Goetz’s gaffe

The National Collection is rich with material and stories relating to wartime propaganda. When thinking about this it is only natural to recall the graphic printed pamphlets and posters depicting strong emotionally charged messages eliciting support for the war and suspicion of the enemy. One vehicle for propaganda which is perhaps less well known is that of the medallion. During the First World War medallions were produced not only as commemorative and collectible items but also as a means of conveying messages and raising money for the war effort. This proselytising function is well illustrated by the notorious Lusitania medallion, created by the German medallist Karl Goetz in 1915. It demonstrates how a medallion – which was originally a private initiative – became a propaganda tool and an international scandal.

The medallist Karl Goetz was born on 28 June 1875 in Augsburg, Germany. He attended art school there before studying in the German cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Berlin from 1895-1897. He spent five years in Paris before moving to Munich in 1904. Goetz lived for his work and during his career, created 633 medallions. 175 of these were satirical. Today Goetz’s medallions grace the collections of many public institutions, as well those of private.

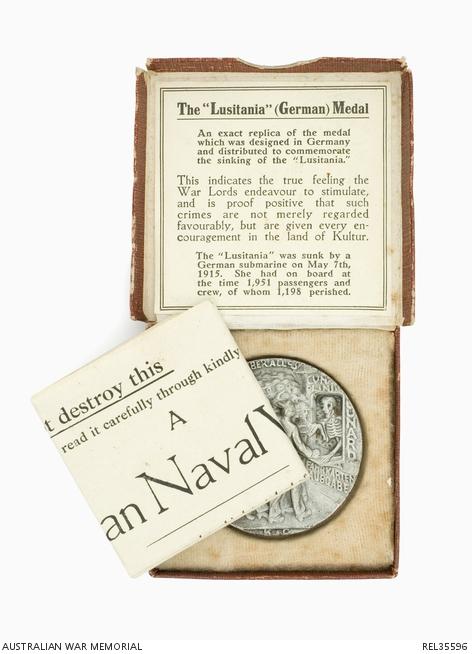

A British propaganda copy of the Lusitania medallion. The obverse can be viewed by via the link to the catalogue record.

Today, his best known medallion is the Lusitania medallion. The obverse of the medallion depicts, in high relief, the Lusitania sinking with war cargo spilling from her deck. Around the top edge are the words 'KEINE BANN WARE' (No contraband goods). In a panel at the bottom are the words: 'DER GROSS DAMPFER / LUSITANIA / DURCH EIN DEUTSCHES / TAUCHBOOT VERSENKT 5 MAI 1915' (The great steamer Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat 5 May 1915). The reverse depicts, in high relief, the skeletal figure of Death sitting at the booking office of the Cunard Line (marked with the legend 'FAHRKARTEN AUSGABE' or ticket office) who gives out tickets to a queue of passengers. These passengers refuse to heed the warning against submarine attack given by a caricature of the German Ambassador to the United States, Count Bernstorff. Around the top edge are the German words 'GESHAFT UBER ALLES' (Business above all). The extreme bottom features the designer's initials (KG).

The first issue of the Lusitania medallion was privately designed and struck by Goetz in August 1915 to mark the sinking, by German U-boat, of the Cunard liner RMS Lusitania on May 7th that year. She was nearing the end of her voyage from New York to Liverpool when she was sunk by a torpedo fired from a German U-boat near Ireland. Tragically, 1,198 (of the total 1,951) passengers and crew on board perished. The log of the U-boat stated that only one torpedo had been fired; however a second explosion led people to believe that two were fired. The speed with which the ship sank (taking only 18 minutes), and the second explosion, later led to rumours that high explosives had been secretly carried on board.

Germany claimed that the Lusitania was a legitimate target, because she was a listed British Armed Merchant Carrier (but had not been fully fitted out at the time), likely to be carrying war materiel, and was in the British war zone. However the British and American press were in uproar over the loss of lives. Goetz produced the medallion to castigate the British Government for what he saw as hypocrisy by a government who had used civilian passengers to shield the movement of munitions. Indeed, she was carrying live artillery shells and small-arms ammunition and had been carrying such ammunition for years, a fact that was withheld from the British public at the time. In addition, Goetz censured the government for having allowed the ship to sail despite Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare, the fact that the war zone included the waters around the British Isles, and their prerogative to destroy any vessels flying the flag of Great Britain in British waters. Her sinking was seen by allied powers as a crime that further exemplified the frightening measures Germany would take to secure victory. The event inspired outrage and an abundance of anti-German propaganda. It was also a turning point in the then neutral USA’s attitude to the war and US-German relations.

Goetz privately produced the medallion in a small run in August that year and it was sold in Munich and to some foreign countries. Now this is where the story gets interesting, as although the medallion was not officially sanctioned by the German Government, it was used as propaganda by the British Government. Goetz dated the event as 5 May – two days before the actual sinking. He later blamed this on an incorrect newspaper account. Unfortunately for him, the mistake was seized upon by the British propaganda machine. One of the medallions made its way to England, where it caused outrage. The British claimed it revealed that the sinking of the Lusitania was premeditated. Although the medallion was privately produced, the press claimed it was endorsed by the German Government, awarded to the crew of the attacking U-boat, and distributed throughout Germany.

The British issue of the Lusitania medallion, including the ‘explanatory’ leaflet. Detailed images of the medallion can be viewed by via the link to the catalogue record.

The British Foreign Office managed to obtain a copy of this medallion, photographed it and sent copies to the United States, where it was published in the New York Times on the anniversary of the sinking. The attention this attracted allowed Britain to capitalise on anti-German feeling by producing a boxed replica with an ‘explanatory’ leaflet intended to demonstrate Germany’s cruel actions against innocent women and children. The British copy can be identified by a number of factors:

- Instead of the German spelling, ‘Mai’, the date on the obverse reads ‘5 May 1915’

- The overall finish is much cruder and there is a loss of detail

- The text on the copy is slightly larger than the original

- They were made from white metal-plated iron rather than the bronze of the orginal

This replica medal, along with its accompanying leaflet, served to reinforce the stereotype of the brutal ‘Hun’ that British propaganda had been attempting to create. Copies were manufactured and sold to the general public from 1916 at a cost of a shilling each, the proceeds of the sales going to the St. Dunstans Blinded Soldiers and Sailor's Hostels and the Red Cross. It was eventually produced in the hundreds of thousands.[1] One even made its way to Australia, arriving in Newcastle on 23 March 1917 for display in one of the windows of Scott’s, Ltd, one of Newcastle’s largest stores.

This propaganda campaign was so successful that in January 1917 the Bavarian War Office ordered the manufacture and sale of the original medallion to be forbidden and all available pieces confiscated. Indeed these medallions remain scarce. Goetz corrected the date to 7 May in his second run of medallions; however the damage had been done.

The satirical medallion, 'Difficile est Satiram non Scribere'. The obverse can be viewed by via the link to the catalogue record.

Goetz defended the Lusitania medallion as satire and produced a subsequent medallion; It is difficult not to write a satire between 1916 and 1917, to support this. This medallion was a reaction to Lord Balfour’s Guildhall speech of 9 November 1916, during which he denounced the German Navy’s war against commerce. Balfour specifically referenced Goetz’s medallion and made a contrast between virtuous German utterances at the Hague conference in 1909 with piratical German behaviour on the high seas during the war.

Goetz attempted to undo some of the damage done with this medal by lampooning British attempts at propaganda. On the obverse, in high relief, is Lord Balfour (British First Lord of the Admiralty) showing the controversial object to a group of onlookers, which includes a caricature self-portrait of the artist and the British politicians Daniel Lloyd George and Sir Edward Grey. The irate figure in the background is either Winston Churchill or Prime Minister Asquith. Above them is the text 'DIFFICILE EST SATIRAM [sic] NON SCRIBERE' (It is not difficult to write a satire). Beneath is the text 'DIE LUSITANIA MVNZE GIBT LORD BALFOVR STOFF Z REDEN 9 XI 1916' (The Lusitania Medal gives Lord Balfour much to talk about 9 November 1916). The reverse depicts, in high relief, a Scotsman playing bagpipes and carrying a large poster referring to the Lusitania medallion, '...FLUG BLATT EIN DEVTSCHER SEE SIEG 1916' (…English bulletin. A German naval victory Lusitania Medal). Around the edge are the words: 'ENGLISCHE HETZ ARBEIT IN SCHWEDEN' (English agitation work in Sweden). It has been interpreted as an attempt to undo some of the damage caused by the Lusitania medallion by deriding subsequent British propaganda efforts, especially those aimed as Neutral Sweden and Norway.

Goetz was adamant that the medallion was only ever intended to castigate the irresponsibility of the Cunard Steamship Company and the British Government, which, despite warnings, placed passengers of the Lusitania in danger. It was never to be a triumph over the loss of human lives. In a letter to Rear Admiral (rt.) Lutzow, Berlin on 17 August 1932, Goetz wrote that he “…regretted it most sincerely that the hostile foreign countries used this piece in false interpretation for propaganda purposes…” Goetz’s gaffe, a most unfortunate tale of a misinterpreted artistic work, illustrates both an infamous event of the First World War and a different take on Allied propaganda efforts.

Further reading:

Cull, Nicholas John, Welch, David and Culbert, David, Propaganda and mass persuasion: a historical encyclopedia, 1500 to the present (Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, c2003).

Imperial War Museum, n.d., Difficile est Satiram non Scribere. Available from: < http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/11054>. [10 July 2014].

Imperial War Museum, n.d., The Lusitania Medallion. Available from: <http://archive.iwm.org.uk/upload/package/23/lusitan/index.htm>. [10 July 2014].

Kienast, Gunter W, The medals of Karl Goetz, (Cleveland: Artus Co., 1967).

Lusitania Online, n.d., A Deadly Cargo and the falsified Manifest. Available from: < http://www.lusitania.net/deadlycargo.htm> . [15 July 2014].

Nelson, Randy, n.d., “Sinking of the Lusitania and the Karl Goetz Medal”, The CN Journal. Available from: <http://www.rcna.ca/sample/lusitania.php>. [10 July 2014].

[1] In his answer to the Military Branch of the State Department in Berlin, Unter den Linden, dated 25 November 191 6, Goetz stated that 180 Lusitania medallions from the first issue were produced in total. Kienast, G. W, The medals of Karl Goetz, (Cleveland: Artus Co., 1967), p 14.