Indigenous Soldiers of the First World War and the Stolen Generation

In 1914 the Australian government placed a call for volunteers to fight a predominantly European war in the interests of the British Empire. Indigenous Australians answered that call in numbers. In doing so, they faced challenges other Australian volunteers did not.

At the time, the Defence Act exempted those “not substantially of European origin or descent” from enlistment. Although not explicitly identifying Indigenous men as excluded from service, advice in a military recruiting handbook from 1914 clarified the position, stating, “Aborigines and half-castes are not to be enlisted. This restriction is to be interpreted as applying to all coloured men.” Despite this, many Indigenous men were accepted for enlistment. By 1917, dwindling enlistments and a need for reinforcements at the front led to a watering down of these rules and recruiters could then accept men who could satisfy a medical officer that they had “one parent of European origin”.

Once they enlisted, Indigenous soldiers from New South Wales were faced with a greater risk of having their children removed by government intervention. Powers acquired under the NSW Aboriginal Protection Act 1915 enabled the Aboriginal Protection Board to remove Indigenous children without parental approval or knowledge.

In 1915, as troop ships sailed from Australia to the European theatre carrying numbers of Indigenous volunteers, the Board was handed these expanded powers to separate Indigenous children from their families without the need to prove in court that the child was neglected. Without the protection of natural justice, children of serving Indigenous soldiers were more vulnerable than ever to be removed from their communities to become part of the Stolen Generation.

William Francis was one Indigenous man among many who enlisted for service in the First World War. In March 1917 he left a good job with the NSW Railways to sign up for overseas service at the Singleton recruitment office. He altered his name to “Frances” and claimed to be of New Zealand birth, which was a well-recognised strategy for successful enlistment. Francis was actually a 43 year old Indigenous father of three boys, two of whom were dependent children, with deep ties to Singleton.

In his youth, Francis had worked as a farm labourer, spending time on the Paterson River property “Lemon Grove”, which was owned by the Swan family, well known pioneers of the Hunter Valley. Francis sometimes went by the name “Billy Swan” in Singleton, where he was well known as having a close association to the Singleton Mission Home and the missionaries who oversaw its operation. In 1905, Retta Dixon had founded the Mission Home and Singleton Aboriginal Children's Home which educated and cared for several children from the local Wonnarua Nation.

Singleton Mission Home c. 1908. State Library of New South Wales

Having successfully enlisted, “Private Frances” embarked a troopship in Sydney in May 1917 and arrived two months later in England. By mid-November he had been allocated to the 36th Battalion and had arrived on the Western Front to replenish the troop numbers lost in battles in the Ypres Sector.

When the German Army launched its last great offensive in the spring of 1918, Francis’ battalion was deployed to defend the village of Villers-Bretonneaux in France. On 26 April 1918, the 36th Battalion was gassed, and Francis and others were sent through casualty clearing stations and convalescent depots until he arrived at the French coast for rehabilitation.

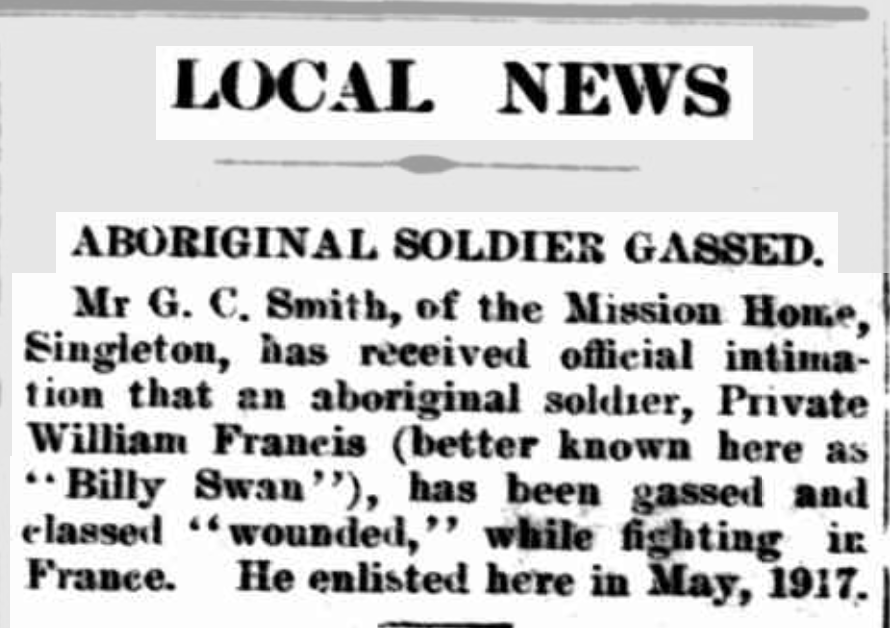

The local paper in Singleton reported, “Mr G.C. Smith, of the Mission Home, Singleton, has received official intimation that an aboriginal soldier, Private William Francis (better known here as ‘Billy Swan’), has been gassed and classed ‘wounded’, while fighting in France.”

Singleton Argus, 25 June 1918

As Francis and his comrades recovered, the depleted 36th Battalion was disbanded in order to reinforce other units. Francis was allotted to the 34th Battalion, and returned to active duty in August 1918, as his new battalion was deployed to defend the approach to Amiens. Amid fierce fighting, Frances was wounded on 26 August. Having been seen by a field hospital, he was again sent behind the lines to the Australian Convalescent Hospital at Le Havre.

Released back to his unit five days after the Armistice, William Francis was eventually discharged on his return to Australia in August 1919. Twice wounded in action, he had been involved in climactic battles that resisted the final German assault before securing allied victory. Francis had proved his worth and equality to his fellow soldiers and Australians, and he had pushed back the black boundaries for Indigenous Australians.

Yet, while Francis was fighting, a new regime had swept through Singleton, altering all that was valued by him. The Mission Home had been taken over by the Aborigines Protection Board, which had legislative powers over all Aboriginal children in New South Wales. From 1918 it was used by this Board as an institution for children who had been removed from Aboriginal stations and reserves under the Aborigines Protection Act 1909.

Following this mandate, the Aborigines Protection Board began to place children in the Singleton Aboriginal Children's Home, and took an interest in the children already there, including Francis’ sons, Arthur and Eric. Francis had placed his boys in the home to be cared for by the missionaries, George Colton Smith and his wife Jenny, and to be educated while he was absent with work and war service. He held a deep trust in these missionaries, which is evidenced by his AIF will, which left all his possessions to the Singleton Children’s Home. Arthur and Eric had entered the Singleton Mission Home in 1911, having come “from the Aboriginal Reserve at Mt Olive, also known as St Clair, just outside Singleton – under the care of Aboriginal Inland Mission”.

In February 1918, Arthur, then 14 years old, was removed from the Mission Home by the Aborigines Protection Board, separated from his brother and placed under control of the State Children’s Relief Board as a State Ward. Arthur spent three months at the State Farm Home at Mittagong while Eric remained at the Singleton Mission Home. In May, Arthur returned to the Mission Home and Eric was sent to the Children’s Board Depot at Oxford Street in Paddington with instructions for his mother not to be given his address.

William Francis returned from the First World War in August 1919 to find his children had been taken away. It was a deep betrayal by the government he had just fought for. Whatever measure of equality he had found in the trenches of the Western Front, it would not be found in his homeland.

There is little doubt that Francis suffered trauma following the intensity of frontline fighting, then returning to discover his children and the reserves and missions had been taken over by the Aborigines Protection Board. He became increasingly isolated and left Singleton following several arrests for intoxication, an affliction which was all too common for war veterans. In 1929, Francis passed away from trench tuberculosis in the segregated Aboriginal ward of the Macleay District Hospital at Kempsey, having never reunited with his sons. He was buried the day of his death in an unmarked grave.

During the First World War, more than 1,000 Indigenous Australians such as William Francis served Australia. In their eyes, they fulfilled the most demanding obligations of citizenship, fighting and dying alongside their countrymen on the shores of Gallipoli, and amidst the cruel mechanised slaughter of the Western Front. In doing so they established a strong tradition of Indigenous Australian service, a tradition that continues to this day.

Upon their return to Australia, these veterans found their status in society had continued to decline. Despite their service to “King and Country”, which came at great personal cost to some, they were not treated as citizens nor were they given rights equal to those of white Australians, let alone returning war heroes.

Regardless, the resilience and resistance shown by Indigenous men and women like William Francis contributed to changing attitudes and culture. Their honour and sacrifices in war and in peace left a legacy for future generations of Australians.

Kylie Blundell

Great great granddaughter of William Francis