The book that stopped a bullet

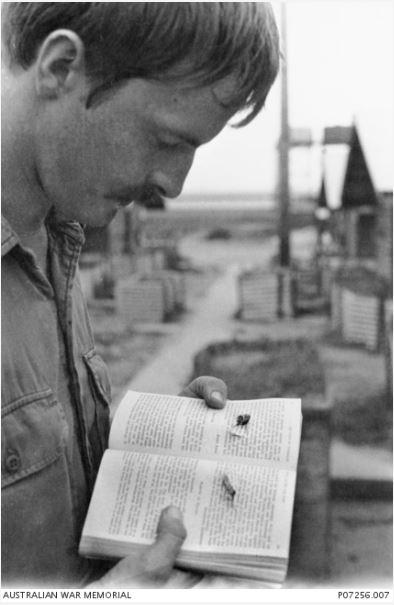

Second Lieutenant Graham David Spinkston with the book in Vietnam.

It was the book that stopped a bullet, but Graham Spinkston never actually got around to reading it.

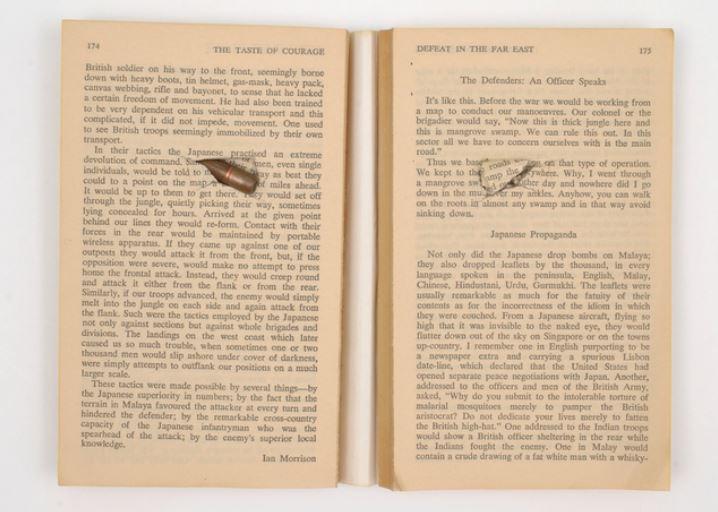

The book, The Taste of Courage, was in one of the army pouches around Spinkston’s waist when it was pierced by an AK47 round during the battle of Nui Le in Vietnam, and is now on display in the Australian War Memorial.

Forty-six years later, Spinkston still laughs when he’s asked about the book that caught the bullet meant for him.

“I never looked at it and I never read it,” Spinkston said on the anniversary of the battle. “Every five days in the jungle we’d be resupplied, and it just came out on a resupply and I grabbed it. I didn’t have time to read it. I just put it in my basic pouch and left it there for one day when I had a quiet moment and I could read it, but that day never came.

“Once I found the bullet in it, the CO said, ‘It’s going to the Memorial.’ That was the end of it, and I didn’t have a chance.”

Spinkston was in his early 20s when he went to Vietnam in May 1971. He’d been planning to become a geologist, but ended up joining the army instead.

“I was at university studying to be a geologist, but not very successfully,” he said with a laugh.

“I joined the Adelaide University regiment because it was a source of funds. I had no interest in the cadets at school, or anything like that, but when I joined the reserve, I found it was something that I really loved. I loved it so much I devoted way too much time to that, and I think to pubs and girls and to having a good time. So after two years, the university said: ‘We think you’d better go somewhere else.’”

Spinkston had already asked his parents for permission to join the army at the end of his first year at university. “Mum and Dad said, ‘No, you lazy little sod, go back to university and do it again,’ but after that second year they gave in and let me join the army,” he said.

“My dad was in the air force during the war, so he was probably a little peeved that I didn’t join the air force, but there was no way I was going to do that.”

Spinkston joined the army in July 1968 and went to officer cadet school at Portsea in Victoria. “That’s what I wanted to do and I loved it from the minute I got there.”

He was posted to Delta Company, 4RAR/NZ(ANZAC), and celebrated his birthday in the jungle a month after he arrived in Vietnam. “I got a birthday cake, and the platoon sang happy birthday to me - very quietly.”

On 21 September 1971, Second Lieutenant Spinkston was leading 12 Platoon in an area known as the Courtenay rubber plantation near the border of Phuoc Tuy province when they found themselves in a “major contact” involving B and D Companies.

“The day before 11 Platoon had a contact with some North Vietnamese, so we knew they were close,” Spinkston said.

“The next morning they reported they had found a track running through the jungle where a lot of people had walked, so we went towards there and found it. We were looking at it and we saw another little track running off into the jungle. I took my section commander, who was a corporal, and one of my scouts and a radio operator, and we went looking up this track to see what we could find, and all of a sudden all hell broke loose.

“They had a major bunker system just off this track and we hadn’t seen it … and then we came under a lot of small arms fire and a lot of RPGs were being fired into the trees to spread the shrapnel. Eventually we lost one of my soldiers [Private Jimmy Duff] and a number were wounded. We pulled back to call in fire support, and for most of that day we had artillery, helicopter gunships – both Australian and American – and at one stage I think we had about half the US Air Force in the air, offering to deliver all sorts of nasty things for us. I think it must have been a very quiet day in Vietnam that day, because everybody wanted to be where we were.

“That afternoon we attacked the bunker system. We didn’t make much progress because we were grossly outnumbered and they were dug in, so we eventually had to pull back.”

In what became known as the Battle of Nui Le, 24 soldiers were wounded and five were killed – they were the last Australians to die in combat in Vietnam.

“We recovered [Private Jimmy Duff] during the afternoon,” Spinkston said quietly. “A couple of guys in the section crawled up to where he was and brought him back, but the others had to be left overnight and were recovered the next morning.

“We withdrew to another spot and evacuated the wounded, which included me. That night, they were under fire all night, and that’s when [Second Lieutenant] Gary McKay [the commander of 11 Platoon, who received a Military Cross for his actions] was wounded. All the wounded were evacuated except for Gary because it was dark and they couldn’t do it.”

Spinkston later discovered that they had contacted bunkers, part of a larger complex occupied by an element of 3 Battalion, 33 NVA Regiment.

“It was incredibly noisy,” Spinkston said. “And you can’t see very far in the jungle, so all the time we were expecting them to come at us, but they didn’t. I guess because of the amount of fire support we were directing at them, they kept their heads down for a long time.”

Spinkston had been hit by shrapnel at 8.56 am. “Initially it was fine,” he said. “But it stiffened up during the day, and by the end of the day I could barely walk. I could have stayed, but the company commander said to me: ‘You’re bloody useless to me, go.’”

It was when he got out of hospital at the start of October that he found the bullet in the book.

“It was a surprise,” he said matter-of-factly. “I got all my gear back and I opened up the book and there was this bullet in it. It was as simple as that.

“It is scary, but we were so well trained, you know what to do and you do it instinctively. You’ve got no time to stop and think, ‘Shit, this is scary,’ until afterwards, and then you go, ‘Oh, that was a bit close.’

“When people are firing at you, if you can hear the bullets, it’s okay because they’ve already gone past. The ones that hit you, you don’t hear them because they get there before the sound does.”

Spinkston was a member of the last battalion to serve in Vietnam and had been there for ten months when they were sent home in March 1972.

When he was posted to Duntroon in 1978–79 as an infantry instructor, he found every cadet at the college had been to the Memorial to see his book. The bullet, however, is not in the Memorial.

“I confessed when I was there for a Portsea reunion last year,” he said with a laugh. “When I found out I was going to lose the book and the bullet I changed the bullet over and no one ever noticed. When the bullet’s fired, the rifle leaves swirling marks on the bullet, and no one ever noticed it wasn’t the real bullet, but I confessed last November.

“It’s my lucky bullet, and I’ve still got it. It’s on my key ring, and it’s been on my key ring ever since.”

But Spinkston nearly lost it in Qatar. “I forgot to put it in my luggage and I had it in my carry-on luggage,” he said. “This very zealous Qatari policeman said, ‘You’ve got a bullet.’ I said, ‘Yes, it’s a bullet, but it’s not going to hurt you or hurt anyone.’ ‘But it’s a bullet,’ he said.

“It took me an hour to convince him, and they allowed me to put my carry-on locked in the hold, so I’ve still got it. But that was nearly a disaster.”

The book The Taste of Courage was in Spinkston's basic pouch, just behind his hip, when it was pierced by a bullet.