Remembering Duncan John Murchison and HMAS Canberra

Flight Lieutenant Duncan John Murchison.

When Robyn Gladwin was growing up, her mother Marjorie wouldn’t talk to her much about her father, Flight Lieutenant Duncan John Murchison. But she always told her daughter that she knew the exact moment he was killed during the Second World War when Robyn was just a newborn baby.

“She was still in the hospital in north Sydney,” Robyn said as she shared her family’s story.

“She could remember seeing the photograph of him on the dressing table in the room suddenly fall over, and she called for one of the nurses, and she said, ‘Sister, my husband’s been killed.’ The Sister said, ‘No, you just settle down.’”

It was 75 years ago on 9 August 1942 and Robyn was just six days old. Her father had been killed on HMAS Canberra when it was attacked in the early hours of the morning by a group of Japanese cruisers and a destroyer in what became known as the battle of Savo Island.

“My mother’s hair, with the shock of it, went white,” Robyn said.

“She was later told that they knew [on the ship] that I had arrived, that a message had come through that he’d had a baby daughter and that they toasted me in cold tea.

“I was only six days old when he was killed and I can only tell you about my father because of my close relationship with my grandparents. As a child, he was to me, Daddy Duncan, the picture on my grandmother’s piano.”

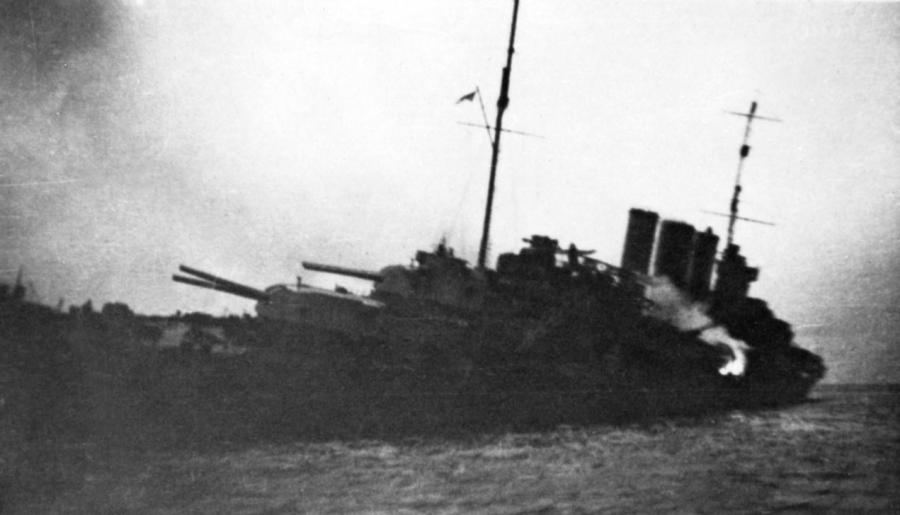

HMAS Canberra sinking following the battle of Savo Island.

Duncan John Murchison was born on 20 January 1916 in Melbourne, the son of Finlay and Fanny Louise Murchison, and at the age of three had a great adventure, sailing to London via Cape Horn with his seafaring parents and spending time in Britain after the First World War. By the time he met Robyn’s mother, Marjorie Ferguson, while working together in Sydney in the late 1930s, the pair found they had much in common – they were both only children and their fathers were both sea-pilots who had served for many years on the pilot steamers of Sydney and Newcastle.

“They both worked for the National Mutual Life Insurance Company, and Mum said she could remember meeting my father,” Robyn said, smiling as she remembers the story. “She’d seen him in the distance and thought he was pretty nice looking, and both her father and my father’s father were Sydney pilots and they brought the ships in. They were both master mariners, and she said she could remember my father walking up and saying, ‘Hello, I’m Captain Murchison’s son.’ And she thought, ‘Well, you arrogant fellow.’ She said, ‘Well, you’re speaking to Captain Ferguson’s daughter.’ And that’s how they met.”

When war broke out, Duncan enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force on 4 March 1940 at Mascot in Sydney, serving first as an air cadet, then from August 1940 as a pilot officer.

“My mother, and my grandparents particularly, used to say – because my grandfather was a seafarer – my father said when war broke out, ‘Don’t think I’m going to join the Navy. And I’m not going in the Army because I don’t want to march around. I’m going to fly.’ So he joined the RAAF and he trained at Point Cook in Melbourne.”

Duncan and Marjorie were wed the same year. “They married in St Stephen’s Presbyterian Church in Macquarie Street in Sydney,” Robyn said. “And there were so many weddings that day because of the war that they were married that day at 8 o’clock at night.”

To celebrate the union, Robyn’s grandfather said he’d give the couple some money towards their house or towards the wedding as a gift. “My mother said they’d use the money for their house,” Robyn said. “But my father said, ‘No, we’ll use the money for the wedding so that if something happens to me, you’ll have at least had a proper wedding and something to remember.’

“And my father evidently didn’t want a child. He said, ‘Look, if something happens to me, you’ll be left with a child.’ And she said, ‘No, it would leave me with a little piece of you.’ And that’s why I’m here.”

Duncan was due go to Canada at the time for air training, but a fellow airman said Duncan couldn’t go because he was being married that day, and the other fellow went instead in his place. The airman was killed in an aircraft accident in Canada, so the newly married couple decided they would name their child Ronald after him if it was a boy or use the first two letters of his name if it was a girl.

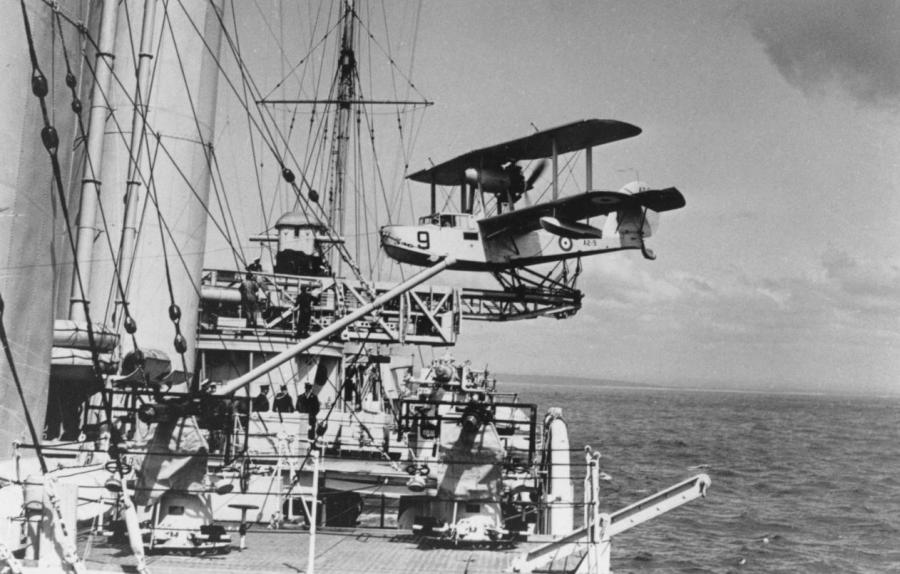

An RAN Supermarine Seagull V amphibian aircraft prepared for take-off from its catapult onboard HMAS Canberra. The number 9 on the nose signified it was on detachment from 9 (Fleet Cooperation) Squadron RAAF which carried out this ship-borne role.

Duncan joined 9 Squadron in December 1940 and served with them on HMAS Canberra doing air reconnaissance, anti-submarine activity, and artillery spotting. Known as a talented and reliable pilot, he flew Supermarine Seagull aircraft which launched from the ship’s deck with the use of a catapult, and on returning from their mission, landed on water.

“Flying Officer Murchison is a particularly good type, and above average as a Naval co-operation pilot,” an officer wrote while recommending him for a promotion in March 1942. “He has a pleasing personality and is popular in all company. He is loyal, tactful and keeps himself physically fit.”

The officer added that Duncan was “considered by the Navy to be their best Air Force officer and naval co-operation pilot” and Duncan was promoted once more, this time to the rank of Flight Lieutenant on 1 April 1942.

A Supermarine Seagull V amphibian aircraft from HMAS Canberra.

The last night Robyn's mother ever saw Duncan was the night of the Japanese midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour at the end of May.

“He left from there and she didn’t ever see him again,” Robyn said. “Before that, I don’t know what the timing was, she got a telegram saying be at Mascot Airport at whatever time it was, and a group of the wives had been selected to go and see them when they were in Melbourne. She said she was sure the plane they flew on was put together with sticky tape and it was the most nerve wracking flight of her life.”

Duncan was aboard HMAS Canberra when it came under heavy Japanese attack from seven cruisers and a destroyer just before 2 am on 9 August while supporting US Marines near Savo Island in the Pacific. As the lead ship, Canberra received the full force of the Japanese barrage. The ship was hit 24 times in less than two minutes, and 84 of her crew were killed, including Captain Frank E. Getting, who was mortally wounded in the battle and died later.

In his account of Canberra’s loss, Stoker John Oliver Rosynski describes the Japanese ships approaching Canberra and the chaos that ensued, recounting how Getting stood on the bridge, slowly and calmly giving orders.

“It seems some power, some unknown devil steered the old ‘Canberra’ through thick and thin for nearly three years, then it let us have it all at once,” he later wrote. “She never had a chance.”

Below decks, as enemy shells exploded, damage control crews vainly fought the fires and the ship’s medical parties were forced to tend their charges in darkness. Insufferable heat caused the sickbay to be evacuated as the order came to prepare to abandon ship and the wounded lay in pouring rain, covered as much as possible by coats and blankets.

“I spoke to the Captain but he refused any attention at all,” the surgeon later wrote. “He told me to look after the others.”

In the darkness and confusion, the attackers wreaked havoc before withdrawing, and Duncan was one of the many reported missing, presumed dead as the ship was abandoned. The next day, USS Selfridge fired 263 5-inch shells and four torpedoes into Canberra. But the stubborn Canberra refused to sink until a torpedo fired by the USS Ellet administered the final blow. Canberra sank at about 8 am on 9 August 1942.

The US Navy Baltimore Class cruiser USS Canberra was later named in her honour, the only American warship named for a foreign warship or a foreign capital city.

Duncan’s death was officially confirmed in March 1943. He was just 26 years old. A couple of the survivors kept in touch with Duncan’s parents for the rest of their lives and the priest on the ship, Father Bill Evans, visited Duncan’s widow in hospital.

“He had my father’s overcoat, which had been put over one of the survivors in the lifeboat,” Robyn said. “And I remember her saying to me, ‘It even had a dirty handkerchief in it.’”

Father Evans, who later built a church as a memorial to the victims, became a life-long friend, ministering over Robyn's first marriage ceremony in the 1960s.

The captain’s widow also visited after the disaster, giving Robyn's mother a special Bunnykins china bowl for her baby that she treasured until the day she died in 1990. When Robyn visited her mother just a few months before she died, she hoped to find out more about the Canberra and her father, but it was still far too painful for her mother to talk about.

“She was lying there and I said, ‘Tell me about my dad. What sort of a guy was he?’ And she said, ‘Robyn, he was not a guy.’ And the shutter came down and she couldn’t talk,” Robyn said.

“I thought that would have been a really good time to find out, but nope, she couldn’t do it … I’ve got a real gap in my life. And I often think, what would my life have been like if my father hadn’t died.”