Eastermorn Waller - an Australian casualty of the Paris Kanone

In pondering the awful consequences of war, sometimes we can look at the works of Tolkien or Hemingway or countless other authors, scientists, and artists who survived the experience of battle, and think Humanity is lucky that they survived, and were able to later craft their great works. Conversely, we can only guess what creations might have been made, and what heights we might have soared to, if particular individuals had survived.

So it is with Miss Eastermorn Waller.

Eastermorn Waller, The Sun 28 April 1918

The delightfully named Eastermorn was born on 9 April 1882 at Balmain, the proud daughter of one of Sydney’s society families. By the age of 11 she had shown great promise at the violin, studying under Herbert H Rice, and first appearing on the public scene in 1893, playing ‘Airs Bohemiens et Syriens’ by Hubert Léonard at a society concert at the YMCA in Pitt Street, together with other young students. She appeared again in 1896 and 1904, playing variously for the Women’s Branch of the British Empire League, and at the Royal Art Society.

In 1901 she was presented to their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, during their tour of the Empire. Punch magazine noted that she ‘wore a dress of ivory duchesse satin, made with a long court train, the whole being draped with a rose point lace and chiffon, and [she] carried a large white shower bouquet of white roses and tulle. White roses were worn in the hair’.

In 1906 Eastermorn left Australia to take up serious violin study in Italy. By 1911 we find accounts in Australian newspapers noting that she had for some years ‘been studying at Prague under Sevelk and more recently with Suchy and was now creditied with making successful appearances in Vienna. She had adopted the stage name of Mlle Vivia de Varennes and hoped to commence on a tour of Europe before long.’

At the time war was declared, Eastermorn was studying in Germany, and found herself trapped there for nearly two years. Two years later she contrived to get to Paris, where she remained, taking up the study of violin and performing as ‘first violin’ in a prominent orchestra. But it is there that the talented violinist was struck down, in Spring of 1918.

For several months, from March 23rd 1918, Paris had endured a seemingly random series of explosions. At first, it was thought to be the result of bombs dropped from high flying aircraft, or the work of saboteurs. Within a matter of days however, ballistics experts determined that instead, Paris had been targeted by very long range artillery.

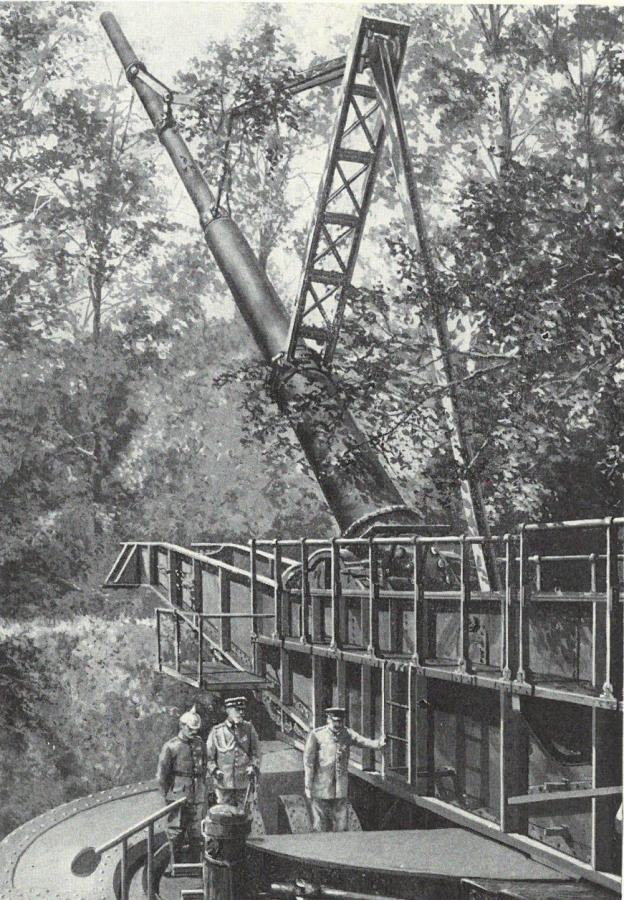

The type of weapon that fired the shells was extraordinary. Until its advent, the maximum range achievable for any artillery shell was 62 km. The guns that fired on Paris, however, were capable of hitting targets at a range of 126 kms, and were therefore able to keep well-hidden and out of harm’s way. Termed by the Germans the Wilhelm-Geschütze, they later also became known as the Paris-Kanones. Seven guns were built, using as their basis a 35 cm SK L/45 gun, into the barrel of which was inserted a sub calibre 21 cm barrel.

The gun and carriage in position

An enormous amount of research and development went into the design, with factors such as the density of the atmosphere, the rotation of the earth during shell travel, air temperature and wind force all having to be considered. Interior ballistics were problematic; the erosion of the barrel with each shot fired meant that each round fired was unique, machined to cope with the wear in the tube, and the amount of charge used for each succeeding shot was also necessarily different.

In total, the seven guns fired 343 rounds at Paris between March and August 1918, killing 256 men women and children and wounding 620. Many of the casualties occurred when one of the shells hit the Church of St Gervais, opposite the Hotel de Ville.

The interior of the Church of St Gervais.

We do not know yet the exact date on which poor Eastermorn was killed. However, the first accounts of her death, at age 36, reached Australia in late April. Popular, talented, and destined for greatness, the nature of her death was shocking to her friends and relatives in Australia, many of whom had already lost loved ones throughout the course of the war.

The Sun Newspaper noted on receiving news of her death that ‘She was father’s beloved girl and the one little grain of comfort is to be found in the fact that he will never know of her death, dying himself a few months since.’ She was however, survived by a brother and three sisters and a number of nephews, one of whom later married the daughter of Sir Edmund Barton.

Eastermorn was perhaps the only Australian female civilian killed directly by enemy action in the First World War, and as was the case with Australia’s military casualties, the world was a poorer place for her absence.