Australia and its screw

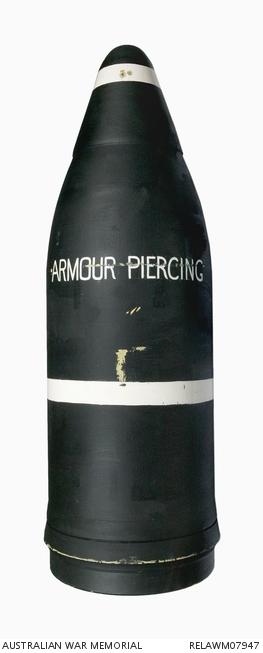

In the grounds of the Memorial, between the main building and Anzac Hall, visitors can find one of the propellers of the first HMAS Australia. The outer port side (left, when looking forward on the ship) screw to be precise.

Large ships’ screws are marvels of mechanical, metallurgical, and mathematical engineering. These were built to transmit well over 10,000 shaft horsepower from the engines to the dark sea. Modern ship screw designs are often the subject of intense national security efforts.

It’s an interesting artefact at first glance, but scratch the surface of its history and it becomes even more fascinating.

What’s the difference between a screw and a propeller?

Not much. All screws are propellers, but not all propellers are screws. Generally speaking on ships (which often have aircraft propellers as well as the ones that move the ship), the distinction is made that the screws are part of the ship and the propellers are part of the planes or helicopters.

The ship

HMAS Australia (I) was Australia’s first and only capital ship. It was built under a plan for each of the Imperial Dominions to create a fleet of cruisers and destroyers with a fast battle-cruiser at its heart to assist the Royal Navy in policing the world’s oceans. She was funded by a national campaign of fundraising, cake-bakes and lamington drives which was so successful that when the ship was purchased there was money left over. That funded the clock tower at the Royal Australian Naval College at Jervis Bay, NSW. The clock tower overlooks the parade ground to this day.

The ship made a huge impact when she arrived in Australia in 1913 and the event marked the creation of the Royal Australian Navy.

The Hobart Mercury had this to say on 20 December 1913 when she came to visit in the Derwent:

“... in reality modern battleships are hideous things. The beauty is all below the water line; there is certainly none within sight. Battleships grow uglier as they become more deadly, which is as it should be. There is nothing deceitful about them. They look the awful brutes they are. Nelson's ships were things of beauty. The Australia will be voted the most evil-seeming monster the people of the Commonwealth will have set eyes upon. But brutal as she looks, she does not suggest her full capacity for devilry. You can't believe in the range and power of her sleek, pugnacious guns. It is incredible that her speed is faster than that of the average Australian train. Every part of the fighting monster, from guns which each fire half a ton of shell, to the secluded magazine, where Death's "visiting cards" are stored, fills an observer with wonder of human achievement.”

A sense of the 12-inch guns can be had from the video of scenes on board HMAS Australia in the Memorial collection. www.awm.gov.au/collection/F00060/

Australia at war

HMAS Australia had a moderately successful start to the war. The threat of her 12-inch guns, which had such an effect on the Hobart Mercury, also encouraged the German forces in the South Pacific to surrender or flee.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes said:

"but for the Australia …the great cities of Australia would have been reduced to ruins, overseas trade paralysed, coastwise shipping sunk, and communications with the outside world cut off."

The South Pacific secured, she was sent to join the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet facing the German High Seas Fleet across the North Sea.

There misfortune of a sort struck.

Repeatedly running into New Zealand

Trevor Ross served in the RAN for 38 years and resigned as a Captain having served on both HMAS Australia (I) and her namesake, the heavy cruiser which fought in the Second World War, HMAS Australia (II).

In 1975 the Naval Historical Review published his firsthand recollections which are well worth a read if you want more detail than can be provided in this article.

On 21 April 1916 when patrolling the North Sea HMAS Australia and HMS New Zealand were steaming abreast when they entered a fog bank at the same time as they were ordered to zig-zag.

Australia zigged, New Zealand zagged, and the two ships came together in the fog, causing significant damage. As the ships parted New Zealand’s port outer propeller chopped into Australia’s hull, further damaging Australia and destroying New Zealand’s propeller.

New Zealand then tried to pull away from the collision. But without power on the port side it was like a kayaker paddling with only one paddle, turning her back around across Australia’s bows to collide again.

When the fog cleared New Zealand was gone, returning to Rosyth in Scotland for repairs while Australia had to take some time assessing the damage before getting underway.

Repairs and a replacement screw

By the time Australia made it to Rosyth the two dry-docks were full, one of the spaces taken by New Zealand.

The damaged Australia made its way to Newcastle-on-Tyne where a gale, too strong for the tugboats manoeuvring her into harbour, forced her to collide again, breaking both the port propellers and bending the port rudder.

(Readers might recall that the propeller here at the Memorial is the outer port one.)

Ships screws are made specifically for a particular ship. At the time of construction spares are made. In Rosyth, New Zealand had commandeered Australia’s spare screws to repair its own damage.

Australia was moved on to Devonport and was sent two more screws from other Royal Navy ships. The port outer screw was replaced with one made for HMS Indefatigable.

The screw at the Memorial is likely the one originally made for HMS Indefatigable.

The destruction avoided

Australia put to sea on 31 May 1916 with Indefatigable’s screw. The same day the British ship would meet its end in the major naval battle of the war.

In the battle of Jutland, HMS Indefatigable suffered a magazine explosion and went down. Of her crew of 1,019, only three survived.

Three battle-cruisers of similar design to HMAS Australia exploded that day with very few survivors.

Having missed the battle, Australia by chance ended up rendezvousing with the battered fleet as it returned to base at Scapa Flow. Ross described the scene.

"We went west about round Ireland and arrived at Scapa on 3rd June, steaming in with other ships of the Battle Cruiser Fleet to the ringing of cheers of the Battle Fleet – you can imagine our feelings."

Lost and then found

Between the enormous cost of operating such a large ship, the arms limitations of the Washington Naval Treaty, and the fact production of her ammunition had ended, the decision was made to scuttle HMAS Australia off Sydney Heads in 1924.

There had been some suggestions she should be used as the national war memorial, which would have made for a very different Australian War Memorial today.

Her exact location was then unknown for over 80 years.

In 1990 a company surveying for an undersea cable found a large unknown shipwreck. It wasn’t until 2007 when the New South Wales Heritage Office was able to borrow a United States Navy deep sea remote operated vehicle (ROV), the the wreck was confirmed as being the first HMAS Australia.

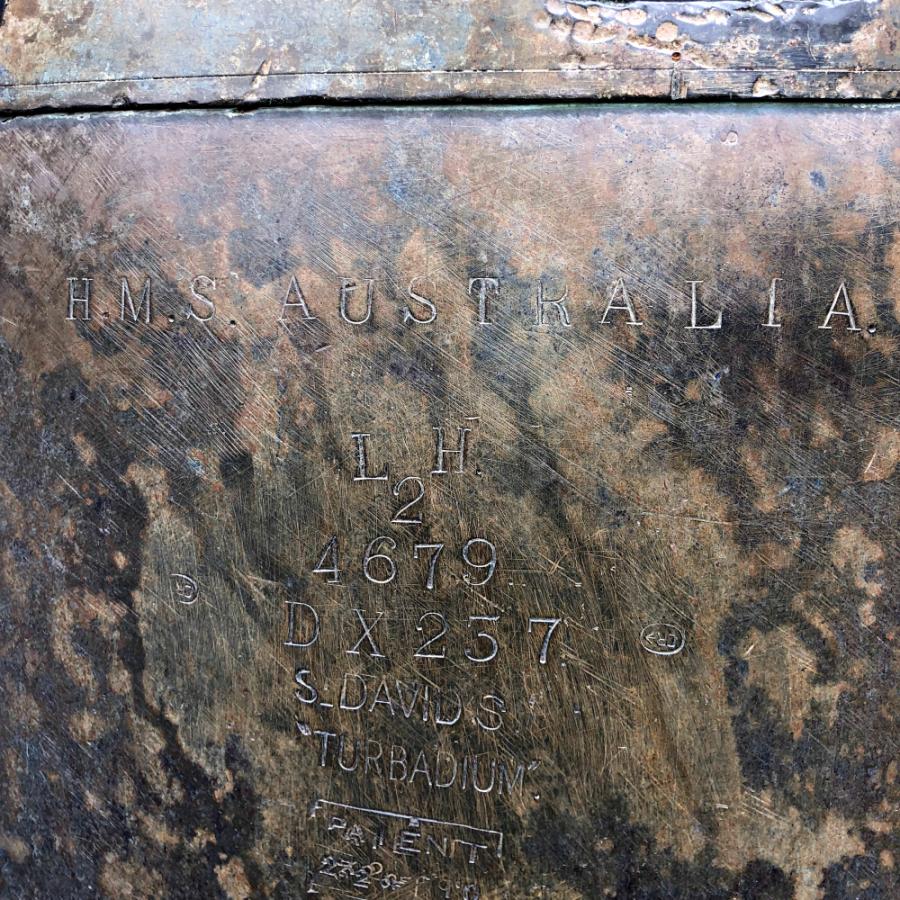

The Inscription

The screw does have an inscription engraved on it.

This inscription presents a bit of a mystery as at no time was the ship known as “HMS Australia” (as opposed to “HMAS Australia”) and it’s not clear if it was added when the screw was made, or later.

If anyone knows more about the history of this object we’d love to hear about it!

Further Reading:

The Hobart Mercury on the arrival of HMAS Australia: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/10311404

Trevor Ross’s account of the collision: https://www.navyhistory.org.au/battle-cruisers-in-collision/

More on Trevor Ross’s service: https://www.navyhistory.org.au/a-naval-encounter/

Environment NSW’s report on the wreck of HMAS Australia: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/MaritimeHeritage/whatsnew/index.htm#hmasaustraliashipwreckreport