'Hell would be a pleasure resort'

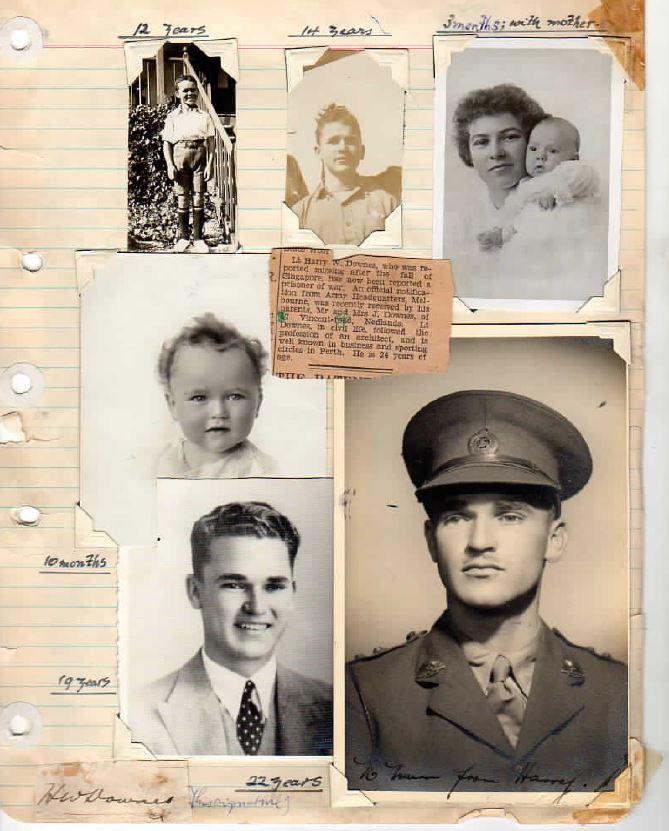

Harry Wraith Downes. Photo: Courtesy Estelle Blackburn

Estelle Blackburn never got to meet her uncle, Lieutenant Harry Wraith Downes. He died before she was born, but his story as a prisoner of war on the infamous Burma–Thailand Railway has been a constant presence in her life.

“Harry was very much a part of the family,” Estelle said.

“His architecture medal was on the mantel piece … and he was always talked about and very much missed.

“Red roses were his favourite flowers, and whenever mum saw a red rose in an unusual place, she always took that as a message from Harry … so Harry was always there, and was always very much with us, and a part of us.”

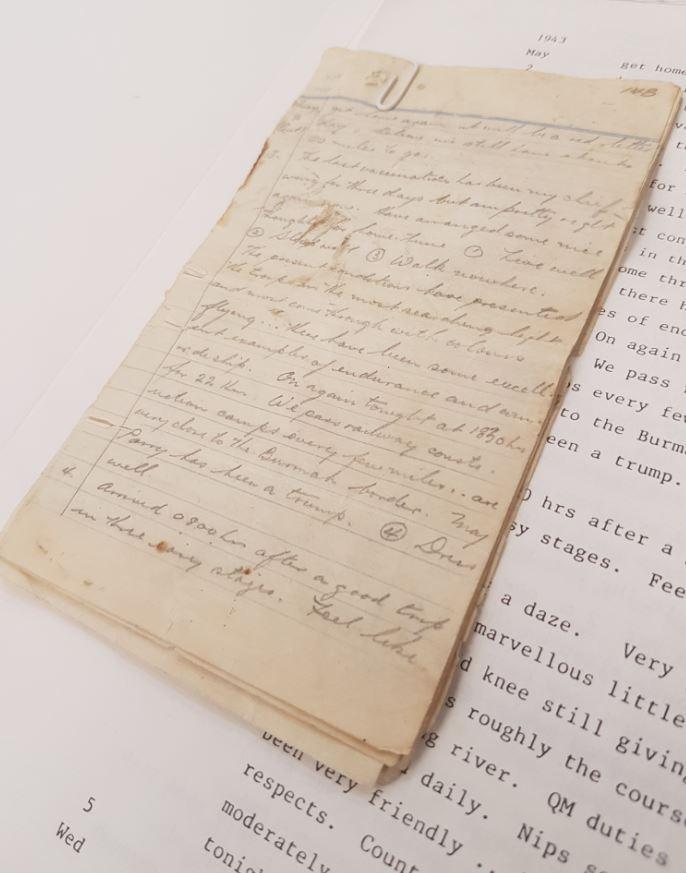

Her family treasured Harry’s letters and the neatly written pages of the diary that he kept secret from his captors during the Second World War. The diary was saved by Harry’s batman Noel Hellmrich, who risked his life to hide it, and gave it to Harry’s family the day after he returned from the war. The diary, which details the harrowing experiences of Harry’s life as a prisoner of war under the Japanese, is now part of the national collection at the Australian War Memorial.

“The officers burnt most of his diary [after he died for security], and his batman only managed to save a bit of it,” Estelle said.

“Amazingly, my mother lost it at one point, and it was found on a freeway in Perth. Whoever found it managed to find mum and get it back to her, so that was a lovely little rescue there.”

Described as a “brilliant and serious young man” with “a keen sense of humour”, Harry Wraith Downes was born in 1918. He was named Harry after his two uncles who were fighting on the Western Front in France when he was born. His father often called him “Digger”, or “Dig”, in honour of the Australian diggers who had fought during the war, including a member of their extended family who had been killed on Gallipoli.

Harry Wraith Downes, centre, with his sister Margaret and his brother Jim. Photo: Courtesy Estelle Blackburn

When the Second World War broke out, Harry was determined to enlist.

An award-winning Perth architect full of promise, he joined the Royal Australian Engineers 2/6 Field Park Company and embarked for Singapore with other reinforcements in January 1942.

A month later, Singapore fell to Japanese forces and Harry was one of the thousands of Allied soldiers who were taken prisoner and sent to the Changi prisoner of war camp.

But worse was yet to come.

In April 1943, Harry was attached to a labour group of Australian and British prisoners of war known as F Force, and was sent to work on the notorious Burma–Thailand railway.

Conditions for the prisoners were extremely harsh; the men were over-worked, underfed and poorly treated. Disease and malnutrition were rife, and men died in their thousands.

“It was a ghastly start,” Estelle said. “They were loaded into these very hot, sweltering, crammed railway carriages and let out at Bampong railway station. From there, they had to march the rest of the way … marching 20-25 kilometres each night to Kanchanaburi and on to further camps...

“[They] were starved, beaten and forced to continue the backbreaking work when thin and weak from only nine-10 ounces of rice a day – later dwindling to half that – and sick from the tropical diseases they were so prone to in the hot steamy conditions so different from home.”

Harry carefully recorded the deaths of his mates and the numbers suffering cholera, dysentery, malaria and diphtheria in his diary.

“Hell would be a pleasure resort,” he wrote, while noting that he could see almost every bone in his body.

Once, he even wrote how nice the rice broth was; it was just rice and salt, but he recorded out how exciting it was to find some yak bones in the stew, and once three shreds of yak meat.

“Agony sessions, or talk about food is our main topic of conversations these days,” he wrote. “Visions of toast or sponge cake, fig jam and clotted cream for the last three days.”

Harry Wraith Downes. His father wrote about him in the family tree. Image: Courtesy Estelle Blackburn

Despite the starvation and cruelty he endured at the hands of the Japanese, Harry still managed to find a connection with two of his captors, noting on 14 June that he had enjoyed an “interesting talk with two Nip architects”.

Architecture had been Harry’s great love before the war.

From the time he could sit up in his high chair and say “more”, Harry had been interested in drawing and his flair for sketching soon became evident.

At the age of 14, he won an architectural drawing competition to design an extension for the local RSL in Collie in the south-west of Western Australia. It would be the first of many successes for the brilliant young architect.

Just before he turned 18, Harry began training and working with Harold Boas, of the prominent Perth architectural firm Oldham, Boas and Ednie-Brown, and passed his exams to become a registered architect before his 21st birthday.

He won the prestigious Eustace Cohen Bronze Medal of the Western Australian Institute of Architects in 1937, and Harold Boar was planning to offer him a partnership when he returned from the war.

But it was not to be.

The pages of Harry's diary provide an insight into his life as a prisoner of war.

Eventually poor diet, constant marching, and the inhospitable conditions took their toll and Harry was taken to a camp hospital at Nieke in Thailand.

On 23 July 1943, Harry was reported to be suffering from the symptoms of cerebral malaria, which rendered him delirious. Despite being given sedatives and being looked after by his fellow patients, Harry escaped from the hospital during the night and, in his delirium, Harry wandered off into the thick jungle towards the swollen River Kwai.

A number of search parties were sent out around the camp, and they tried desperately to find him, but it was impossible to follow his tracks because of the heavy rain.

“It will never be known whether he was trying to get to the latrines in the deep mud and slipped or was so disoriented he just fell into the River Kwai,” Estelle said.

“When he died the water would have just been rampaging, and I think in his delirium he would have just slipped and fell, but we’ll never know.

“His batman wanted to stay with him that night, but the English doctor said, ‘No, he’ll be alright.’ If he’d had his batman there with him, he might not have wandered off, but nobody knows what actually happened.”

Harry's batman Noel Hellmrich. Photo: Courtesy Estelle Blackburn

Harry’s body was never found, though the Japanese reported that his body was seen caught in bushes at Tamaranpat, more than 50 kilometres downstream. They reported that an attempt was made to retrieve his body, but it was quickly swept away, and was never seen again.

One of Harry’s friends, a British officer, later wrote: “He certainly had a lot of courage. All the officers and men in the camp were shocked [by his death] as he was highly respected by everybody. Harry was a brave and unselfish officer and I was proud to know him.”

Harry had been equally proud of his men. “These conditions have presented the troops in the most searching light and most come through with colours flying,” he noted in his diary. “There have been some excellent examples of endurance and comradeship.”

The diary ends just days before he died. Virtually his last note was that there were only 76 fit men out of 1,021 in the camp.

The night that Harry died, his mother woke up in Perth, and made a note the next morning that said simply: “Harry came to my bedside last night.” Several kilometres away, one of her sisters did the same.

Harry Wraith Downes pictured during training in Western Australia. His image is marked with an X. Photo: Courtesy Estelle Blackburn

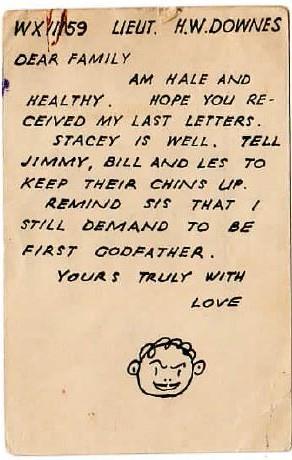

“Letters had stopped, cards had stopped, and … they feared the worst … but his family was not officially informed of his death until the war ended two years later,” Estelle said.

“My brother Greg and I remember our mother telling us of Grandpa drawing the family together after dinner to give them the sad news that Harry wasn’t coming home, ending the hope they had maintained.

“We weren’t allowed to buy anything Japanese for Grandma or use the pencils Uncle Harry sharpened for her before he left… They remained in a box, untouched, and I would occasionally open them and look at ‘Uncle Harry’s pencils’.

“Mum cried when I asked her to teach me Waltzing Matilda before I left for a working holiday in Europe … and I was washing the dishes with her the night before the flight, and I said, “Can you teach me the words to Waltzing Matilda?’ She burst into tears … and through her tears she told me Harry had asked her the same just before he left.”

A postcard Harry sent home. Image: Courtesy Estelle Blackburn

Last year, Estelle made a pilgrimage to the Burma–Thailand railway to follow in her uncle’s footsteps and learn of what he had endured during the Second World War. As an award-winning journalist based in Canberra, Estelle was moved to find a memorial plaque overlooking the camp where her uncle died, which had been placed there by former employees of the Snowy Mountain Engineering Corporation.

“I was touched that these workers from so close to home had thought to pay tribute to the prisoners of war and other railway workers who had suffered the brutal conditions and died there, so far from home,” Estelle said.

Her guides went out of their way to find a boatman to take her down the lake so that she could float over where the Nieke camp had been, and then walk a little way along the railway line.

“I threw in a poppy and a frangipani … and the whole thing was very moving,” she said. “To top it off, [they] presented me with a railway spike; what a special souvenir of Uncle Harry, and an emotional trip to remember him.”

Today, Harry's kit box takes pride of place in her lounge room, and one of his great-great-great nephews is named after him.

His life was commemorated in a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial on the weekend of what would have been his 101st birthday. Estelle had received the news of when the ceremony would take place on the day that he would have turned 100.

“For Uncle Harry, it really is his funeral,” she said. “It means so much … with three generations of his family coming from Albany, Perth, Brisbane, Hobart and Sydney …

“He’s finally got a funeral … at long last.”

Lieutenant Harry Wraith Downes’ life was commemorated in a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial. His diary is held in the national collection, and his uncle, Lieutenant Harry Downes MC MM, is pictured in the First World War galleries.