'It is a little-known story that deserves to be widely known'

Warning: this article contains images of deceased persons. It also features an image of a newspaper article containing racist terms and descriptions, the use of which reflects language and attitudes of the time.

George Matthews

When two platoons came under fire from hostile machine-guns at Chuignes on 23 August 1918, George Matthews sprang into action.

The 24-year-old lance corporal worked along a trench under heavy fire and bombed two machine-guns, capturing one and inflicting casualties on the crew of another.

The following day, he was badly wounded in his chest, neck and left knee, and reportedly lost the power of speech.

For his actions, Matthews was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

Today, his name is listed on the Australian War Memorial’s Indigenous Service list, one of the thousands of Indigenous Australians who volunteered during the First World War, despite not being legally allowed to do so.

The son of George and Mary Ann Matthews, he was born on the 17th of November 1893, in Quirindi, New South Wales.

The name Quirindi comes from the Gamilaraay language; Quirindi was part of the traditional lands of the Gamilaroi.

The first squatters settled in the area a few years before Quirindi Station was established in 1830. The station became a popular stopping point for passing teamsters and slowly evolved into the town site.

About 35 kilometres west of Quirindi, the town of Caroona was the site of Walhallow Aboriginal mission station, established about 1895. Young George was educated at Caroona.

His grandfather Thomas Mather, aka Matthews, was a convict from Derbyshire. Arrested for housebreaking, he was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was transported to Australia, arriving at Sydney Cove in 1832, and was assigned to John Eales, of Berry Park, who also owned the huge Walhallow Estate in its earliest days.

After gaining his Ticket of Freedom, he was given permission to continue working for John Eales at Walhallow Estate and Piallaway, and this is how the family came to be established at Walhallow. Thomas settled in the Quirindi area, and died in Gunnedah in 1886.

Matthews' paternal grandmother was Eliza Guess (later Gilham/Gillon), a Gomeroi woman who is listed as one of the apical ancestors on the Gomeroi Native Title Claim.

When the First World War broke out, George was determined to do his bit. He enlisted in Armidale, New South Wales, in February 1915 at the age of 21.

He left Sydney aboard the troopship Makarini on 1 April with reinforcements to the 3rd Battalion. The battalion took part in its first major action in Europe – the Battle of Pozières – in July 1916, and was involved in the fighting around Ypres in Belgium, before returning to the Somme to man the line during the horrific winter of 1916.

Matthews was wounded on Christmas Eve 1916, but returned to duty shortly afterwards. Throughout 1917, he and his battalion were involved in operations against the Hindenburg Line, spending a majority of the year in the line near Ypres.

In March and April 1918, the battalion was used to help stop the German Spring Offensive, before taking part in the final allied offensive near Amiens on 8 August 1918.

Matthews was repatriated to Australia in 1919 and married his wife, Catherine Sooby, at Quirindi the following year. He died on 17 June 1966, and was buried in Tamworth.

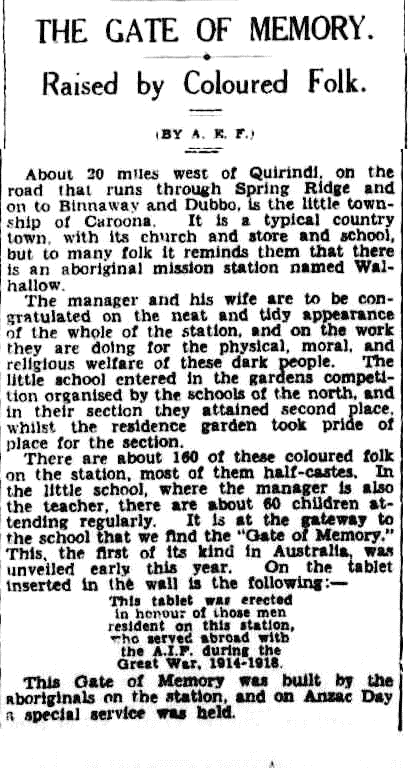

Today, a monument commemorates the Aboriginal residents of Walhallow Station who fought in the First World War. It is believed to have been the first monument dedicated to Aboriginal servicemen who served in the First World War. Originally unveiled as the Gate of Memory, the bronze tablet is now located on a boulder at the entrance to Walhalla Public School.

Australian War Memorial Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell said Matthews was one of thousands of Indigenous Australians who volunteered during the First World War.

“Despite lack of recognition of rights, denial of citizenship, and concerted efforts at exclusion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have served in conflicts involving Australian defence contingents since before Federation,” Bell said.

“When the First World War broke out in 1914, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had few rights, poor living conditions, and were not allowed to enlist in the war effort. Despite this, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people wanted to serve in defence of Australia, and were willing to change their names, birth locations, heritage and nationality in an effort to do so.

“Many who tried to enlist were rejected on the grounds of race; but many more enlisted successfully.

“They served on equal terms and were paid mostly the same rate as non-Indigenous soldiers with one notable exception, but when they returned home, they found that discrimination was still prevalent and had indeed worsened.”

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell is researching the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent, and is working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served or are currently serving.

“Today, the Australian Defence Force looks to recruits through the Defence Indigenous Development Program, and the actions and involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in all Australian conflicts since before Federation is far better known,” Bell said.

“We’re trying to encourage people to come forward and tell their stories … to help us tell the broader story of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experience.

“Because no-one saw them, perception of their service was skewed, and for a long time it appeared as if they had never existed.

“It is a little-known story that deserves to be widely known.

“If we can put an Indigenous face to the Anzac legend, we can use these stories as a stepping stone to reconciliation … using our past history to bring us together.”

Michael Bell is a Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man and is the Indigenous Liaison Officer with the Australian War Memorial. He is trying to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of any person of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who has served, or is currently serving, or has any military experience and/or contributed to the war effort. Michael would like to get further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au

The inclusion of George Samuel Matthews DCM on the Australian War Memorial’s Indigenous Service list would not have been possible without the generous assistance of descendants of convict Thomas Mathers. Their research and assistance is greatly appreciated, as is the ongoing assistance and collaboration of a talented, supportive and dedicated network.