Gatenby's blanket: an embroidered service history

Given it’s the final month of another chilly winter here in Canberra, I felt it was fitting to share with you one of the cosiest objects on display at the Memorial: Corporal Clifford Gatenby’s embroidered blanket. Its unique design has captivated visitors with its richly embroidered images from across the globe, as well as the more familiar symbols of Australia. It is also a rare example of an object of its size to have been created in a prisoner of war camp and to have survived.

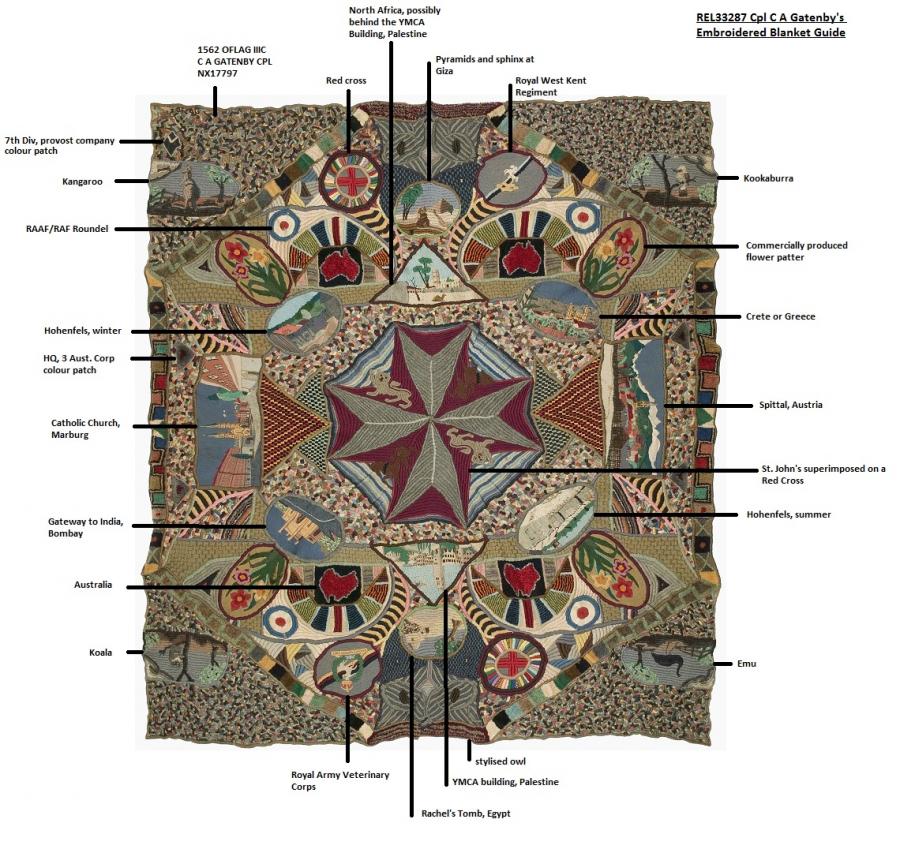

It started with a few stitches in the top left corner of the blanket where Clifford Alexander Gatenby claimed this blanket as his own and embroidered his prison number, his name and his service number. Between these early stitches and the last, Gatenby designed a visual history of his service and his experience as a prisoner of war. As it is a complex and intricate object, it may be best to journey through the blanket’s imagery following Gatenby’s service chronology.

When he enlisted at Martin Place in Sydney in May 1940, Gatenby was married to Kathryn Hilda Gatenby and they had two children. He had just turned 25 years old and he listed his occupation as ‘traveller’. The Gatenby’s lived at Point Pleasure in Bateman’s Bay. To represent home, Gatenby embroidered four panels in each corner of the blanket with a kangaroo, a kookaburra, a koala and an emu. He also included four vibrant red silhouettes of the map of Australia.

Gatenby was placed in the 7th Division’s Provost Company, the Military Police unit and Gatenby was quickly promoted to Corporal a few months later. The colour patch of his unit is embroidered in the top left corner of the blanket next to Gatenby’s name.

After initial training, Gatenby and the 7th Division left Sydney and landed in Kantara, Egypt in November 1940. It appears they stopped at Bombay, now Mumbai, as Gatenby has embroidered the Gateway to India in the bottom left of the blanket. Egypt was possibly the highlight of his journey as Gatenby represented several landscapes from North Africa in his embroidery. In the top centre of the blanket is a scene of the pyramids and sphinx at Giza with imagery from North Africa in the triangle beneath. It is possibly a view of the YMCA building in Palestine from behind. The front of the YMCA building is mirrored on the other side of the blanket with the adjacent oval stitched with Rachel’s Tomb in Egypt.

On the right hand side of the blanket beneath the flower pattern is a landscape from either Crete or Greece with what appears to be an orthodox church. Gatenby was sent to Greece before evacuating to Crete where he fought in the ill-fated Crete Campaign of May 1941. Although the existing garrison on Crete had been hastily strengthened with troops evacuated from Greece, they lacked transport, artillery and other weapons. During this battle, over 1700 Allied troops were killed and over 2000 injured. More than 11000 troops were taken prisoner, amongst them was Gatenby. According to his family, during what Gatenby described as the ‘glorious retreat without arms’, Gatenby had been supervising his troops’ evacuation and working continuously for over 48 hours when he decided to sit behind a rock to rest. He fell asleep and awoke to find himself surrounded by Germans.

Gatenby was first taken to Stalag 18 D in Marburg, Austria. Stalags were prisoner of war camps for non-commissioned officers. He spent about a year there before being transferred to Stalag 18 B in Spittal, Austria. After a couple of months he was transferred to Stalag 383 in Hohenfels Germany in September 1942. It was initially named Oflag III C, which you can see embroidered in the top left corner of the blanket, beside his prisoner number. Gatenby was at Hohenfels for the remainder of the war, which was almost 3 years in duration.

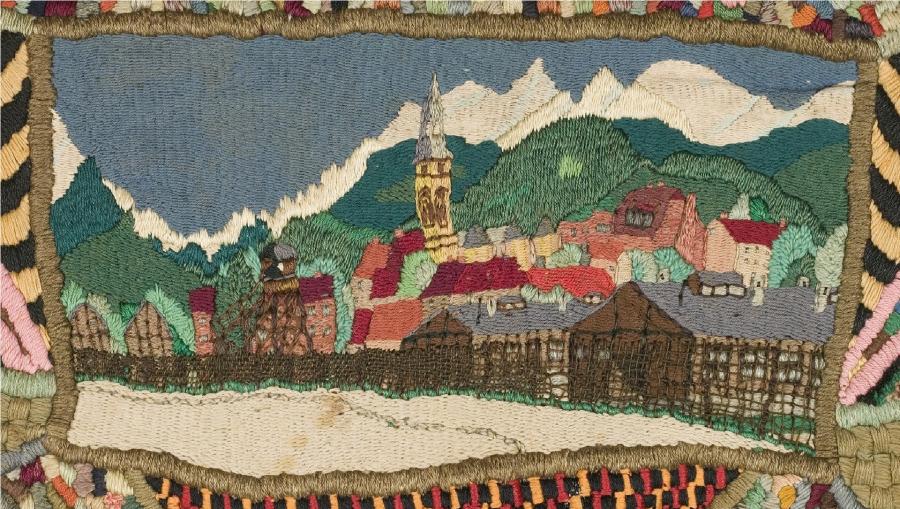

All these camps are represented in Gatenby’s blanket. On the right hand side is a view of the Catholic Church at Marburg amongst the town’s buildings. On the opposite side is a scene of Spittal from the prison camp where Gatenby has carefully incorporated the prison’s wall in the foreground and the snow-capped Alps in the background. There are two ovals with designs of Hohenfels. On the right hand side beneath a flower pattern is the Hohenfels prison camp in winter. Opposite this oval is another depicting the Hohenfels prison camp in summer.

Although it is unknown exactly when Gatenby started embroidering the blanket, it appears most of the embroidery was completed at Stalag 383 at Hohenfels, if not all. The clue is Gatenby's prison number, 1562. This number was given to him once he arrived at Hohenfels. Also, in his reports, he describes the conditions of the previous two camps at Marburg and Spittal as being much worse than at Hohenfels. Prisoners’ reports reveal Hohenfels had better conditions for enabling prisoners to pursue hobbies, such as embroidery.

Hohenfels has been described by one prisoner as being ‘a holiday camp’ in comparison to other camps. Conditions in other POW camps in Europe were quite severe particularly after D-Day in 1944, however the reports on Stalag 383 at Hohenfels suggest that this was one of the better camps. They had regular Red Cross and comforts deliveries, food was adequate, they were permitted to keep rabbits and egg-laying chickens and they were housed in huts with about 14 men per hut as opposed to the enormous barrack-like structures of many of the other camps. Unlike other camps, overcrowding wasn’t an issue. There were markets, theatre productions and even an art exhibition which included a number of embroidered pieces. Perhaps this blanket was exhibited. The commandant was described as fair, impartial and with a good sense of humour. Reportedly, if a prisoner escaped, they were punished according to how far afield they were before they were caught. The closer they were caught to the camp, the more severe the punishment.

Men strolling and sitting in the sun outside their barrack huts in 'Anzac Avenue' at Stalag 383.

It’s surprising that Hohenfels was one of the better prisons given that it was designated for non-working Non-Commissioned Officers. There were a number of British and Commonwealth officers who were particularly determined against forced labour which created difficulties for their German captors. As a result, Stalag 383 was created to send the recalcitrant Allied officers there in hopes to curb their influence over other, more willing prisoners. Given that Gatenby was amongst the first of the Allied prisoners to arrive at Hohenfels when it opened in September 1942, we can gain a sense of what kind of prisoner he probably was.

Gatenby initially used the darning needle from his Army issue sewing kit, but later had to create needles and crochet hooks for the Turkey work stitch from eyeglass frames, ground down toothbrushes and whatever other bits and pieces he could find.

He used wool from worn out items such as socks, scarves, and jumpers. Gatenby traded cigarettes from his Red Cross parcels to obtain different brightly colours wools from fellow prisoners, especially the British, whose families were sometimes able to send them clothing through Red Cross channels. He also corresponded with an aunt in England who sent him knitted items containing coloured wool especially for his embroidery. She may also have sent him the commercially produced pattern for the flowers that appear in four ovals on the blanket.

The RAAF or RAF roundels may represent Gatenby's younger brother, Flight Lieutenant Gordon Gatenby, an RAAF fighter pilot serving with 456 Squadron RAF. The two insignia are from different units. The rearing horse in the top right is probably the badge of the Royal West Kent Regiment while the badge in the bottom left is the Royal Army Veterinary Corps badge. Given the significance of many of the other elements in the blanket’s design, it’s likely these insignia belonged to other POWs who were close to Gatenby.

The centre of the quilt shows the St John’s cross superimposed on a red cross. St John’s ambulance often worked alongside the Red Cross to provide comfort parcels. The prominence of the crosses and the inclusion of two smaller red crosses on the blanket signify the role St John’s and the Red Cross had on prisoners’ lives. There are also two stylised owls embroidered into the pattern.

When Gatenby was released in early 1945, he took the blanket with him. He had so much work put into it, he didn’t want to leave it behind. He later said that he had started the blanket merely for ‘something to do’. Although he had not done much sewing before the war, his technique developed to the point where he could recreate scenes from his service in quite a sophisticated manner.