Remembering the Walker brothers

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people. It also contains examples of racist and offensive language that were used at the time.

Private Edward Walker was one of the soldiers pictured in The Queenslander Pictorial supplement to The Queenslander, 1917. Image: Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

Edward Walker had recently returned home from Europe when he entered the Federal Hotel in Casino to enjoy a pint of beer with his mates after the end of the First World War.

He had been seriously wounded in northern France, and had lost his brother in the fighting on the Western Front – but instead of being welcomed home as a hero, Edward became the subject of a local court case when a policeman spotted him drinking at the bar with two of his friends.

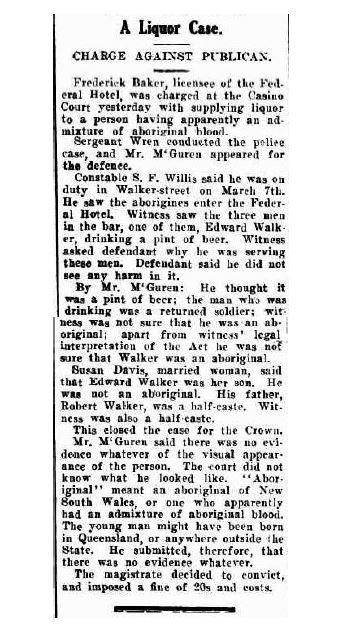

He was arrested for drinking alcohol, and the publican who served him was charged and later fined for supplying liquor to an Aboriginal.

In his defence, the press reported that the publican argued: “He did not see any harm in it ... the man who was drinking was a returned soldier ... Walker, who had purchased the liquor, had gone away to fight for them and was entitled to all they could give him ... He thought it should be possible for this man to have a glass of beer if he wanted it.”

Edward was one of three brothers who enlisted or attempted to enlist during the First World War, despite restrictions preventing Indigenous Australians from doing so.

Today, his British War medal is part of the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial.

Edward Walker's British War Medal is now part of the collection at the Memorial.

For Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial, it’s particularly special.

“Objects like these are reasonably rare,” Bell said.

“We’ve got just over 850 Aboriginal men who were awarded medals in the First World War, so to be able to have this object in the collection is particularly significant for us.

“Through this object, we can tell Edward’s story and bring that story to life.”

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell has been researching the military service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent, and is working to identify Indigenous Australians who have served or are currently serving.

He said Edward’s story was a powerful reminder of the restrictions Aboriginal people faced during and after the war.

A Yuin man from the South Coast of New South Wales, Edward Walker was born in Kiama in October 1893, the son of Susan Robinson (later Davis) and Robert Walker. He was working as a horse breaker near Lismore when he decided to follow in his brothers’ footsteps and enlist in July 1917.

The 1903 Defence Act, which was amended in 1909, had exempted people who were not “substantially of European origin or descent” from enlisting. But in 1917, after the first conscription referendum was defeated, and with large numbers of Australian casualties in Europe and the need for more manpower due to the ongoing war of attrition in the trenches of the Western Front, Military Order 200 was issued. It stated “half-caste” Aboriginal men could enlist in the AIF, provided the examining medical officers were satisfied one of the parents was of European origin. All previous instructions on the subject were to be cancelled.

Edward’s older brother Thomas had managed to enlist in September 1916 despite the restrictions that were in place, and was already serving on the Western Front. His brother Robert had then volunteered in June 1917, after Military Order 200 came in, and had been allocated to the No 1. Depot Company on 11 July 1917, but was discharged as “medically unfit” for further service that same day.

Edward's brother Thomas was killed during a German bombing raid near Bayonvillers in 1918. He was also one of the soldiers pictured in The Queenslander Pictorial. Image: Courtesy State Library of Queensland

Edward however was successful. Assigned to reinforcements for the 49th Battalion, he embarked for overseas service aboard HMAT Medic in August 1917 along with a number of other Aboriginal men from Queensland.

After further training in England, Edward proceeded to France, where he was re-mustered into the 25th Battalion. He joined the unit in the field in January 1918 at Neuve Eglise, where he would have been pleased to learn that his brother Tom was serving in the same battalion, albeit in a different company.

When Edward was wounded in action during the fighting in July 1918, he was evacuated to England for treatment at the Southern General Hospital in Plymouth. Six weeks later, he wrote to the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Bureau from Weymouth to enquire about the fate of his brother. Tom had been killed-in-action on 11 August 1918 while the battalion was in the forward area near Bayonvillers.

A Private Ernest Avard, from the same unit, was able to reveal that he and Tom had been in the same trench when a low-flying German aircraft had dropped a bomb directly onto their trench, killing Tom outright and burying Avard alive. Avard was lucky to escape, and Tom was buried the next day. A Lieutenant Batten had placed a cross on Tom’s grave at the cemetery at Bayonvillers.

Tom left behind his wife Lily and their two young children, Edward and Jean. Lily was living with their family on the Aboriginal reserve at Ulgundahi Island on the Clarence River when she learned of her husband's death. The island had been set aside by the Aborigines Protection Board in 1904 as a reserve for displaced Aboriginals as more and more of their traditional lands disappeared when they became European settlements. Tom’s remains would be reinterred at Heath Cemetery, Harbonnières, after the war.

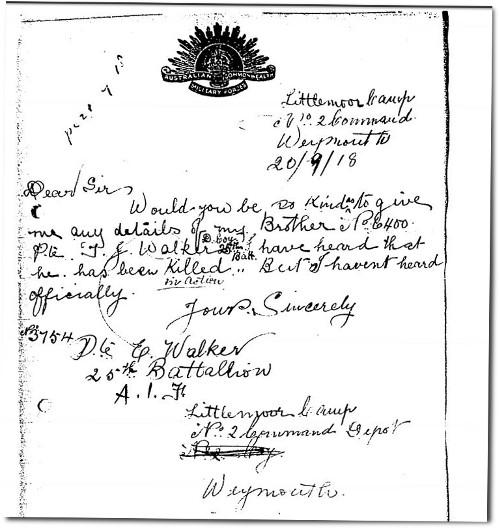

Edward wrote to the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Bureau to make enquiries about his brother Thomas after he had heard that he had been killed.

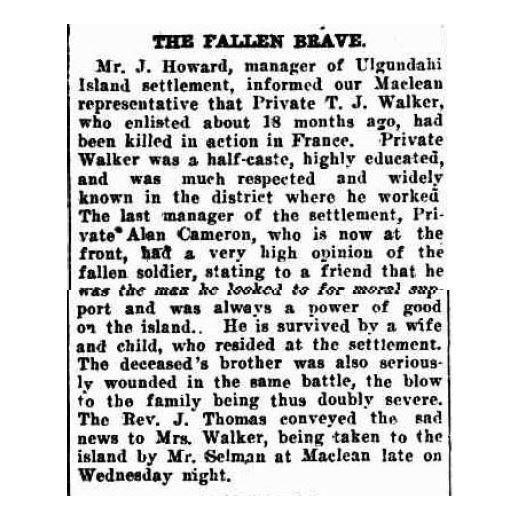

Thomas's death was reported on in the Daily Examiner in Grafton on 30 August 1918.

Shortly after his brother’s death, Edward, while on leave in October 1918, contracted a mysterious new form of influenza that had begun to sweep around the globe. The pandemic that followed would become more deadly than “the war to end all wars”.

In a little over a year, it infected as much as a third of the world’s population, and killed as many as 100 million people. The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918–19, as it became known, would become one of the most deadly pandemics in human history.

Edward was one of the lucky ones. He survived, but was deemed no longer fit for active service, and with the Armistice imminent, was slated to return to Australia. He was repatriated home aboard the troopship HMAT Bakara, leaving England in December 1918, just a month after the Armistice was signed.

Edward joined his family on the Aboriginal reserve at Ulgundahi Island in 1919. He went on to marry and worked in the area until his death in 1976 at the age of 82.

Today, Edward and his brothers are among the 1,100 Indigenous Australians known to have enlisted or attempted to enlist during the First World War.

Bell would love to learn more about them.

The Casino and Kyogle Courier and North Coast Advertiser, 22 March 1919.

“We don’t know what was in Edward’s mind when he went to enlist, or much about what happened to him after he came home,” Bell said.

“We never had the opportunity to ask Edward or his descendants why he volunteered, but we can presume he wanted to perform his patriotic duties, to be treated equally, to earn an equal wage, and to possibly use his service in the AIF as a pathway to citizenship and recognition.

“It appears he settled back into his community in and around the Kempsey/Casino area after the war, and that’s where we find this incident where he was charged with drinking alcohol.

“It was illegal for Aboriginal people to consume alcohol at that time, and so we’ve got the reference to him being arrested for drinking in a pub. It’s a reflection of how poorly our Aboriginal veterans were treated in society after they returned.

“Having been equal in service, Edward comes home and can’t even go and have a beer in a pub. It’s seen as the quintessential Australian right to be able to go in and have a beer in a pub – and here’s a veteran from the First World War who was willing to go and fight for his country who comes home and is treated unequally.

“But the highlight of the story for me is that the publican stood up for him and recognised his service. He makes that statement where he effectively says, ‘He fought for us. He deserves a beer if he wants.’ And that is very significant.

“At that time, the publican would have also been risking his licence, because he was also charged with providing alcohol to an Aboriginal person, but he saw it as the right thing to do.

“Having Edward’s medal in the collection now allows us to dig further and share not only Edward’s story, but also that of his brothers.

“Through this one medal, we’ve now got the story of three brothers who all volunteered, but had three very different outcomes.

“It reflects the different treatment individuals experienced during the First World War. One brother gets in with no problems and goes overseas and makes the ultimate sacrifice. One bother gets in and goes overseas and returns, but is then treated unequally in society. The other brother gets in, and is then rejected the same day because of his race.

“They’re three brothers, all from the same family, but with three very different outcomes.”

He has appealed for anyone who knows more, or knows where Edward’s Victory Medal is, to get in contact.

“If they are your family, or if anyone has further details about any of the brothers, please let me know,” Bell said.

“It’s about putting an Indigenous face on the Anzac legend and dispelling the myth that Aboriginal people didn’t defend Australia, and didn’t go to fight.

“We’re trying to encourage people to come forward and tell their stories … to help us tell the broader story of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experience.

“Because no-one saw them, perception of their service was skewed, and for a long time it appeared as if they had never existed.

“It’s a little known story that deserves to be widely known.”

Michael Bell is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au