'I couldn’t tell you how bad it was'

Veteran Gordon Willoughby shares his story with Australian War Memorial Director Dr Brendan Nelson.

For almost 75 years, 95-year-old Gordon Willoughby has carefully guarded a collection of images from the Second World War in an old pay envelope in the drawer of his late wife’s dressing table.

He was with Australian forces in Borneo's south when it was liberated from Japanese occupation in 1945 and returned to Australia with a handful of black and white photos of the “indescribable” moment when the local Japanese commanders formally surrendered.

“The photos are very real to me,” he said. “We weren’t allowed to take photographs … but our senior officers said one of the ranks could take some just as long as he shared them with everyone else, and that’s how I came to have them over all these years … They are special to me for the story they tell, and I like to show people; it shows the reality of war and when the war finished.”

The Japanese surrendering. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

The photos were captured on a humble box Brownie camera and Gordon has kept them safe ever since. He recently travelled from his home in Sydney to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra to share them with Memorial Director, Dr Brendan Nelson, and talk about his experiences.

“I don't know if I could describe how I felt [when the Japanese surrendered],” Gordon said.

“We were all told to have our guns ready just in case it was some kind of trick, so … I had my two guns – one on the hip, and a .203 full of ammunition – but they walked down as calmly as that…

“We just led them up to this special tent we had set up with a table in it and that’s where they signed the surrender…

“I couldn’t tell you how good it was. It was absolutely wonderful. For the first time in the weeks that we had been there, that ground looked real good where I was standing.”

The Japanese being escorted by Australian troops. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

Gordon was 22 at the time. He had enlisted in 1942, when he was only 19.

“They wouldn’t take me in the army until I was 21 because my dad wouldn’t sign the papers,” he said. “I had three sisters and a mum and dad who were getting older, and I said to my dad, ‘Should I go?’ He said, ‘No, no, not yet.’ But I was called [up when I was 18], and that’s how I got into the army. I said to my dad, ‘You may as well be hung for goose as for a gander.’ So he signed my papers … and I joined the AIF.”

Gordon started in artillery and trained as a driver, but was later transferred to the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion, which had fought at Tobruk.

“They’d lost a lot of men over there, and that’s how I came to be in the Pioneers,” he said. “We used to march 24 miles a day … to toughen us up a bit … and at the end of 24 miles, I reckon I could have marched another 24 miles; I couldn’t have, of course, but that’s how I felt at the time.”

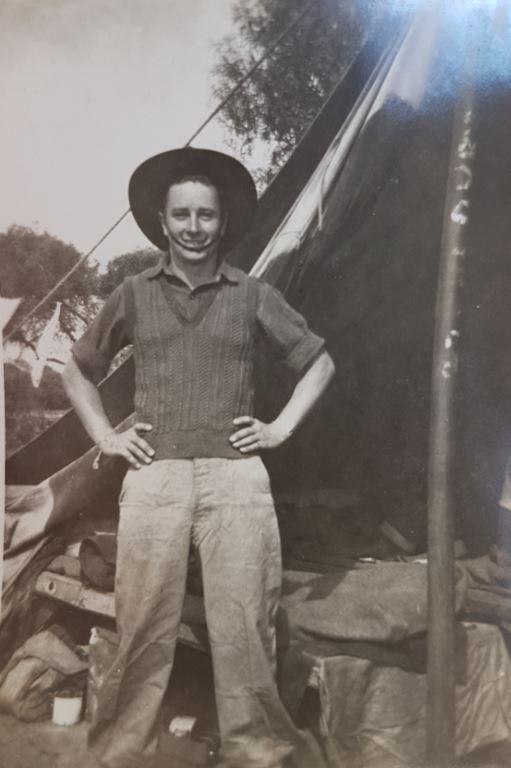

Gordon Willoughby enlisted when he was 19. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

He was sent to Milne Bay, Wewak, Morotai, and Borneo, and was with the 2/1st Pioneers when they came ashore at Balikpapan during the beach landings in July 1945.

“She was rough, alright,” he said. “And we were all sea sick. On the boat I was on, I counted 14 on mess parade, and even the sailors were feeding the fish over the side…

“On the front of those, were the LSTs – the landing ship transport – which took us in. They didn’t have anything in the front of them – no keel, no nothing – and they just used to wobble around like a duck and that’s why everyone was sea sick. We were up in the air, and down in the water, and it was wild country, alright.

“I had a camera in my kit, but the word came around that no one could take a camera in with us, except this one guy; he was allowed to go in and take photos, and the [photos I have] were the photos he took using the same [type of] camera as mine.

“I was glad I didn’t take mine in the end because when I jumped in the water, I was submerged, and it would have been the end of my camera…

Gordon Willoughby during the war. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

“I wasn’t a born soldier, so I had the wind up, I don’t mind telling you, for we clambered down the side of that LST in to a barge in the middle of the beach …

“I said, ‘I’m not going to jump off in front of the barge; if a wave hits the back of that and pushes it up, and I get caught in the sand, I’ll have both legs snapped off like carrots.’

“I jumped off the front, but off to the side, and there was no bottom where I went down, and I was completely submerged… I said, ‘I’ve got to get up out of here, there’s not much air down here,’ so I got up on my feet…

“I was twice as heavy when I got out of there because of all the gear I was carrying, and I ran up the beach and I got in the first big hole I saw – a bomb crater.

One of the amphibious trucks or "ducks" used at Balikpapan. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

“Long before daylight, the air force had bombed the tripe out of the beach where we were landing, and I said, ‘Oh, please don’t stop, please don’t stop.’

“They’d bombed it just like a match stick, and … we had a bit of a mud map … to decide where we were going to go… The chief said, ‘We’ve got to be on that sand hill by dark,’ and I said to myself, ‘Mate, if you’re there, I’ll be there,’ and we were…

“He said, ‘This is it, make yourself comfortable,’ so we started tearing into the ground, and I tell you what, I have never moved so much dirt in all of my life; I got a trench down very smartly...

“There was a tunnel in underneath … this little bit of a hill … and I said, ‘George, I’m not going in that tunnel and putting my head around there because I won’t be any use to Australia after that; we’ll go back and report all clear, but you and I, George, will watch that thing, and if there’s any movement there tonight, we’ll drill it.’ When we got back, no one came out, so we didn’t get caught or anything … and no one came out to kill us.”

Gordon treasures his collection of photographs from the war. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

A few days later they received the order to move forward.

“We marched … through this oil refinery that was absolutely burned out,” he said. “The big oil tanks in the refinery … were crumbled down – just like a Coca-Cola tin when you stand on them – and we were going through there with a bit of wind blowing on them. Sheets of iron [were] rattling, and we thought there were [Japanese] everywhere. There weren’t, but it was nerve-wracking going through there, and on the other side of the oil refinery we dug in again.

“From there, my job was to go shot gun rider, [just like in] the Western movies … up on the cabin … watching out in front, and … that was frightening. If there had been any [Japanese] there in that mangrove … along the river, they would have drilled us and made mincemeat of us in no time…

The Japanese arriving to surrender. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

“I couldn’t tell you how bad it was; it was terrifying, but that’s war … [and] that’s what war is like.

“In that jungle it was deadly; every bush was walking around in front of you, and if a bit of wind was blowing and the scrub moved, you drilled it …

“It was absolutely terrifying, but you’ve got your mates beside you, and you’ve got to go with them, shoulder to shoulder, that’s it …

“I don’t fear war now, and I can talk about it, but it was fearful at that time.”

He will never forget the joy he felt when the war was finally over.

“We heard that the Yanks had dropped a couple of bombs on Japan and very soon after that we got the word that they’d surrendered,” he said. “We didn’t know if the people in Borneo knew … so we just waited, and then we got a message from the beachhead that they had surrendered ... and that they were coming into our camp to sign up ...

“I think every gun in our little camp … fired up into the air. It was the end of the war … and I couldn’t tell you how wonderful it was.”

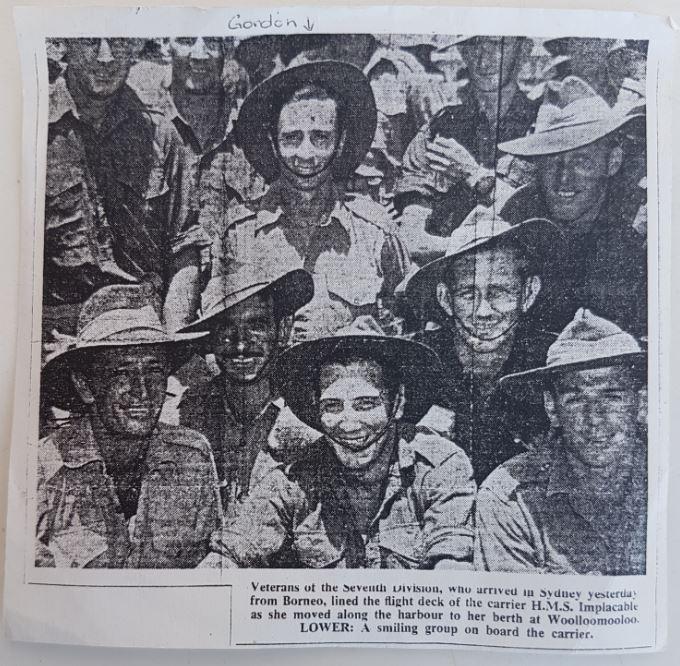

Coming home on the aircraft carrier HMS Implacable. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

He and his mates returned home on board the Royal Navy aircraft carrier, HMS Implacable; their delight clearly evident in an image published in the local newspaper.

“To me, the day HMS Implacable arrived at the Sydney Heads was the greatest sight of all,” he said.

“Not so long ago, the Australian navy sailed through Sydney Heads [for the Navy Review], and the bloke on the television said, ‘Have you ever seen a more wonderful sight than that?’ And I said to myself, ‘Mate, I can think of a better sight than that …’

“I’ve never seen Sydney Harbour look so nice. It was wonderful, and I couldn’t tell you how glad we were. It was absolutely marvellous.”

Gordon and his mates appeared in the newspaper the day after they arrived home. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

Of all the people Gordon was looking forward to seeing the most, none was more important than his future wife, Edna Lord. They had known each other since they were children and had grown up together in country NSW.

“She told me when she was five years old that she was going to marry me,” Gordon said.

“We were born in the same street in the Hunter Valley just five miles from Cessnock. It was a fairly long street in Abermain and her brother [Allan] was born the same time as I was born; wherever Gordon was, Allan was … and wherever Allan was, Gordon was.

“We had to hurry across a bridge there in Abermain, and according to our mothers we had to take Edna’s hand and go across while there were no cars coming, so we hurried across and we got off the bridge and up over a gutter onto a gravel footpath, and my mate Dick said, ‘I’m going to marry Edna when we grow up.’ She said, ‘No, I’m going to marry Gordon.’”

Gordon and Edna after the end of the war. Gordon is wearing the first suit he bought when he came home. Photo: Courtesy Gordon Willoughby

When the Second World War broke out, Edna also wanted to do her bit for the war effort. She joined the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force and was involved in signals intelligence work.

Gordon will never forget seeing her for the first time after the war: “She was dressed in her WAAAF uniform, and I can tell you, she looked fabulous.”

The couple married in 1949 and had two children; a daughter and a son. But Gordon was left devastated when Edna died from breast cancer in her 60s and their daughter lost her life to the same illness at age 50.

One of his prized possessions is a photo of Edna dressed splendidly in uniform. “She was beautiful … more so in my eyes … and from the day we married to the day she left, she loved me, and I loved her,” he said. “Mates asked me why I didn’t remarry and I always say, ‘I couldn’t because I’m still in love with my wife.’”

Today, he is grateful for his blessings and still considers himself fortunate; fortunate to have survived the war, fortunate to have married the love of his life, and fortunate to be able to share his memories and his photographs.

For Gordon, who turns 96 in June, it was important to visit the Memorial and pay his respects. He placed a poppy on the Roll of Honour in memory of all those who served.

“When I was having a look at the wall, I couldn’t talk,” he said quietly.

“I met a man who came here after the war. He was a German. He was servicing [General Erwin] Rommel’s tanks in the desert in North Africa, and … time and time again, Rudy said to me, ‘I don’t know why I was shooting at you, Gordon,’ and I’d say, ‘Rudy, I don’t know why I wanted to shoot you either.’ I wasn’t in the war there, but it was the same thing.”

The pair became good mates, and Gordon went to his funeral.

Now, more than 70 years after the end of the Second World War, Gordon likes to remember his mates and remains humble about his own involvement.

“I’m just an ordinary guy; just a nobody," he said.

"I sometimes joke that I'm living too long, and that's why I'm the only one left really, but it's worth it to be able to tell everyone about those days and the people I knew...

"We fought the war for people like you.”