A family united by grief

Private Edgar David Granger, left, and Private Robert Thompson Moore, both of the 55th Battalion. Taken by Louis and Antoinette Thuillier in Vignacourt, France during the period 1916 to 1918. Granger is wearing a Lance Corporal's jacket.

They trained together, served together and died together. But the story of Robert Moore and his best mate Edgar Granger is also a remarkable story of love and friendship that would unite two families during the First World War and help solve a mystery 100 years later.

The pair first met while training at Cootamundra and Goulburn in country New South Wales in 1916 and went on to serve as stretcher bearers together on the Western Front in northern France.

Like thousands of Allied soldiers, Private Edgar Granger and Private Robert Moore passed through the small French village of Vignacourt near the Somme battlefields. It was there that French couple Louis and Antoinette Thuillier photographed thousands of troops, including more than 800 Australians.

Considered one of the most precious visual records reflecting the service and sacrifice of Australian soldiers in the First World War, their collection of iconic glass-plate negatives was discovered in 2011 after lying undisturbed for nearly a century in the attic of a farmhouse in Vignacourt.

The Chairman of the Australian War Memorial’s Council, Kerry Stokes, acquired the fragile plates, 800 of which were donated to the Memorial in 2012.

Since then, the Memorial has been working to identify the men pictured in the images who feature in a special exhibition called Remember Me: the lost diggers of Vignacourt, which is currently on a national tour.

One of those images is of Private Edgar Granger and Private Robert Moore of the 55th Battalion. It would be one of the last photographs taken of the pair. They were among a party of stretcher bearers who were killed on 2 September 1918 at Peronne, just weeks before the end of the war. The four stretcher bearers, all hit by the same shell, were buried next to each other in a cemetery in northern France. Edgar and Robert are buried just one grave apart, but their friendship would have a lasting legacy which would endure through the generations.

Robert Moore. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

United in grief at the loss of their beloved sons, their mothers began writing to each other, and a bond soon developed between the two families.

When Robert’s eldest brother, John, visited the Granger family farm at Collector to pay his respects, he met and fell in love with Edgar’s eldest sister, Katurah. They married in February 1923 and named their first child, Edgar Robert, in memory of their two brothers.

Edgar’s youngest sister, Myrtle, was bridesmaid at their wedding, and Robert’s youngest brother, Frank, was best man. Although Myrtle was said to have been engaged to another man at the time, they too fell in love, and were wed in September 1926. Edgar’s two sisters had married Robert’s two brothers, and the Granger and Moore families had become one.

A century later, Robert and Edgar’s great-niece Ondrae Campbell began to learn more about her remarkable family history and went on a journey of discovery that would take her to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and the “Lost Diggers of Vignacourt”.

“It all started when our mother received a phone call from one of her friends,” Campbell said.

“They were all farming people out in the south-west between Hay and Hillston and her friend was clearing out her auntie’s house on a farm when she’d found a box of letters tied up with pink ribbon in the garage covered in dust. She opened them up and realised … they were from mum’s uncle Robert who had lived on the farm next door.”

Years later, Campbell began transcribing the letters so that they would be easier for her mother to read.

“My mother and her family had always known that their mother and her sister had married their father and his brother; and that one family were the brothers of Robert Moore, and the other family were the sisters of Edgar Granger from Collector. But their parents never talked about it because they had lost their brothers, and my mother didn’t really know the story, so it was always a bit of a mystery to my mother until we typed up these letters, and then she began to join the dots,” Campbell said.

“Of course, once you start trying to read them and type them, you get a lot of questions, and when I went around asking questions of aunties and uncles and so forth, what I discovered was that this one person – a young man who never married, never had any children, never did anything other than farming, and never went anywhere until he joined the army and went to the war – had left behind this incredible amount of information [that] had been dispersed between family members. And when you put it all together and find out what it means, it’s an amazing story.”

John and Katurah Moore on their wedding day. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

Frank and Myrtle on their wedding day in 1926. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

She wrote a blog using the letters Robert had written to his family and to his neighbour, Carrie McDonald. “I never even knew half this stuff was kicking around until I started asking people,” Ondrae said. “It’s just amazing what’s in people’s bottom trunk, or behind the shed door, and hasn’t been looked at for 100 years … but from his letters he was obviously quite keen on Carrie and would have married her if he’d survived the war.”

He jokes that they “captured every hill around Goulburn” during training, and manages to retain his sense of humour despite the horrors of war.

“There’s a hilarious story about rabbits,” Campbell said. “When one of the farmers was eaten out by rabbits, he writes back to Carrie saying: ‘If those rabbits were here we would have had them cleaned up by now.’ In other words, he would have put them in the pot for eating …

“But then we get into 1918 and the letters start to become longer and a bit more in-depth … He talks in one letter about the concussion from a pillbox being blown up and how it deafened him and he had blood coming out of his ears for a while.

“Then after Villers-Bretonneux, he writes a very long letter … He had lost one of his closest friends and I searched and searched to see if I could find out the name of the friend, but I could never nail it…

“The letters get longer as the years go by – they become more profound and I think he sensed that, while there had been horrendous losses, they were starting to get onto the winning curve … But then you get a change of handwriting because that’s the last letter that he wrote, the 3rd and 4th of June, some eight weeks after Villers-Bretonneux.”

Robert Moore's medals were given to his mother. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

The next letter was written by Carrie’s brother Alex McDonald, who wrote from Peronne to tell her of Robert’s death. She never married, and treasured Robert’s letters for the rest of her life.

It was these letters that led to Campbell’s blog, which she posted on the internet with the only photograph the family had of Robert and Edgar together. When a member of the public saw the photograph on the internet, they knew immediately it was from the Thuillier Collection of glass plate negatives, which were taken in Vignacourt between 1916 and 1918.

Recognising the Vignacourt backdrop in the photo that Ondrae Campbell had used in her blog, a member of the public contacted the Photo, Film and Sound team at the Memorial.

Curator Joanne Smedley then met with the family, who were able to show staff the original photograph and help officially identify the men, taking the total number of men identified in the negatives so far to 165.

“I was able to confirm that this was one of our Vignacourt negatives that we had been hunting for,” Smedley said. “Robert Moore and Edgar Granger were from a unit that we hadn’t associated with Vignacourt before, but when I went back to the war diary and had a look, I found that their camp was only about six kilometres away, so it was quite feasible that they could have gone there, and the ultimate evidence, of course, is having the original print photograph that was taken in Vignacourt.

“Now, thanks to Ondrae Campbell and the member of the public who contacted the Memorial, we have two more names and a really powerful story about two men who became friends and were killed by the same shell.”

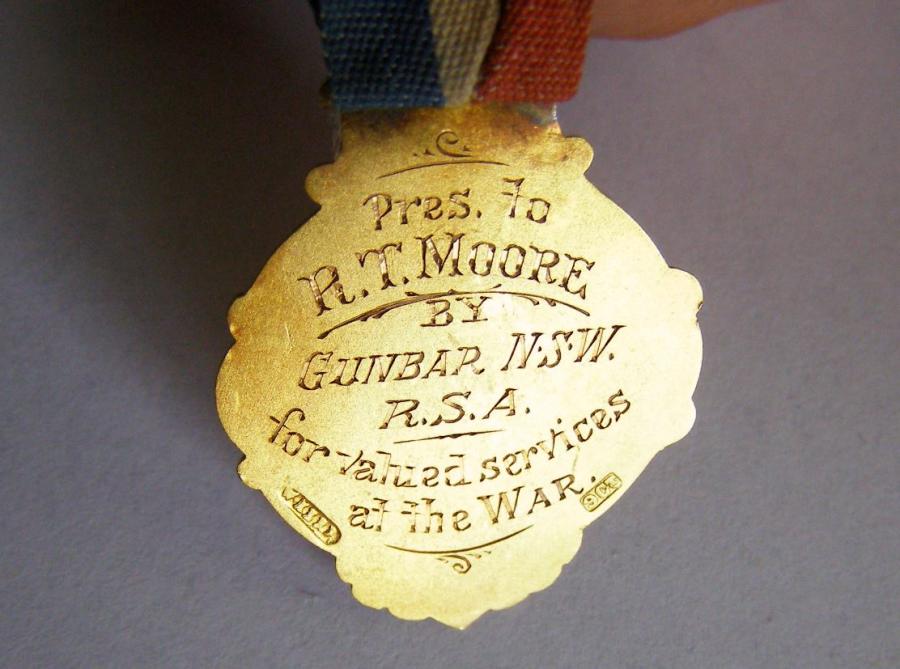

This medal was presented to Robert Moore's mother by the people of Gunbar. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

This medal was presented to Robert Moore's mother by the people of Gunbar. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

For Ondrae Campbell and her family, the Vignacourt photograph of Edgar Granger and Robert Moore is special for another reason.

“That’s the only photo we have that proves the story that they were mates,” Campbell said. “And for me, this concept of friendship is what it was all about. The two mothers wrote to each other reflecting on their grief about the loss of their two sons … and it’s this whole story of togetherness.”

Campbell has since visited their graves in France, and the extended family gathered at the Memorial on the 100th anniversary of their deaths for a small wreath laying ceremony in honour of their service and their friendship.

During her research, she found a card in her grandmother’s collection of treasured possessions that summed it up beautifully: “The treasures of life are many, but friendship’s the greatest of any.”

“I’d never heard that saying before,” Campbell said. “But Robert and Edgar were friends … and the two families, no matter how far apart they get, have always been friends.”

Remember Me: The Lost Diggers of Vignacourt touring exhibition is on at Hervey Bay Regional Gallery until 11 November 2018.

If you think you have identified a relative in one of the photographs in the Vignacourt collection, please contact the Memorial’s curators at photofilmsound@awm.gov.au

The friendship card that Frank sent to Myrtle sums up the relationship between the two families that has continued down through the generations. Photo: Courtesy Ondrae Campbell

Nieces and nephews at the wreath laying ceremony at the Memorial on 2 September.