'It seemed unthinkable that anyone could get out of it as I did'

Portrait of George Furner Langley by Stella Bowen.

It was a moment that George Langley would never forget. At six minutes to 10 on 2 September 1915, he was hurled into the air and left fighting for his life when the troopship, HMT Southland, was hit by a German torpedo.

The Southland had left Alexandria three days earlier and was carrying troops to Gallipoli when it was attacked by a German U-boat in the Aegean Sea near Lemnos.

Langley was thrown into the air by the force of the explosion and fell through a hatch into the bilge as it filled with rushing water.

His story of survival is told at the Australian War Memorial as part of Against all odds, a special temporary exhibition featuring personal stories of escape and endurance from the First World War to Afghanistan.

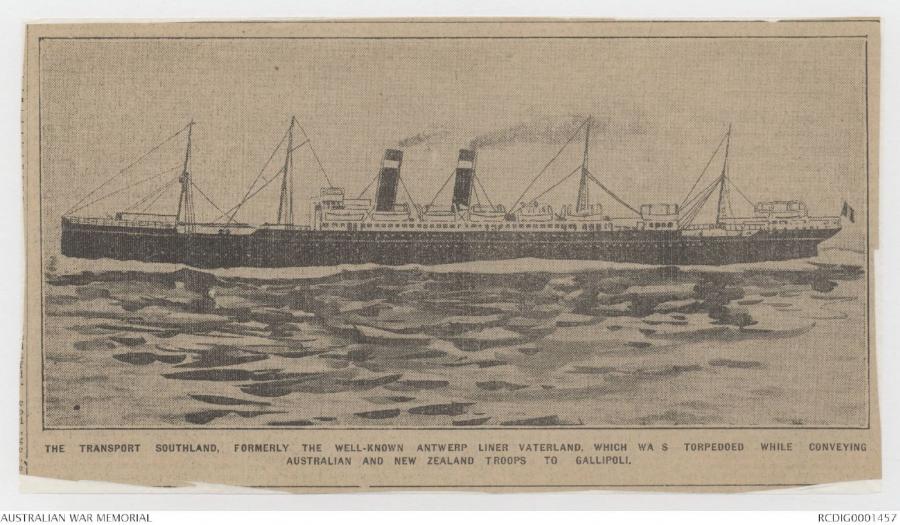

The troopship Southland after it was torpedoed. The photograph was taken from the hospital ship Neuralia.

Curator Dianne Rutherford said Langley’s story was a remarkable one.

“This exhibition is about ordinary people doing extraordinary things,” Rutherford said. “Some stories are over in a few minutes, while others drag on for weeks, but they are all amazing stories of how courage, determination, and sometimes a little bit of luck can be all that stands between a person and death, wounding, or capture…

“The waters between Gallipoli and Egypt were quite dangerous when George Langley was one of the officers travelling to Gallipoli on board the Southland. There were a number of German U-boats in the area and a number of ships had been sunk or attacked.

“He was incredibly lucky; he would’ve been killed if not for the water rushing into the bilge and breaking his fall.”

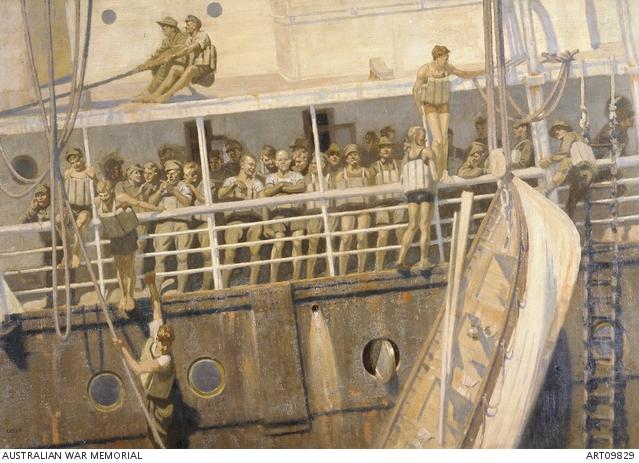

Fred Leist's Sinking of the Southland.

Langley later recalled the incident in a letter to his family from Gallipoli, and in a recording that was made in the 1960s and is now part of the National Collection.

“We were on our way to the front, pursuing a zigzag course to keep away from submarines,” he said.

“I’d just been made a captain that morning … and all at once there was a yell, ‘torpedo’ … They could see this white streak coming, and … I jumped up on this hatchway cover …

“It struck directly under that portion of the deck where we were standing and the next thing I remember [there] was a crash and rattle about my ears and I was in the middle of a mass of wreckage falling into the hold.

“The torpedo happened to hit, clean underneath us… The hatchway cover couldn’t stand anything like an explosion of that kind, so up in the air we went, and then down into the hold we fell.

“There was a hole right through the ship … [and] the rush of water into the hold saved me…

“[But then] I was under the water trying to get my head above the wreckage and I felt certain that I should not come out of the experience alive.

“I thought there was no chance of me getting up, and I imagined for a moment or two that this was the end, but I didn’t stop struggling…

“I eventually got my head above the water and there was no more thought about drowning as far as I was concerned… I struggled with my hands and my head bobbed up … and I took in all the air that I could take in.”

He was nearly overcome by sulphurous fumes from the explosion, but managed to catch hold of the combings of the hatch as he was pushed to the side by the rushing water.

“Even then I thought we were without a chance as I thought the ship would go down in a minute or two and we would not have time to get out of the hold,” he said.

“I hung on there until somebody came along and grabbed me by my tunic and my trousers and dragged me out onto one of the lower decks.

“I didn’t have enough left in me to drag myself out but a private from the 23rd Battalion grabbed me by the breeches and pulled me onto the decking…

“I pulled off my coat and managed to scramble up the ladders to the deck where the men were standing.

“When I reached there I found perfect order… My men were all standing there as they had been told to do and they were just waiting for somebody to … give them further orders.”

Battered and bleeding, Langley took control of his men and helped with the evacuation of the ship.

“I looked somewhat of a wreck and was unrecognisable,” he said. “[But] all the time our men were cracking jokes and singing songs.

“[The poet CJ] Dennis was quite right talking about ‘The Singing Soldiers’ on the Southland [in his poem]. It really did happen… There was a piano in the smoking room and the officers’ mess and some bright young fellow thought of the idea of getting the piano out…

“They dragged it out onto the deck and … played all the tunes that they’d been singing in camp and so on… It was a touch of genius … [and] they were extraordinarily cheerful...

“The behaviour was magnificent [and] no other word will nearly express it.”

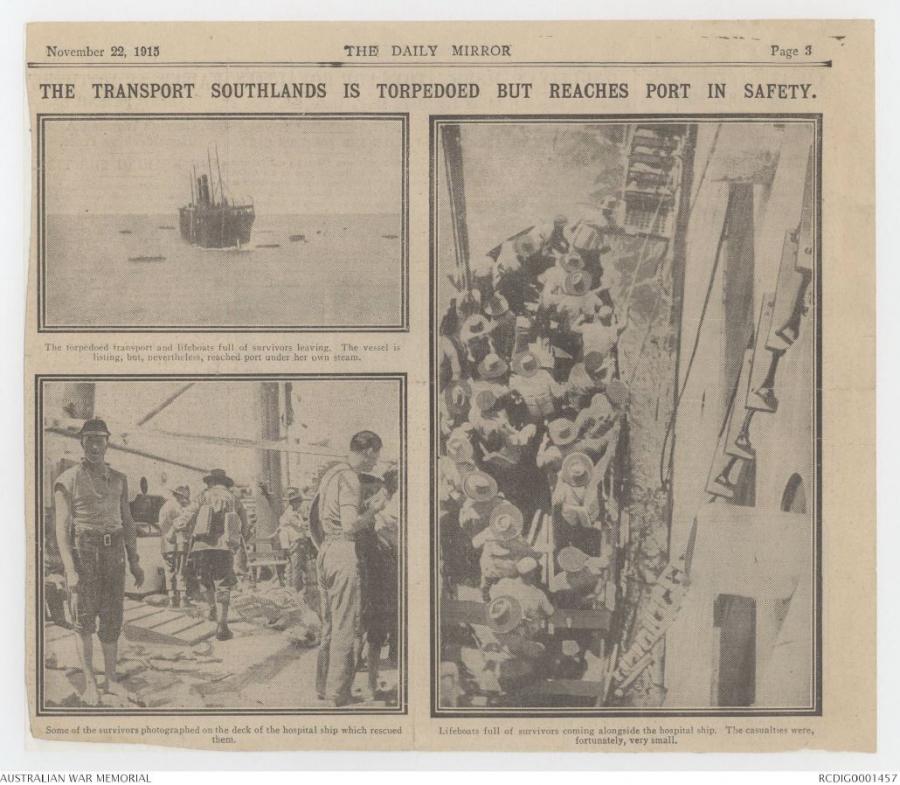

A lifeboat from the Ben-My-Chree passing a line to a lifeboat full of Australian troops from the troopship HMT Southland.

Despite his injuries, Langley insisted on proceeding to Gallipoli. He was the only one of those who had been blown up in the incident to go to the front. Many had been hospitalised and more than 30 had been killed, but Langley, despite medical advice, disembarked with his unit on Gallipoli on 8 September, and served there until the evacuation in December.

“I was knocked about a bit … and, really, by the time I got to Gallipoli itself, which was only a couple of days after that, I looked like a wounded hero already, but I was terribly keen that I should go on,” he said.

“I refused to go to hospital… I might have looked a bit of a wreck but there was not too much of a wreck about me... I really only had … bits knocked off me … there was nothing broken.

“Our trip from Lemnos to the trenches I shall never forget. I thought that I had nerves of steel till then and I found that they were jelly. Every noise reminded me of that experience and I almost expected to see another [torpedo] coming.”

George Langley, second from left in the front row, with members of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade in 1918.

Langley went on to serve in the Middle East with the Imperial Camel Corps and the 14th Light Horse Regiment, later taking charge of the 5th Light Horse Brigade and serving in Australia during the Second World War.

He kept the watch that he was wearing during the Southland incident for the rest of his life. He had bought the watch the day before the Southland left Egypt, and it had stopped at six minutes to 10 on 2 September 1915 – the moment he hit the water.

His daughter donated the watch to the Memorial after he died in 1971, and it is now on display at the Memorial as part of the Against all odds exhibition. For Langley and his family, the watch was a poignant reminder of his lucky escape.

“The experience was a novel, exciting and frightful one,” he wrote to them from Gallipoli.

“The streak of white making for our boat will live long in my memory… I am afraid that I shall be jumpy every time I get on board a boat while this war is on… It seemed unthinkable that anyone could get out of it as I did…

“They tell me that I should be thankful that I am here at all.”

Against all odds is on display in the mezzanine level of Anzac Hall until June 2020.