'It just seems to matter'

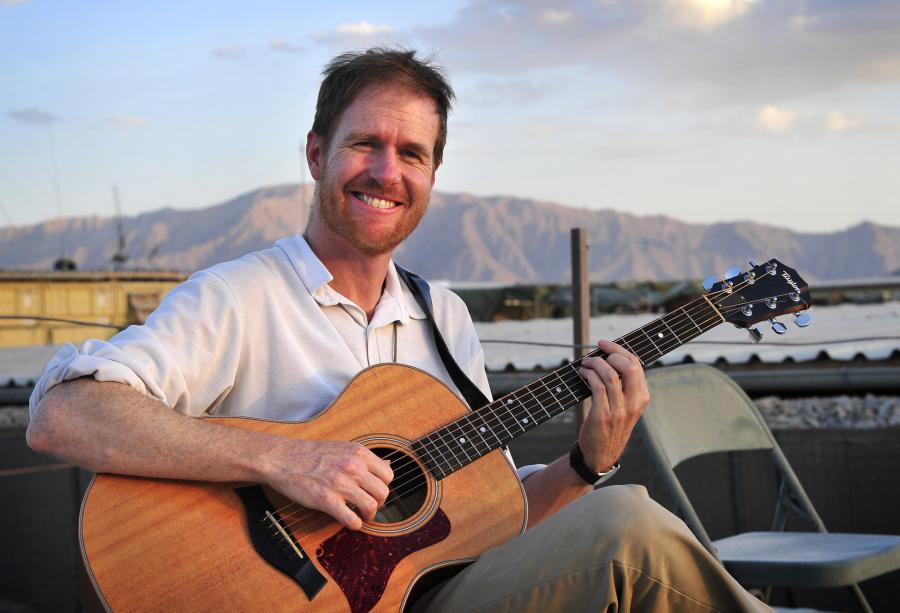

Fred Smith is a diplomat with a difference. Described as “Australia’s secret weapon” in international diplomacy, he was the first Australian diplomat sent to work in Afghanistan’s Uruzgan province in 2009, and the last to leave.

But it’s his second career as a folk singer and musician that captured the hearts of many when he wrote a song about the death of Australian soldier Ben Ranaudo, who was killed in July 2009.

“Dust in Uruzgan” struck a chord with Australian troops serving in Afghanistan, and a second song, “Sapper's lullaby”, became an anthem for soldiers and their families.

“I think most guys who serve in these environments would like to think that if something happened, they would be remembered,” he said.

“We never went anywhere without the protection of sappers: combat engineers travelling at the front of the patrol – a dog, metal detector, and 60 kilograms of body armour – crawling along at about a metre a minute, carefully scouring the ground.

“It’s very dangerous and difficult work, and we lost seven sappers in our time in Afghanistan, including two on the morning of 7 June 2010: Darren Smith and Jacob Moreland…

“That was the first double casualty we’d experienced there in Uruzgan, and it was at the beginning of a very difficult summer for us.

“I felt the grief around the base, and two days later I went to their ramp service ... It was just devastating to see these caskets and these young faces in the photographs …

“I went back to my office that afternoon to write a cable to the Foreign Affairs department, and ended up writing ‘Sapper’s lullaby’ instead.”

Fred will perform the song at the Australian War Memorial’s 2019 Anzac Day National Ceremony in Canberra, in a moving tribute to those who have served.

“I’m sure writing these songs helped me process what I was seeing and hearing, but also what people were feeling on the base,” Fred said.

“You are just going about your work on an ordinary summer’s day – and it’s actually quite fun working there; it’s fascinating and it’s busy, and you’ve got your mates, and life’s interesting – and then suddenly [he clicked his fingers] like that, everything changes.

“This one, it came out of nowhere; we hadn’t lost a soldier [in] … about eight or nine months … and then two soldiers were killed, and in the ten weeks that followed we lost another eight.”

Fred’s role in Afghanistan was to build relationships with tribal leaders to improve cooperation and understanding between the local community and the coalition forces, but he found himself in a unique position to understand both sides and share their stories.

“In 2009 the government decided to send diplomats in to work alongside our troops in Uruzgan province and I put my hand up,” he said. “The first morning I was there, there was a ramp service for Ben Ranaudo … so I was struck at once by … the gravity of it, [and] the contrasts…

“You land on this old Russian-built dirt airstrip in the middle of the Afghan summer and you get out, and it’s dusty, and it’s hot … but it’s a very tight community. You all eat in the same dining room, and you go to these ramp ceremonies, and you’re packed in there, and you just feel and see the grief that others are feeling, and … to see young men weeping over a casket, you’ve got to do something with all that …”

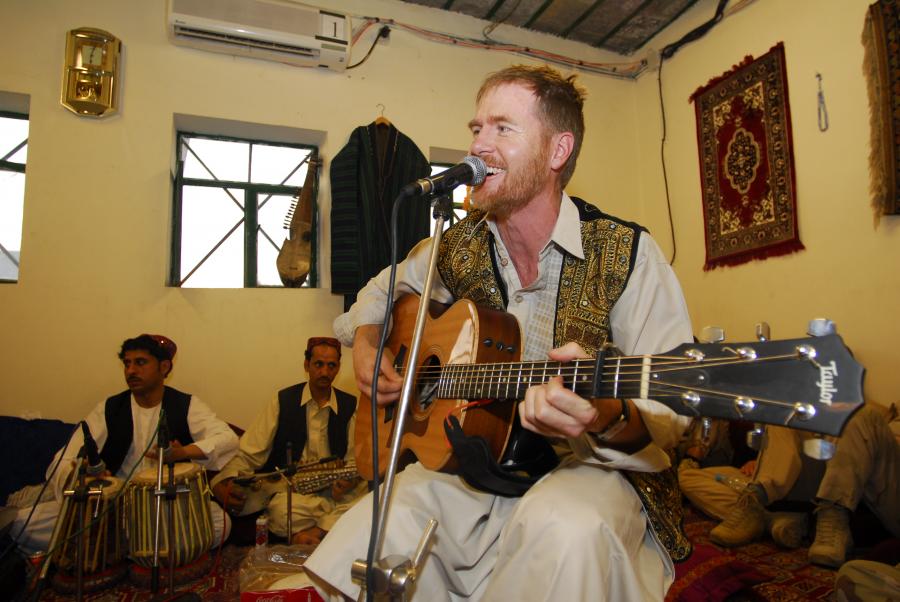

For the first three months, Fred stashed his guitar under his bed, but eventually he started writing songs and putting bands together. Accompanied by a nurse who sang, a quartermaster who played the guitar and an Afghan cleaner who played the djembe, he played regular concerts at the multinational base in Tarin Kot, where his songs became a hit with the soldiers.

He even learnt to play the Last Post on harmonica one night to help a contingent from 6RAR mark the anniversary of the battle of Long Tan at a makeshift ceremony at Forward Operating Base (FOB) Mirwais in the Chora Valley.

“I kind of grew up in a hyper-rational environment of diplomats and aid workers, and then went to boarding school where excessive emotional expression was not encouraged, and through all that music was a very private source of joy and consolation, and I think that’s why it’s also important to the world of soldiers,” Fred said.

“They’re not encouraged to be that expressive of their emotions and music short-cuts that for most people, including soldiers …

“We had these wonderful nights where we played music; Afghans, Dutch, Australian soldiers all reeling around a room and dancing …

“It breaks barriers down … and there were just magic moments of connection like that…

“When I got home, I began to feel that I had a role in telling the story, and that’s pretty much what I’ve done since.”

Known for his gentle wit, Fred carved a role for himself in Uruzgan, writing a collection of powerful songs about his experiences and the realities of life for soldiers in Afghanistan.

“It’s a tough and stressful environment, and you just need something to ease the pressure,” he said. “People are working 11-hour days, six and a half days a week, and a lot of serious things are happening, but there’s also a bit of natural comedy when you’ve got 1,000 guys out in the desert, mucking around and trying to do difficult things. There’s a certain natural slapstick to it all…”

His comic ditty “Niet Swaffelen op de Dixi”, entreating Dutch soldiers not to do unspeakable things in the portaloos, became a hit with the Dutch military, and Fred toured Holland in November 2010 on the strength of it.

“There were moments at the beginning of my time in Afghanistan when soldiers were like, ‘What’s this bloke doing here?’” he said. “But a year later, everyone understood it was a whole of government mission, and there were 10 of us DFAT civilians there.”

It’s a career that Fred seemed almost destined for.

Iain Campbell Smith (Fred is a boarding school nickname that stuck) was born in Canberra in February 1970 into a world of diplomats.

His father, Richard “Ric” Smith, was a senior public servant and diplomat who served in five overseas posts including as Australian ambassador to China and Indonesia, before becoming the secretary of the Department of Defence, and then Australia’s Special Envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan.

For Fred, it was a fascinating start to life. He grew up “all over the shop”, and was just six weeks old when his family moved to India.

“I was induced so my parents could get away in time for their first posting, and they’ve been rushing me ever since,” Fred said with a laugh.

“I grew up in the kitchen with the cook and the staff and spoke better Hindi than I spoke English. I’d speak Hindi with the [maid] and the cook and the bearer, and then my parents would try and practise their Hindi on me. I’d just look at them like they were joking – ‘You don’t speak Hindi, you speak English’ – so I think it gave me an early awareness of there being two different worlds.”

It was during his father’s posting to the Philippines that Fred first discovered the guitar, learning to play at the age of nine.

“I was watching cartoons on a Saturday morning and I saw Robin Hood fire an arrow out of a lute, and somehow … it all just intrigued me,” he said. “I remember at the time there was a Beatles cartoon and some combination of that caused me to ask my parents for a guitar. I don’t know if they regret it to this day, but that’s what happened … and the very Spanish guitar tradition the Filipinos inherited shapes the way I play.”

At 12, he went to boarding school in Canberra, where he earned the nickname “Fred”.

“I had a passion for tennis and wanted to become a professional tennis player,” he said, laughing once more. “But it didn’t work out, so I became a sort of folk-singing diplomat instead; it’s not a bad compromise, but I’d still like to be a professional tennis player.”

He went on to study law and economics at the Australian National University and joined the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1996.

“My father and my ‘uncles’ … used to sit around the dinner table talking about work, and it all seemed fascinating to me,” he said.

“I was an ambitious young man … but then I developed this sort of folk songwriting thing, which kind of threw a spanner in the works, and I was torn between a promising career as a diplomat and an unpromising career as a folk singer, and I ended up proceeding, through a very sophisticated process of indecision, to forge two careers.”

He started out performing comedy and drinking songs in bars around Canberra, but “stumbled on more serious stories” during peacekeeping operations in Bougainville and Solomon Islands.

“I always loved songs, and song-writing, and storytelling, but never wrote a song until I was 26,” he said. “It was always a conflict for me, ‘do I pursue this, or do I pursue that’, but happily when I went to places like Bougainville and the Solomon Islands I found I could do both. People love music there, and if you’ve got a guitar you don’t have to explain why you are in a village. It gave people … a reason to get together and it was part of creating a general feeling of optimism.

“Music is a short cut to people’s emotional worlds, and it takes a relationship from being transactional to personal … Barriers come down and … it humanised us peace monitors to the local people.”

He became something of a celebrity on Bougainville, hosting his own pidgin language radio show, and collaborating with the Australian Army and local musicians to record and release a cassette of his Pidgin language songs called Songs of peace.

“We’d come to Bougainville after eight years of really bitter localised village-to-village fighting and disruption and chaos, and we were part of a process of turning all that around, so it felt good,” he said.

“It’s a very psychological process, the peace process, and people need to feel confident that it’s going to endure. It needs a base level of optimism to work, otherwise people will go and dig their guns up again, so music and monitoring I found this happy confluence between what were previously conflicting passions for me.”

A “pathological storyteller”, Fred has always had the impulse to document things.

“I think it’s my response to the transience of life,” he said. “I became aware of death quite early in my life … In the Philippines I remember seeing a guy get killed on the street at the age of ten and just thinking, Jesus …

“In the face of that, I’ve always had the impulse to document, and I think that’s where I’ve been able to play a role, aside from the diplomatic work that I did… I think that’s why I wrote so much in Uruzgan. I was deeply immersed in that world … reading, writing, thinking, and talking to people about this complex environment … till it started to come out of my pores and in to my songs…

“As you’re going to sleep, things start running around in your head, and you start to write them down. I would record them onto a little phone … and then it just starts to come out. I found I didn’t have time to sit down and sort the songs out until I went on leave, and often the minute I got on the plane, I’d just start haemorrhaging lyrics, and write three [songs] in a week.”

He recorded his thoughts in 26 red hard-bound books, which became the basis for his songs and his book, The Dust of Uruzgan, about his experiences.

“I kept diaries, firstly for my own sanity,” he said. “You’re in this intense environment in a shipping container with seven soldiers and you just need some private headspace … and a way to debrief … I also had a sense that this reality that I was living in was worth documenting.

“I started out running both a personal diary and a work diary but it just didn’t work, and in the end it blurred. I’d have a meeting report and a draft cable, and then the beginnings of a song lyric, and then my own personal therapy stuff, and then another meeting report – all in handwriting that would be illegible to anyone else …

“I remember one night, I was asleep at one o’clock in the morning in the accommodation lines - these clusters of hardened steel shipping containers we called chalets. I got up for a pee and … and then suddenly, wham, a … rocket hit the roof. Everything just shook, and dust scattered from the ceiling, and everyone sort of piled out of the shipping container.”

He remembers he was joking with colleagues to relieve the tension, when another rocket landed 50 metres away.

“We felt the blast wave, smelt the cordite, and scurried back into [the shipping container], and just didn’t go back to sleep that night,” he said. “It’s stark moments like that when you realise that someone just tried to kill you, and there’s a palpable sense of the malice at the other end of the rocket.”

It was a persistent sense of vulnerability Fred and others faced every day while working on the main base in Tarin Kot, amplified when Fred moved up to a small forward operating base in the Chora Valley in July of 2010.

“When you’re on an FOB that small, it’s basically a gate and a wall between you and anyone with malicious intentions,” he said.

“I remember one time a rocket – an RPG – flew over my head and [there were] tracers flying a few metres over me. It was a fair way over my head, but you think, okay, someone’s having a go at us, and every time you walk out of the base, you know, you might walk past the saddle bag of a donkey and think, ‘ if there’s a bomb in there, I’m gone,’. That summer there was a real sense that the Taliban were stalking us.

“We weren’t in hardened steel shipping containers up at the FOB – it was a tent – so if a rocket flew overhead, it was just a matter of luck whether it landed on you or not.

“I’d never had that sort of palpable sense of having my life threatened, and I was lucky, I went in and out of the FOB everyday surrounded by these American soldiers whose job was to protect me, but anything could go wrong.

“A year later the guy who came to replace me, Dave Savage, was walking the same roads [with] the same protection team and a young suicide bomber crept into the package – 70 ball bearings in the back of his legs. He’s in a wheelchair now. When word of that came through about what had happened to Dave I just thought, ‘It’s just luck; it could have been me.’”

Fred returned to Uruzgan for a second stint in 2013 as the Australian mission in Uruzgan was drawing to a close. In the final days of the mission, he was asked to perform at a commemoration ceremony at Tarin Kot for the families of the Australian soldiers who had been killed in Afghanistan.

“I had just played ‘Sapper’s Lullaby’ [about Darren Smith and Jacob Moreland],” Fred said. “And [I] walked in behind the blast wall to get into the shade and pull myself together, and Darren Smith’s dad walked around the corner.”

It was an emotional moment for the pair, and one Fred will never forget. He’d already met Jacob Moreland’s father at a gig in Brisbane and was playing at a little folk club in east Melbourne when he first met Ben Ranaudo’s mother.

“I remember that night on the little plywood stage there. I said, ‘This is a song I wrote about a soldier named Ben Ranaudo,’ and voice from the back of the room said, ‘He’s my son.’

“I nearly fell off the stage, of course, and at intermission I went down and said hello … She was grateful that the song was there because it actually explained what had happened, whereas the inquiry reports were heavily redacted and written in quite official language.”

Today, he remains in touch with the families and hopes that by telling the stories he can help people understand Australia’s mission in Afghanistan, one song at a time.

“It’s important to the soldiers and to the families,” he said. “They want to know what happened, and they want to understand … and when you are doing that sort of work where you feel you are doing what you are meant to do, it is satisfying.

“I was amongst them, but not one of them; sure, I was sharing a shipping container with seven soldiers and working closely with them, but I’m not a soldier, I’m not one of them, but I was there, and I saw it all, and I think I’ve been able to play a constructive role in documenting it, which, in my experience, seems to matter to family members and to the soldiers themselves.

“Vietnam vets will tell you that they never felt understood in this country until John Schumann’s ‘I was only 19’ came out in 1981, so I think it’s important to tell the stories so that the new generation of veterans don’t walk the land as strangers in the way that a generation of Vietnam veterans did.

“It just seems to matter...”

Fred Smith will perform ‘Sapper’s Lullaby’ at the 2019 Anzac Day National Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial. His latest album, Warries, is out now.