'My nerves conjured up soldiers everywhere'

Lieutenant Colonel John Eldred Mott MC and Bar.

After John Mott was captured at Bullecourt in April 1917, he was determined to escape.

He wrote a hidden message in saliva in a letter to his brother and became the first Australian officer to successfully escape from captivity in Germany during the First World War, travelling more than 130 kilometres through enemy territory to safety.

More than 100 years later, the letter is part of the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

For Research Centre curator Jennie Norberry, the letter is a poignant reminder of Mott’s story of bravery, daring and luck.

Born in country Victoria, Mott enlisted in August 1915 at the age of 38. He was severely wounded in the neck during the fighting at Bullecourt in April 1917 and survived alone for three days in the bottom of a trench before he was discovered by the Germans. He was taken prisoner and eventually sent to the British officers’ camp at Ströhen in Germany.

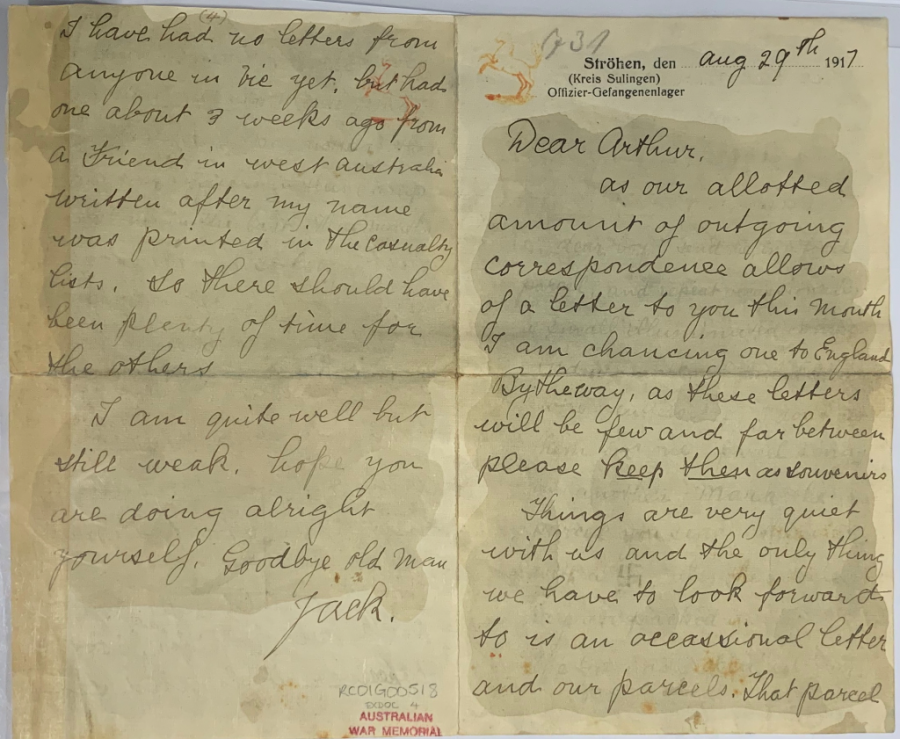

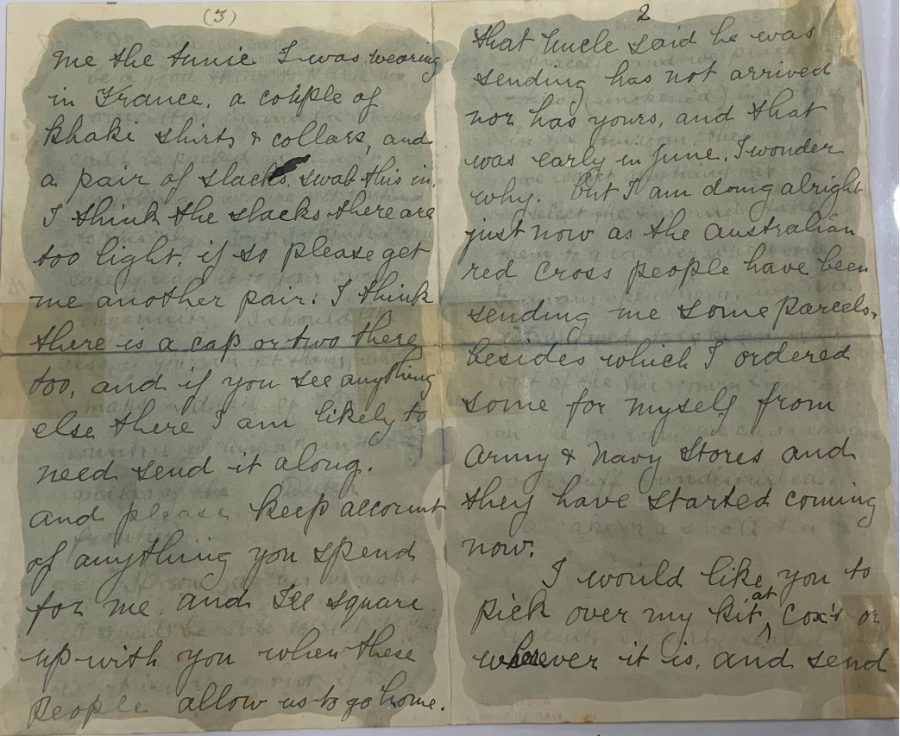

“We have a letter that he wrote to his brother while he was in captivity,” Norberry said.

“When it was donated, he explained that he had inscribed an invisible message to his brother asking for materials for the escape.

“It was achieved by writing with a new writing nib dipped in saliva, and then his brother Arthur knew to go apply a diluted solution of ordinary ink over the page to bring the message out … You can see where the wash has been applied over the top of it.”

John Mott wrote a hidden message in this letter to his brother Arthur.

The letter was addressed to Lieutenant Arthur Mott, of the Australian Flying Corps, and was sufficiently innocuous to pass the German censors.

“Dear Boy,” Mott wrote in his hidden message. “Send me in a food parcel … a small illuminated compass and a small light but efficient wire-cutter. If I don't get them in one parcel I may in another.”

He asked his brother to mark the parcels with a special symbol, as well as the articles the items were packed in, so that he would know where the materials were hidden.

“A cake or small tin of biscuits properly sealed would be a good thing to pack the wire-cutters in and the compass could be packed in almost anything,” he wrote. “We are not confined to tins only but I think I can safely leave it to your ingenuity.”

A signed studio portrait of Lieutenant Henry Chester Fitzgerald, left, and Lieutenant Colonel John Eldred Mott MC and Bar (later Lieutenant Colonel), the first Australian officer to escape from captivity in Germany.

On the night of 26 September 1917, Mott and another Australian, Lieutenant Henry Fitzgerald, crept out of the barracks and used a key Mott had fashioned from a piece of steel plating to unlock the gate, all without rousing the suspicions of the sentries.

For the next six days, Mott made his way towards the Dutch border, avoiding roads and resting in the woods during the day to avoid detection.

"We were twice almost recaptured,” he wrote. “And our chance of escape seemed a million to one against.”

On the fifth night, disaster struck.

"Packing our wet clothes, boots and food on our backs in the darkness, we jumped into the icy water,” Mott wrote. “Half-way across we heard the cry 'Halt,' but did not heed it.”

Informal portrait of Captain John Eldred Mott MC and Bar (later Lieutenant Colonel), the first Australian officer to escape from captivity in Germany, taken the morning after he reached Holland. Captain Mott is wearing the clothes in which he escaped. The fence in the background is the dividing line between freedom and captivity.

They had been spotted by a German bicycle patrol as they prepared to cross the Ems River near Schüttorf. Fitzgerald was recaptured, but Mott managed to outrun the patrol.

“Having wrung out my clothes, I set off downheartedly through the lonely forest,” Mott wrote.

“Shivering with cold, I stumbled in the blackness of the forest for two hours till I came to a sheet of water 250 yards wide. It was hopeless for me to try to swim it as I was weak from my wounds, which had not healed …

“I sat on the bank like a great kid, downhearted. After a rest I explored and found a narrow stretch ... My boots, which were on my back, floated off, but I recovered them [and] in trying to replace them I sank, and was nearly drowned …

“At last I reached the bank, and caught the branch of a tree … I found that I was on an island, with another wide stretch of green, slime covered water ahead ..

"Hopelessly I walked into the water but found it shallow, and waded through it to the other bank … felt that I was walking on air, for [I] knew this to be the last of the rivers.”

He was just three miles from the border.

“I stood all day swinging my arms and stamping my feet to minimise the cold and to help me forget my hunger,” he wrote. “I took off my boots and crept the last two miles, stopping and watching for sentries, thinking that every bush was enemy.”

He eventually slipped past the German sentries and bloodhounds, negotiated an electrified fence and crossed into the Netherlands on 26 September 1917.

Mott rejoined the 48 Battalion in the field the following year and received a Military Cross for his actions on 8 August 1918. He received a bar for his escape from captivity and ended the war as a lieutenant colonel. He died in England in 1933.

Claire Hunter is a writer for the Australian War Memorial.

The Memorial is temporarily closed to the public, but the Memorial is still telling stories about the Australian experience of war. To learn more visit www.awm.gov.au/visit/museum-at-home

There will be a nationally televised Anzac Day commemorative service on 25 April 2020 which will be closed to the public. The ABC coverage will begin at 5.00 am with the service starting at 5.30 am. It will also be streamed live online.