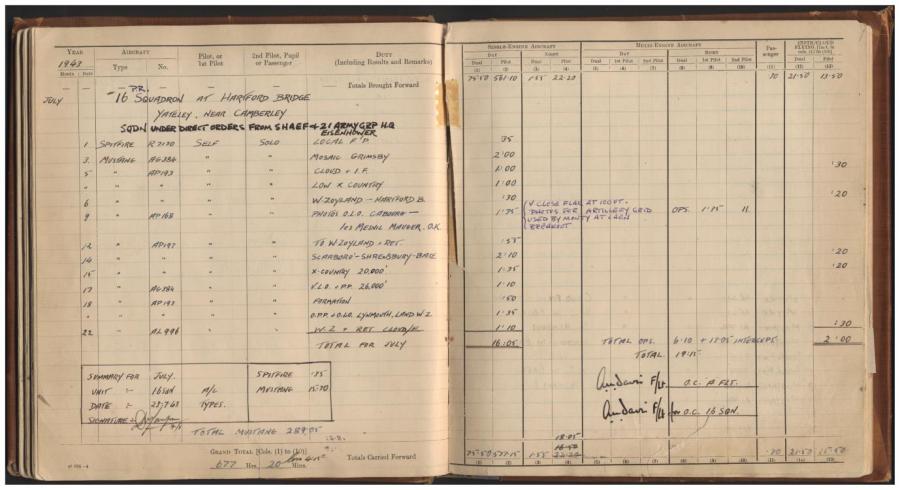

Sampson’s flying logbook records that he observed destroyers in the harbour at La Havre, encountered close flak near Cabourg, and photographed an artillery grid at Caen. He later wrote that his photographs of the artillery grid were “used by Monty [General Sir Bernard Montgomery] at Caen breakout” in the aftermath of D-Day.

Sampson’s flying logbook, among his private papers held by the Research Centre in AWM2018.975.52, records his flights under SHAEF in July 1943 and the use of his photographs by “Monty”.

Sampson’s most significant mission came on 29 May 1944, when he was tasked with capturing a large-scale image of “Utah”, one of the landing beaches for D-Day. The Spitfire Mk XI was capable of taking reconnaissance photographs from an altitude of 30,000 feet. Utah, however, needed to be captured with a high-altitude camera at low level. To reduce camera blur and enhance focus, a new type of film and a modified camera were developed at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough.

The mission was a success. After almost two hours in the air, Sampson returned to RAF Northolt with clear footage of the beach and the underwater defences at Utah. He later remarked that the photographs were so magnified that “even the prickles on the barbed wire could be clearly seen”.

Sampson’s logbook from June 1944, which includes entries for his D-Day flight and his post-tour celebration in a “PINK!!” Spitfire Mk XI.

Sampson completed the 55th and final operational sortie of his tour on the D-Day flight over Coutances and Saint-Lo. It was a fitting end to his time with No. 16 Squadron. In celebration, he flew an aerobatic routine around Northolt in what he recorded as a “PINK!!” Spitfire Mk XI.

An article published in Melbourne’s Herald a week after D-Day praised the efforts of the photographic reconnaissance pilots. The work of these “camera spies”, the correspondent wrote, enabled Allied commanders to plan for the gradients on the invasion beaches and “made possible Bomber Command’s classic blasting of the Normandy coastal fortifications”: the Germans’ formidable Atlantic Wall. As for Sampson, the correspondent continued, Utah was known among the “fliers” as “Sammy’s beach” since his photographs “enabled the Americans to locate almost every strongpoint”.

Sampson’s medal group, featuring his Distinguished Flying Cross at left (AWM2018.975.16)

In recognition of his skill and success on these reconnaissance missions, Sampson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in October 1944. By the end of the war he was a squadron leader in command of No. 288 Squadron RAF, his own army cooperation unit.

While the airmen in photographic reconnaissance are less well remembered than those who flew in fighters or in Bomber Command, their work was no less important. “Camera spies” such as Douglas Sampson were vital in paving the way for D-Day, for breaching the Atlantic Wall, and for and securing Allied victory in Europe.