Frederick Fletcher Fenn: 'One of the most terrifying experiences in my whole life'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised that the following article contains the names of deceased people.

Frederick Fletcher Fenn was serving as a driver with the 2/10th Australian Infantry Battalion at Tobruk when he risked his life to save two of his mates.

The two men – Corporal Sidney Amey and Private Murray Surridge – had been seriously wounded when a shell burst near them during a fierce artillery barrage.

Amey, with one leg blown off and the other fractured, was in danger of bleeding to death when Fenn ran almost 200 metres under fire to a utility, drove it back, and picked the wounded men up, driving into a barbed-wire entanglement.

“With the Jerries throwing everything at him, he cleared the truck and got us to safety,” Amey said. “I owe him my life.”

Fenn would later describe the incident as “one of the most terrifying experiences” of his life.

Today, he is one of 50 “Black Rats of Tobruk” to have been identified by researchers at the Australian War Memorial.

His story is one of many being shared by Michael Bell, the Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer.

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell has been working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served or are currently serving.

“Fenn’s story is really inspiring,” he said.

“And what’s really remarkable is that we’ve got it in his own words.

“In 1982, Fenn completed an Army Questionnaire for the History Department at La Trobe University in Victoria.

“He’s just really, really humble … and the dignity of the man shines right through all the way.

“You could have walked past him in the street and you wouldn’t have realised he was a hero, that he was a Rat of Tobruk, or that he was capable of such deeds.

“He goes to work every day and he doesn’t talk much about the war.

“He just wants to get married and to live out his life in peace and harmony, and he doesn’t realise how important he is, or how important his story is.

“Everyone should know about this man.”

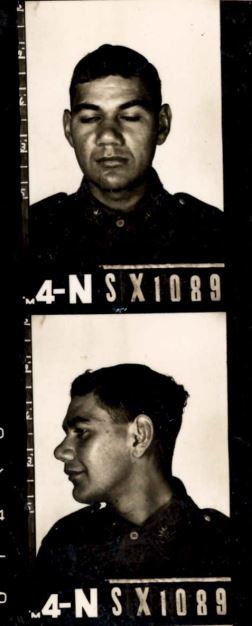

Fenn's enlistment photographs. Photo: Courtesy National Archives of Australia

Frederick Fletcher Fenn was born at Dalhousie Springs Cattle Station, north of Oodnadatta, South Australia, on 2 January 1916. His father Tom Fenn was the manager of the station and his mother was an Aboriginal woman.

“I was a part Aboriginal boy, who knew my father, and did see him from time to time,” he wrote in the questionnaire.

“But I never ever knew who my mother was … other than that she must have been employed on Dalhousie Springs Station.

“When I was five years old, I was brought south to Adelaide and placed in the Methodist Children’s Home Magill and was brought up there.

“Being in the House – each Sunday we would march to Magill Methodist Church, AM and PM to Sunday School … and church services.

“I was most grateful for completing the primary level [schooling, but I] didn’t have any choice to further this owning to [the] Depression years.

“My father was well known throughout the pastoral area … [and] although I did see him from time to time, [and] our association to each other was friendly etc – there wasn’t any real close ties.

“Perhaps there was reason to have me play low key to some extent, however, I must say, I have been most grateful for the things he did do for me in my early life.

“I’m sure my life would have been so very much different [otherwise].

“My attitude was one of gratefulness for being brought up in the Methodist Children’s Home Magill.”

Giarabub, Libya, March 1941: Personnel of D Company, 2/10th Australian Infantry Battalion, take a break during their journey to Giarabub from Mersa Matruh.

Tobruk, August 1941. Members of the 2/10th Battalion. Photo: George Silk 009516

Fenn left school at 13 and was working as a farm hand in South Australia when he enlisted on 20 November 1939.

“[I was] concerned with the German situation,” he wrote. “[And with] Hitler and the fanatical following he had.

“I had no design for big promotions – certainly not a Field Marshal’s Baton anywhere in my gear!

“[But] my schooling educated me to the point where the Empire was the one thing to belong to and be proud to be a member of.

“The Depression didn’t seem to have a very good future, [and] I was worried as to what mine was…

“My main interest was to try and better myself [but the] conditions didn’t allow any scope…

“I did try and join in and play football and cricket … [but] this was limited during wheat harvesting. This came before sport, and to keep your job you did bag sewing etc and liked it!

“The main problem I faced was to keep the job I had at all cost[s] until I could better my position, and I can tell you, this wasn’t easy.

“It was virtually a hand-to-mouth existence.”

He enlisted “mainly for adventure” and chose the army because he thought he would have a “greater chance of being accepted”.

He served in Britain, North Africa, and the Middle East, as well as at Milne Bay, Port Moresby, Buna, and Sanananda, before transferring to another unit, and serving in Solomon Islands and Bougainville.

A group of unidentified Australian soldiers inspecting two disabled Type 95 Ha-Go Japanese light tanks, which were found bogged down and abandoned after the fighting around Milne Bay, New Guinea.

Buna, January 1943: A wrecked Japanese 'Betty' bomber on the landing strip at Buna. Photo: George Silk

After the war, he was moved to find his experiences described in the history of the 2/10th Battalion, Purple and Blue.

The author, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Allchin MM, signed Fenn’s copy, saying: “Dear Fred. In appreciation of a great pal and grand digger.”

Fenn’s bravery in saving his mates’ lives during the siege of Tobruk had also been reported in newspapers around the country.

“A Tobruk dive-bombing attack was indeed terrifying,” Fenn later wrote. “[But] to watch at a safe distance could be spectacular.

“That incident on that night [at Tobruk] was one of the most terrifying experiences in my whole life.

“The other was at Buna, New Guinea, when we were advancing along the Buna airstrip at about 10 a.m. and we were cut down with machine-gun fire from the Japanese.

“I thought my heart would pound right out of my chest. We were close to their positions in Coconut Grove – we in kunai grass – and had to dig in.

“I tell you I prayed. I really prayed!”

Fenn suffered a serious gunshot wound to the right shoulder at Sanandana and was struck down by malaria on several occasions.

Sanananda, Papua. January 1943. An Australian manned tank in the attack on Sanananda moving through captured ground to make further advances.

He returned to Australia after the war and was discharged in late 1945. He joined the 10th Battalion Ex-servicemen’s Association as well as the Thirtyniners’ Association, and became a life member of the Rats of Tobruk Association “to keep contact with old buddies”.

“I had an admiration for anyone in any Australian service,” he wrote after the war.

“[The army] enriched my life to the full. I travelled. I met all types of people, and to have had the experience that I’ve had, I’m most grateful…

“[I] really did not have a home to go to … [but] I loved meeting people and [the] people I met in Wales [in the] UK, I corresponded with till they died a few years ago.

“When we arrived in Great Britain in June 1940, the thing that impressed me most was the civilian population, who carried their gas masks everywhere.

“[The British were] very brave, especially the fact [the] little kids going to school always had to [have] a gas mask kit along with their school pack…

“Their attitude to the conditions were very good, and talking to the people in general they were extremely calm about the whole situation. And appeared to be very glad to have us there …

“I did enjoy my stay in UK. History was something I enjoyed at school and to think – here I was visiting such places as the Tower of London, Billingsgate fish market, London Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly Circus, and Salisbury Cathedral, the lovely little English villages [and] inns in the country. [There was] no other way could I have been able to see all that.”

Salisbury Plain, England, 1940: Troops of 2/10th Battalion training in England.

After the war, he said he felt he’d “perhaps earnt a place in our society”, but that he found returning home “a bit hard”.

“Having had almost six years of army life and then suddenly a civilian … yes, that affected me a little,” he wrote.

“As one with Aboriginal blood, I found some aspects of our society rather strange.

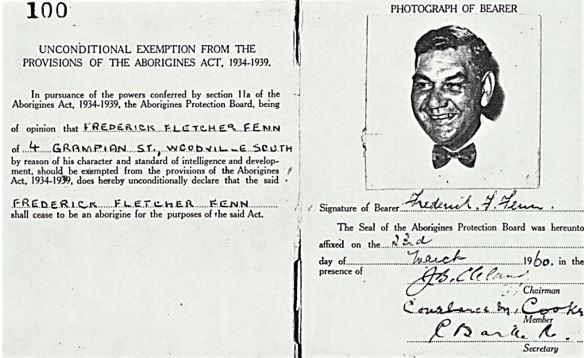

“Before, during and after the war it was law that I was unable to enter a hotel and drink alcohol – unless I had a special certificate to say I was a person in the opinion of three learned gentleman able to conduct myself in a proper manner etc etc.

“Even wearing an ex-service badge didn’t do anything towards helping my embarrassment when refused to be served, or asked to produce the certificate. This is ended now, thank goodness.

“[But] another example I found most surprising is the first job I had, or was to have, was to be the driver for the gang who looked after all the flood water drains west of Adelaide.

“When I was presented to the foreman and three workers as the likely driver and co-worker, the foreman first ask[ed] the chaps, ‘Would they be willing to work alongside me, or [me] alongside them.’

“Needless to say I was shocked, embarrassed, and will never forget it.

“Time has erased a lot of this resentment and now I’m retired – what the heck!

Fenn's Certificate of Exemption. These certificates were often referred to as a 'dog licence'.

“I have a bond among men which can only come about through [the] experience we had during the war.

“I meet with all types of ex-servicemen, and in no other way in my lifetime could I have been able to face, shake hands, and have the respect for them, or they the respect for me.

“A feeling of trust come[s] out when you live – eat – go on leave – lend money – gamble – and you sort out the grain from the chaff in an infantry battalion.

“I have chosen [discipline] as the single most outstanding quality [during the war] but surely honesty – trust – reliability – bearing all play their part?

“I can count brigadiers, generals, colonels, right down the line to fellow privates, as equals and I am so proud that [in] no way have I ever regretted joining the army.

“What a horrible waste of lives, time and material [war is].

“I consider myself most fortunate to be in the health I enjoy at present and hope to continue for some time yet.

Tobruk, Cyrenaica, August 1941. The tank chaser platoon of the 2/10th Battalion at Fort Pilastrino. Photo: George Silk

“When I looked like ending my army career and going into civvy life, I think I made a decision that, firstly, I didn’t want to finish in a ‘rut’ in the country … so a job in the city [it] was.

“[The] second thing [was] I’d like to marry. And [then] thirdly, I’d like to have a home of our own … [so] that when I was old [I] could live in peace … not being pushed or kicked around.

“Well, yes, I married a wonderful partner who shared my ideas … something we both settled into.

“Housing was extremely short [after the war] but after four years’ endeavour we were granted an opportunity to purchase an all-electric brick home where we live now. Our ambitions have all been realised … [and] we are most grateful for it…

“We are both enjoying our retirement in our little home … it’s ours [and] we are so proud of it.

“We still have many, many friends and pleasant memories of days gone by [and] we haven’t a regret in the world.

“At this time in our life, to have a haven whereby we can leisurely live in harmony with many neighbours and friends…

“I sure feel very grateful.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au