'The day we lost you dad, was the saddest of them all'

Ernest Harrison was killed on board HMAS Canberra when it was torpedoed and sunk during the battle of Savo Island. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

When Andy Harrison was a child growing up in Sydney, there was a painting of a ship hanging on the wall of his family home.

The picture was of the heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra breaking through the waves as it led the Australian Squadron off Wilson’s Promontory in Victoria.

It has been a part of his life for as long as he can remember, but it wasn’t until he was older that he understood its significance.

His grandfather, Electrical Artificer 1st Class Ernest Harrison, was killed on board Canberra when it was torpedoed and sunk during the battle of Savo Island in August 1942.

This print of a painting of HMAS Canberra by John Allcot stills hangs on the wall of the Harrison family home. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

“It was a big shock,” Andy said.

“And it must have been just devastating for the family.

“My father was only ten, and his sister Patricia was only 12.

“There was a telegram, so it would have just been a knock on the door, but of course, when it happened, it hit the newspapers very quickly.

“I grew up in the family home that Ernest and [my grandmother] Dorothy built in Simla Road.

Ernest and Dorothy with their children Patricia and Alan. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

“There were never any pictures [of Ernest] – we had to dig to find them – but there was always this one very old and battle-scarred picture of Canberra on the wall.

“I don’t know where it came from, but it was initially in the lounge room.

“Nobody ever talked about it, and it was never discussed, but it was always there…

“It’s just a print of someone’s painting of Canberra … but my grandmother and my parents kept it, and we’ve now got it hanging up in our place as a reminder.

“You can tell it’s been around for a while, but obviously they still treasured the memory of my grandfather’s service on the ship.”

Ernest with his children Patricia and Alan. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

Andy’s grandfather, Ernest Harrison, was born in Sunderland, England, in the early 1900s, the second son of Granville Harrison and his wife Mary.

In 1920, Ernest immigrated to Australia with his mother and his older brother, Oswald.

Having some experience as a fitter, Ernest enlisted in the Royal Australian Navy in 1924, and trained as an electrical artificer, working on the electrical maintenance of generators and engines.

By the time war broke out in September 1939, Ernest was an experienced sailor with multiple good conduct badges, and a father of two. He had married Dorothy May Matthews at Drummoyne in Sydney in 1927, before the birth of a daughter, Patricia, in 1929, and a son, Alan, in 1931.

Ernest with his daughter Patricia and son Alan. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

He was serving on the HMAS Canberra when it came under attack from seven Japanese cruisers and a destroyer while supporting US Marines in the Pacific on 9 August 1942.

Canberra had been patrolling between Savo Island and the north-western tip of Guadalcanal, along with other US Navy ships when flares lit up the darkness just before 2 am.

Stoker John Oliver Rosynski described the Japanese ships approaching Canberra and the chaos that ensued, recounting how the captain stood on the bridge, slowly and calmly giving orders.

“It seems some power, some unknown devil steered the old ‘Canberra’ through thick and thin for nearly three years, then it let us have it all at once,” Rosynski later wrote. “She never had a chance.”

As the lead ship, Canberra received the full force of the Japanese barrage.

The ship was hit 24 times in less than two minutes, and 84 of her crew were killed, including Captain Frank E. Getting, who was mortally wounded and died later.

Both forces launched torpedoes during the attack, but the Japanese were first to engage with their big guns.

Canberra, having lost all power, was helpless to respond. She was struck by 24 heavy shells, turning her into a listing, blazing wreck, full of wounded and dying men.

August 1942: HMAS Canberra sinking following the battle of Savo Island. Photograph: Ordnance Artificer J.A. Daley, one of the survivors.

“It was hit with massive [enemy] fire and a torpedo,” Andy said.

“And [my grandfather] would have been down in the engine room which copped the brunt of it.

“It lost power straight away and the guns couldn’t move and the firefighting systems didn’t work.

“So there wouldn’t have been much they could do.”

Below decks, as enemy shells exploded, damage control crews vainly fought the fires and the ship’s medical parties were forced to tend to the wounded in the darkness. Insufferable heat caused the sickbay to be evacuated as the order came to prepare to abandon ship and the wounded lay in pouring rain, covered as much as possible by coats and blankets.

“I spoke to the Captain but he refused any attention at all,” the surgeon later wrote. “He told me to look after the others.”

Ernest, pictured on Canberra. Image: Courtesy the Harrison family

In the darkness and confusion, the attacking force wreaked havoc, the Japanese pressing home their advantage, sinking three additional American cruisers before making good their escape.

Canberra was still afloat in the morning, but was beyond repair. She was deemed unsalvageable and scuttled into the stretch of water now known as Ironbottom Sound.

USS Selfridge fired 263 5-inch shells and four torpedoes into Canberra, but she refused to sink. Eventually a torpedo fired by USS Ellet administered the final blow, and Canberra sank at about 8 am on 9 August 1942.

The US Navy Baltimore Class cruiser USS Canberra was later named in her honour, the only American warship named for a foreign warship or a foreign capital city.

Ernest, pictured back row, second from right, with members of Canberra's crew. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

In one night, the Allies had lost four cruisers and suffered the deaths of over 1,000 sailors. Canberra had 84 killed or died of wounds and another 109 wounded from her complement of 819.

Ernest was among those who were killed.

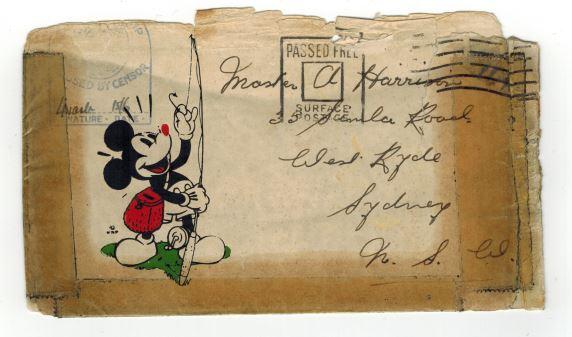

He and his ten-year-old son Alan had been writing letters to each other just weeks before, about how school and music practice were going, and about whether he was being a big enough help to his mother.

“Here we are again,” Ernest wrote.

“I trust you are well and doing your best …

“There is not much doing here and it gets monotonous, still it will all be over one of these days and we will forget all about it.”

Alan had written back and was awaiting a reply when the telegram arrived saying that his father was missing presumed dead.

Alan treasured his father's letters for the rest of his life. Images: Courtesy the Harrison family

“It was something that really shocked the family,” Andy said. “But it wasn’t really talked about, growing up …

“I think all of them were somewhat traumatised by it, especially Ernest’s daughter, my Auntie Patricia.

“We went to the dedication of the Canberra memorial on Garden Island 30 years ago and after the service I rang to let her know that we had been and how moving it was and she just fell apart.

“She said she’d never been able to accept it, and she was just in tears...

“I guess that generation kept a lot of things close to their chests. There were so many ships lost, and so many people who died, even just on Canberra.”

Today, Ernest Harrison’s name is listed on the Plymouth Naval Memorial in the United Kingdom, and on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, among the names of almost 40,000 Australians who died while serving in the Second World War.

Ernest in an undated photograph. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

Alan and his father had been writing to each other during the war. Alan's final letter was returned unopened. Image: Courtesy the Harrison family

His story was told in a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial, attended by several generations of his family.

“It brings it a lot closer to home,” Andy said.

“To me, it’s about respect …

“There’s actually a quote from the prime minister at the time where Curtin said, ‘By their devotion to duty, the men of HMAS Canberra have made the greatest and noblest sacrifice for their country.

“And that sort of sums it up from my perspective. Those men were out there, serving their country.

“And they can’t give much more than their lives.

“I’m very sad I never got to meet him.

“And it’s just so sad to think back, but I’m pretty proud of him.”

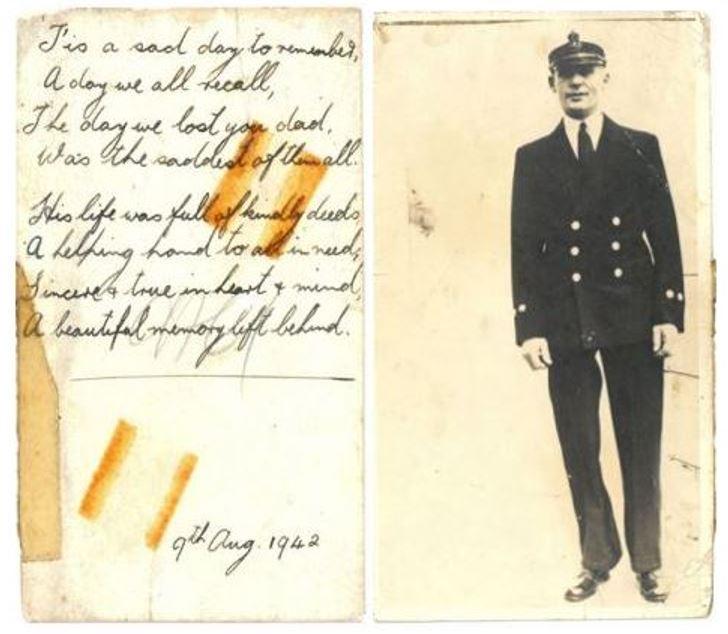

Alan Harrison wrote a poem about his father on the back of his photograph. Photo: Courtesy the Harrison family

Today, when Andy looks at the image of Canberra on his wall, he thinks of his grandfather and the many lives lost.

He treasures his grandfather’s war medals and photographs as well a tiny notebook that he kept from torpedo school.

When he turned over one of the photographs, he discovered a poem, written by his father, Ernest’s son Alan, as a boy:

“Tis a sad day to remember, a day we all recall;

“The day we lost you dad, was the saddest of them all.”