'It’s pretty inspiring'

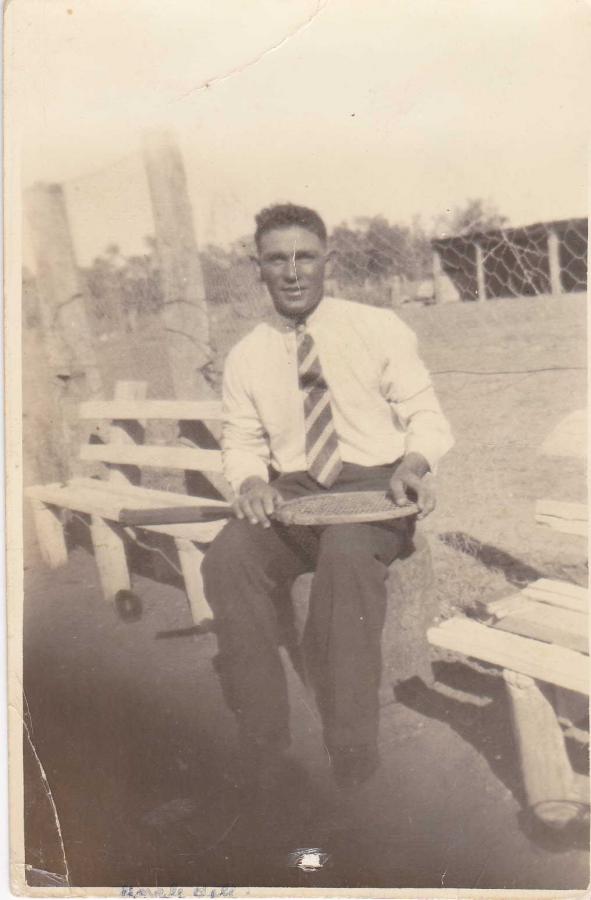

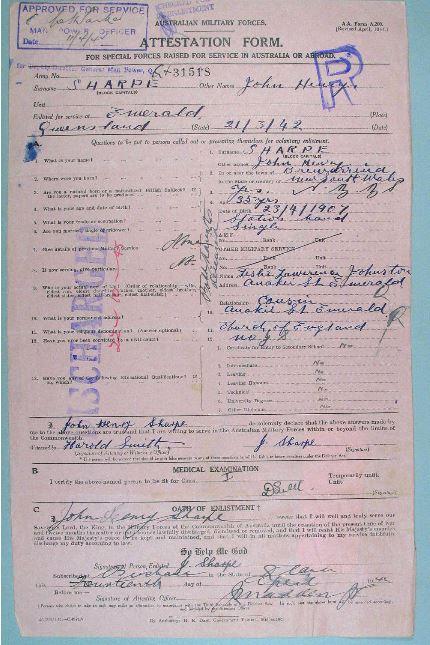

Erin Vink’s great-uncle John Henry Sharpe was a remarkable man. He enlisted for service in the Second World War at Emerald, Queensland, in 1942 at the age of 35, but he had a secret.

“That’s not actually the name his family knew him by,” Erin said.

“His name was William Hanson or Davis – he used both – and he grew up on the Aboriginal mission in Brewarrina with his sisters, but he went to the pub one night and got into a fight and thought, ‘Oh no, I’ve got to leg it, I’ve got to get out, they’re going to catch me,’ so he moved to Rockhampton and changed his name and started a new family there.

“He enlisted during the Second World War and went to Tobruk as a reinforcement after the siege. He was also in North Africa at El Alamein and went to New Guinea and Borneo for a little bit as well, but he was lucky; he came back in one piece.”

For Erin, a proud Ngiyampaa woman, it’s important to share the stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander servicemen and servicewomen who gave so much for their country.

“We have these really amazing stories of Aboriginal people being heroes,” she said.

“It’s pretty incredible and it’s pretty inspiring; to think that some of these people who were going away to war in the First World War and the Second World War would even want to serve their country when it was illegal to do so, their children were being removed, and they were being put on missions, or their family was being murdered within living memory, is pretty amazing. But it just goes to show how important country is to them.”

As the Indigenous art curator at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Erin has been working to help ensure their contribution is never forgotten.

She provides management and support to major Indigenous art, photography, film and sound commissions and acquisitions and has been adding Indigenous languages to the national collection database so that people, places and objects associated with a particular language group can be easily identified and found.

“When I started at the Memorial, we didn’t have any kind of Indigenous cultural protocols, and we didn’t have any way to track language groups or people’s nations or tribes,” she said. “It was a real privilege to get the job, so it was important to get it right, and to get the languages up and then create Indigenous protocols for the collection as well.”

Indigenous art curator Erin Vink. Photo: Grace Ephraums

Erin had worked as research coordinator for the family history unit at AIATSIS – the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies – and knew the importance of Indigenous languages and their role in linking communities. She requested a list of Indigenous language groups from linguists at AIATSIS so that items in the national collection could be linked to particular language groups and be more easily identified.

“Within our communities our language is the most important thing,” Erin said.

“There’s been a revival of the importance of language as more and more people are realising that our languages weren’t forgotten, they were taken away from us, so now we are trying to reclaim our languages and our objects.

“It took about nine months, almost a year, to get all the languages into the system and then I re-catalogued the entire art collection, so that every single piece of art that relates to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait islander person is now linked to a language group.

“If you are searching for your family history and you want to see what your people have contributed to the war or to the national collection, you can search your language and see your people and their objects represented.

“It’s really exciting, not just for me, but for others as well; people can now find their people, and that can be a really hard thing to do, especially if you don’t know a lot about your family history.

“Personally, I’ve always known about my family history. It was always really open in my family, but I didn’t grow up on Country, and I don’t speak my language, so if you are trying to reclaim your history, it’s exciting that you have the capacity to do that now.”

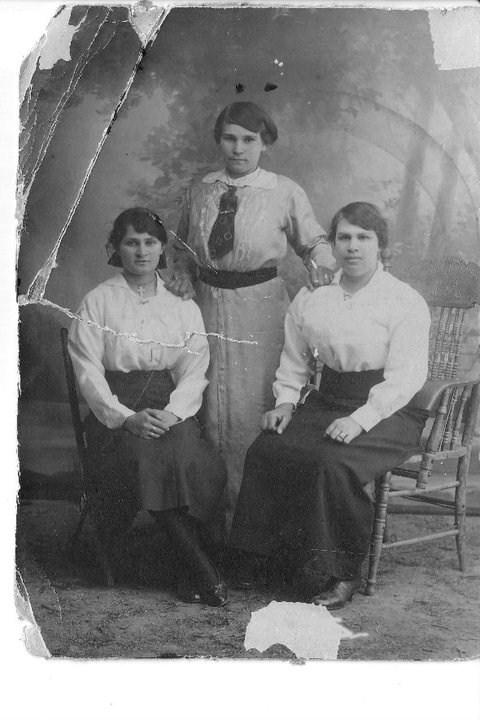

Erin’s great-grandmother Mary Jane Davis, pictured with her sisters.

Erin’s great-grandmother Mary Jane Davis was born in Brewarrina and grew up on the Aboriginal Mission there as a child.

“She was born on the banks of the Barwon River and was one of four children,” Erin said.

“Since then my family has lived on Kaurna Country in Adelaide and here in Canberra on Ngunnawal and Ngambri Country, but a lot of people like me haven’t grown up on Country and have no idea of what their language is.”

For Erin, it’s important to help people reconnect with their heritage and learn more about their culture.

At the Memorial, she has also been working on the introduction of Indigenous cultural protocols for the handling, storage and management of Indigenous cultural material within the national collection.

“It’s been really interesting,” she said. “People often don’t realise the amount of Aboriginal material we’ve got at the Memorial, so it’s been really fascinating to work on.

“When Aboriginal people want to reclaim their culture it’s not a matter of them demanding that everything is done their way or that it’s returned to their Country, it’s more about working with the Community and having their stories told their way.

“It’s about looking at these collections and making sure that they are culturally safe for myself or any other Indigenous person employed at the Memorial to work on it.

“That included archiving racialised language, cataloguing it, so if it was men’s business or women’s business, and ensuring that when it was catalogued and digitised only the appropriate people would be viewing and handling the material, but it was also about making that collection safe for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people who would be coming in to access that material in person or through the digitised records.

“When you are working on it every day, you don’t always realise the scale of it, or the importance it will have in the future, but when you have community come into the Memorial and they ask if we have anything that’s by Pitjantjatjara artists and you can take them down to the Reading Room and you can type Pitjantjatjara into the system and you can pull up all of the artworks, photos and records relating to the people who came from South Australia, it’s pretty rewarding, and you can see community actually benefitting.”