A lucky escape

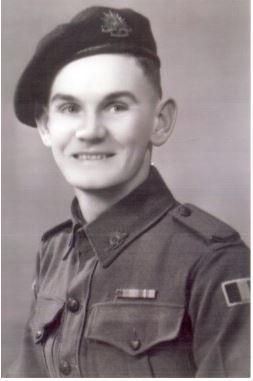

Eric Geldard: "I just carried on, and accepted what had to be accepted, and did the best I could."

It was a moment that changed Eric Geldard’s life forever. At 4 o’clock on 26 July 1945, he was accidently shot through both legs in New Guinea and almost bled to death as he was carried to safety on a makeshift stretcher for seven hours through enemy territory by “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels”.

“I was running out of blood, and that was what was going to kill me,” he said simply. “I don’t think I was really scared. I just took it as, well, that’s what happens if you go to war, I suppose. No, the worst part was after.”

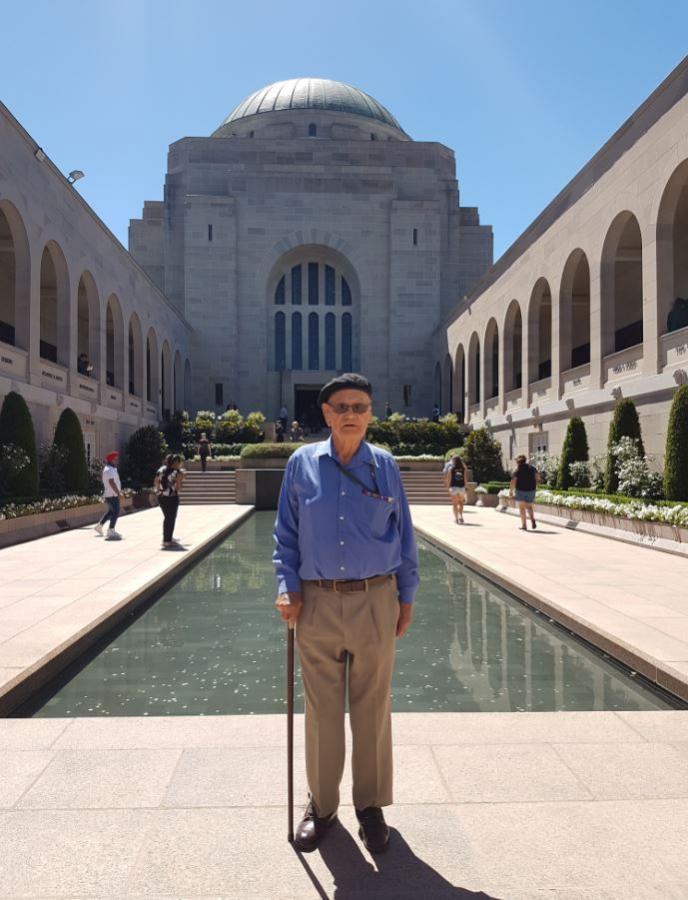

Geldard, now 93, shared his story while visiting the Australian War Memorial in Canberra to remember his mates and pay his respects. He was just a teenager when the war broke out, but his uncles had served during the First World War and he was determined to do his bit.

“My parents were graziers with a sheep and cattle property, and I was exempt from military training, but things got desperate and they called for members to the Volunteer Defence Corps,” Geldard said. “The remarkable thing about it was that the day I turned 18, I was sworn into the army – part-time VDC – and [was] issued with a rifle and live ammunition the very first day.”

When the RAAF called for volunteers from “any walk of life”, he signed up and began training as a wireless air gunner. “They’d take you from the railway, from off the land, from anywhere at all,” he said. “And I answered that call. When the invasion of Europe took place, they didn’t have the losses they expected, so we became redundant.”

It was then that he and a few mates saw some “army blokes” parachuting into the airfield, and decided to ask them a few questions. They turned out to be commandos, and Geldard decided to become one of them. He and his mates transferred from the air force to the army, and volunteered for the commandos at Maryborough.

“My dad was battling away at home in his 60s trying to run four properties without any permanent help and I felt, ‘I better do the best I can while I’m here,’” he said. “I looked on it very personally. To me, I liked where I was, I liked the people, and I felt they needed protecting … [so] we just went out to fight to protect our home.”

After completing jungle warfare school at Canungra, Geldard was sent to Wewak in New Guinea with the 6th Division Cavalry Commando Regiment and joined the 2/9th Commando Squadron. It was while serving as a commando during the Aitape-Wewak campaign that he was accidently shot by a mate just weeks before the war ended. He was just 20 years old at the time.

“In that area there was a coastal plain about a kilometre wide and then from there it just went up. It was so steep that there were just native foot tracks … and in places there were steps cut in everywhere,” Geldard said.

“My unit was manning an outpost there and the Japanese had all that country and everything. There was a whole army of them – 24,400 came in when they surrendered – and there was a whole 30 of us.

“The day that I came to grief there were 14 of us who had been out patrolling in that area. We had tried to see where the enemy were because we had no helicopters in those days and fixed-wing aircraft couldn’t see through the canopy [of trees].

“Where we had to walk was along the crest of the razor back ridges. [They were] about the width of a tennis court, and then it just went down … on either side. [It was] a bit hazardous walking along there because we couldn’t see more than perhaps a metre either side of us for all the big leaves on the plants. And we also couldn’t see much in front of us either, perhaps about 20 metres.

“We did that all day, and then got back to the outpost. When we were cleaning our weapons, we had a little makeshift two-man shelter. It was only made up with a couple of groundsheets stuck together and my mate had an Owen gun – the Mark 1 – before they put the safety catch on …

“He was cleaning his Owen gun, as you had to do when you finish a patrol, [and was] making sure it was full of ammo.

“He had it … and he moved it across [his body] and the cocking lever caught in his shirt … It fired and the bullet went through both my legs.

“I had a sort of a bunk I was sitting on in a two-man shelter and it was very painful. It felt as if somebody had hit the funny bone with a sledge hammer, and I thought, ‘Well, there’s no signs of any broken bones, I’ve got out of this pretty well,’ and then I started to see blood going everywhere, and I knew I was in trouble then.”

Eric Geldard: "I felt, ‘I better do the best I can while I’m here."

It was more than 70 years ago, but it’s a day he will never forget. “Bit unfortunate, wasn’t it?” he said with a laugh. “Well, the problem was the bullet cut the main artery, the femoral artery, and also two thirds of the sciatic nerve, so I was virtually bleeding to death, and the only way to help me … was to carry me.

“All the hospital and casualty [facilities] were way down on the coast, so we had to get down about 4,000 feet on a narrow track just like they show you on the TV at Anzac Day. It was the same thing, me on a stretcher, and about eight Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels carrying me.”

He was drifting in and out of consciousness as they made their way through enemy territory, and remains forever grateful to the men who carried him to safety that day. Fifty years later he was able to thank Raphael Oimbari, who was invited to Townsville to represent the people of New Guinea who helped Australian soldiers during the war.

“Oh, they were good,” Geldard said. “Gee they were good. They were only little fellows, about five foot three or four, and their job was to carry up provisions to the outpost up where we were.

“They happened to be there, and … it was only a makeshift stretcher too, but they carried me 4,000 foot down the narrow trail. In places there were 30 or 40 steps in the trail, and they were so considerate. Sometimes some of them would get down with their hands up and pass the stretcher across the top …

“One of the blokes there kept saying, ‘Eric, for Christ’s sake keep conscious,’ because we were still in enemy territory, and if they thought, poor bugger, I’m finished, well they would just drop me and go …

“Eventually, it took seven hours to get me to the casualty clearing station … and I was fresh out of blood ... But it got worse later. The sciatic nerve didn’t like getting shot through, and every two minutes it would go ‘rammm’ down the leg, and it did that for 16 days and nights, and I was on maximum morphine all the time.”

He was flown to Brisbane and spent 15 months in hospital before returning home to his family in Miles in the Western Downs region of Queensland. It was while waiting at Roma Street Railway station in Brisbane that he met his future wife Betty, who had served as an anti-aircraft gunner and search light operator in Western Australia.

“I’d known her as a child, but then we were apart for a long, long time, and then during the war, we accidently met up,” he said.

“There was a long queue waiting to get tickets … and who should I see there in the queue in uniform, but Betty. I said, ‘I don’t know if I’m going to get on this train because it’s taking so long.’ And, anyway, she out and walked up to the front, and said, ‘Well there’s a disabled digger down here,’ and they put me to the head of the queue, so I got home. I was still on crutches … [but] I just kept on keeping on, and we managed to build a house between us, and I’ve spent my whole life in that area.

“My dad helped me go on the land, which I’d always wanted to, so I finished up pioneering the property and it’s still in the family. It was largely unimproved – there was no house, there was not much water, a little dam, and it was good agricultural country, but I had to clear the timber off it, and then I made a very happy marriage and had four wonderful children.”

Eric Geldard: "I just carried on, and accepted what had to be accepted, and did the best I could."

Today, Geldard still runs his own property and remains an active member of his local RSL sub branch. He was instrumental in helping to establish a war museum in Miles and, with the help of the town’s historical society, managed to find photos of every one of the 100 local men and women who enlisted during the war.

“There was one we didn’t get, but we got his grave. He was buried in Palestine, but otherwise we got all the local boys and girls who went off to war, and I’m a bit proud of that,” he said. “I look at those photos, and we’ve got them all in the same size frame, and you know I think I know every single one of them …”

He still considers himself lucky to have survived the war. But when asked if he was frightened that he wouldn’t make it home, he says simply: “War can do that.”

“You didn’t know who was there, or there, or in front,” he said of his time serving in New Guinea. “But I bolstered myself up a bit by thinking of my uncle [Herbert Geldard] who had been wounded twice in World War I. Everybody above him was killed, and as a corporal he took charge and was commissioned in the field and given a Military Cross … [My uncle Bill], he’d been rejected twice as medically unfit and the third time they took him and he got blown up at Fromelle ... I thought, ‘Well, if Herb and Bill can do it, I’d better do the best I can.’”

But Geldard never got to see the mate who accidently shot him again. “He was probably the last Australian soldier to be officially killed in action three days after the war ended,” he said quietly. “He was an only child and he was only 19. I met him when we joined the air force together … [and] he had to stay there and keep fighting. I just made sure everyone knew it was an accident.”

For Geldard, it was important to visit the Memorial to see his mate’s name on the Roll of Honour and pay his respects. “War is a terrible thing,” he said quietly. “It always has been. It’s a shocking thing. One of the worst things that can happen, but I don’t know of an alternative. I just don’t know of an alternative. What do you do? Just lie down like a dog and get run over or do you stand up and fight? And that was what we did. My generation saw fit to stand up and fight.

“I’ve been very fortunate indeed … and I’ve had a good productive life ever since.

“I feel it’s important for Australians as a whole and particularly the children to know the history of what happened and why it happened.

“When I was walking through that scrub I was thinking of my two uncles who had done their bit. I think I just carried on, and accepted what had to be accepted, and did the best I could.

“But the thing that I’ve always been pretty sad about is that although I tried so hard to do what I could in the war, I don’t think anything I did had any affect whatever… I think my part was very little, but I meant well, I really did.”