'I'd always wanted to serve'

Glen Braithwaite as a 17-year-old. Photo: Courtesy Glen Braithwaite

Glen Braithwaite was sitting in a gun pit in East Timor when he heard what he thought was gunfire.

It was 31 December 1999, and people around the world were bracing themselves for chaos as midnight approached.

There were fears computer systems would collapse and stop working at the turn of the century as the calendar switched over to January 2000.

“We were there for the Millennium,” Braithwaite said.

"Half of my troops had the night off and some of us took a break from the command post and manned to guns to give the troops a break.

“So on the night that everyone was worrying about the Y2K bug, and whether it would stop all our computers, we were in a gun pit in Suai, close to the Indonesian border...

“We heard gunfire and we thought, ‘Oh no, something is happening.’

“But it was the just someone in the distance firing shots or setting off fireworks, likely to celebrate the New Year.

“But we didn’t know that at the time.”

Glen Braithwaite on the radio, on the extreme left of the landing craft, about to hit the beach at Suai, having launched from HMAS Tobruk. Photo: Courtesy Defence

Braithwaite getting a briefing from the New Zealanders who had secured the beach head. Photo: Courtesy Defence

A retired Australian Army engineer, Braithwaite had deployed to East Timor in 1999 as part of the International Force for East Timor (Interfet). The multinational peacekeeping taskforce had been mandated by the United Nations to address the humanitarian and security crisis which took place in East Timor from 1999–2000 until the arrival of UN peacekeepers. He returned to East Timor in 2006 as part of Operation Astute following unrest between elements of the Timor Leste Defence Force.

“I joined as a 17-year-old, and recently retired as a 50-year-old, so I have been an army officer most of my life,” Braithwaite said.

“I started as a reservist when I was still in Year 12, but as soon as I finished Year 12, I went to Duntroon and then became an officer in the Royal Australian Engineers.

“I was posted to the 3rd Brigade so we were the first ones into East Timor after the long peace.

“They said we were going to be deployed for 40 days, but it turned out to be six months…

“We were the first to go into Suai in the bottom part of East Timor, and we were some of the first people on the scene where the Suai Church massacre happened... The trauma of seeing the bloody stairwell of the church, and the charred remains where bodies had been burnt, those things stood out to me.

“Then when East Timor blew up again in about 2006, I went back in again...

“I’d always wanted to serve. Typical country boy. I saw Army as being a great career, but one that was meaningful to the nation as well. And before I knew it, I’d done over 30 years.”

Leading the Remembrance Day service in Suai on 11 November 1999. Photo: Courtesy Defence

Having retired from the army, Braithwaite is now focusing on his art.

“I did drawing as a child, but it wasn’t until I got out of the military, that I did some art classes, and those art classes just reinvigorated my love of drawing and putting some sort of mark on a canvas or on the page,” he said.

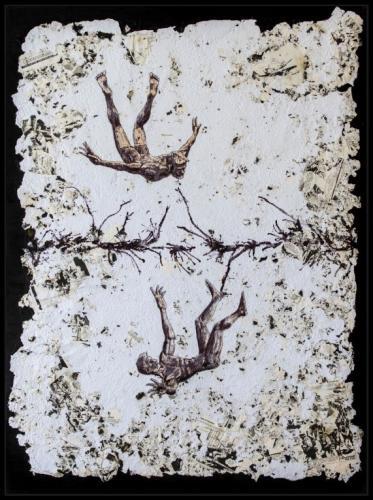

His artwork, Falling Flying Diving Drowning, was one of the highly commended artworks in the 2022 Napier Waller Art Prize and has been on display at Parliament House in Canberra.

"I realised I had some unconscious biases – now conscious biases – about mental health and trauma," he said.

“I often didn’t understand why some people were having PTSD and trauma and others weren’t, but I realised I was looking at it from my perspective, not from theirs.

“It wasn't until I thought: 'You know what? I need to look at it from their perspective.’

“Although the situation may appear identical, the human experience is not.

“Their perspective, their history; they’re all things that contribute to how they look at the world.

“To better understand mental trauma, I needed to strip ideas of uniforms, ranks, and identity and look at the person from every angle with an altered perspective.

“So I did the artwork Flying Falling Diving Drowning to reflect that if you look at things from a different perspective you can start to appreciate it from another side.”

Glen Braithwaite's work Flying Falling Diving Drowning was highly commended in the 2022 Napier Waller Art Prize.

The artwork is mounted on a 360-degree rotating bracket to enable the viewer to interact with the painting and alter their perspective.

“It goes against every fibre of your being to spin or touch a bit of artwork but I needed to do a piece that people could look at from a different perspective,” he said.

“The artwork intentionally spins so that a person who might appear to be flying one moment, may be falling or drowning the next.”

Braithwaite shredded and incorporated parts of a slouch hat into the work as well as comics that he read as a child.

"I suddenly realised that I needed to incorporate my history into the canvas,” he said.

“I am who I am because of my experiences and how I grew up, so ... I embedded my own experiences in this work by recycling my childhood Commando comics and shredding my first slouch hat to create a unique, personal and war-torn textured canvas.

“I cut it up into little pieces, and soaked it for ages to try and get it to loosen up, but it didn’t loosen up, so then I ran it through the blender.

“You will see little chunks of slouch hat – bits of the buckles, the straps – hidden throughout the artwork … which was a nice way of incorporating my own history... but I did break my wife’s blender making it.”

The figures were drawn in ink and highlighted with bleach.

“Painting with bleach is like gradually recognising your unconscious biases,” Braithwaite said.

“It’s a really slow process. You paint it, and then when you put the highlights on, you have to wait for the bleach to kick in.

“So it forces you to be patient.

“It’s so easy to overdo the bleach, and then all of a sudden you lose everything, so diluting the bleach and working out the right blends was all part of the trial-and-error process.

“I realised I had all these unconscious biases around PTSD and trauma, but if I can erase ink, then I can change my mind, and that was the idea of painting with the ink and the bleach …

“Nothing, not even opinions, should be impervious to change.”

Glen Braithwaite: "Nothing, not even opinions, should be impervious to change."

He hopes people will see his work Falling Flying Diving Drowning as an invitation to consider other perspectives and begin examining any unconscious biases they might have.

"By looking at something from a different perspective, it gives you a better understanding, a better appreciation, of what it is you're looking at, as well as some empathy,” he said.

“And that’s why I wanted to create a piece of art that was a little bit tactile…

“It's got to be touched ...

“And if you're prepared to look at things from a different angle, you can only be better off.”

A keen photographer as well, Braithwaite is excited by the artistic challenges and opportunities that now lie ahead.

“I’ve only just started my art journey,” he said.

“I’d never really played in other art mediums.

“But I've always been a photographer.

“I've always carried my camera with me while I was out bush.

“It was just something that I always had.

“I'd rather take a camera in the back of my backpack than extra set of socks.

“So I've always got a camera with me.”

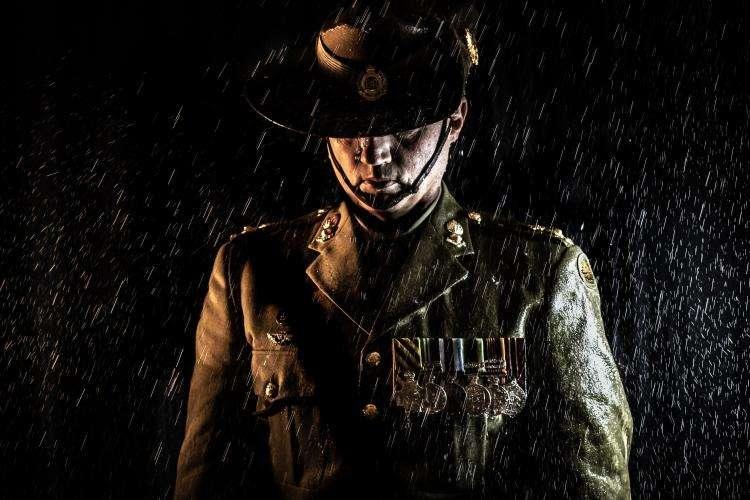

Glen Braithwaite's work Isolation was highly commended in the 2020 Napier Waller Art Prize.

His photographic work Isolation was highly commended in the 2020 art prize. His daughter assisted with the photoshoot, using the garden hose to create the rain.

“COVID-19 restrictions meant that for the first time in 32 years of service I was alone and isolated on Anzac Day,” he said.

“Never had I commemorated Anzac Day without my family, friends or colleagues by my side. My normal long, sombre walk up Anzac Parade to the Australian War Memorial Dawn Service was replaced with a ten-metre walk down my driveway. The street was empty.

“The image was created a week later ... to portray the isolation and stoic mood I felt on Anzac Day.

“It shows the superficial aspects of service life, the medals, the uniform, but more importantly it reflects the internal character, the resolve, the sacrifice and the strength of those who serve.”

Today, Braithwaite is grateful for his art, and for his time in the military.

“I’m very lucky,” he said.

“I always think, life is short, so don't stress the little things, get out and enjoy it.

“Try to make the most of every day, and live every day like it's your last.

“I loved my time in the military, and I still love it.

“My 32 years went by in the blink of an eye and I left the military on my own terms – healthy and happy.

“But retiring so early, I’ve still got a full career ahead of me, so art seems to be a great avenue.

“And now I can do things that spark joy.

“It’s been the beginning of a new journey for me.

“I’ve been introduced to a veteran arts community that I had no idea about.

“It’s just mind-blowing.

“And I can't believe it.

“It reaffirms in my mind that I might have made the right decision.”