Serving under the Protector

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people.

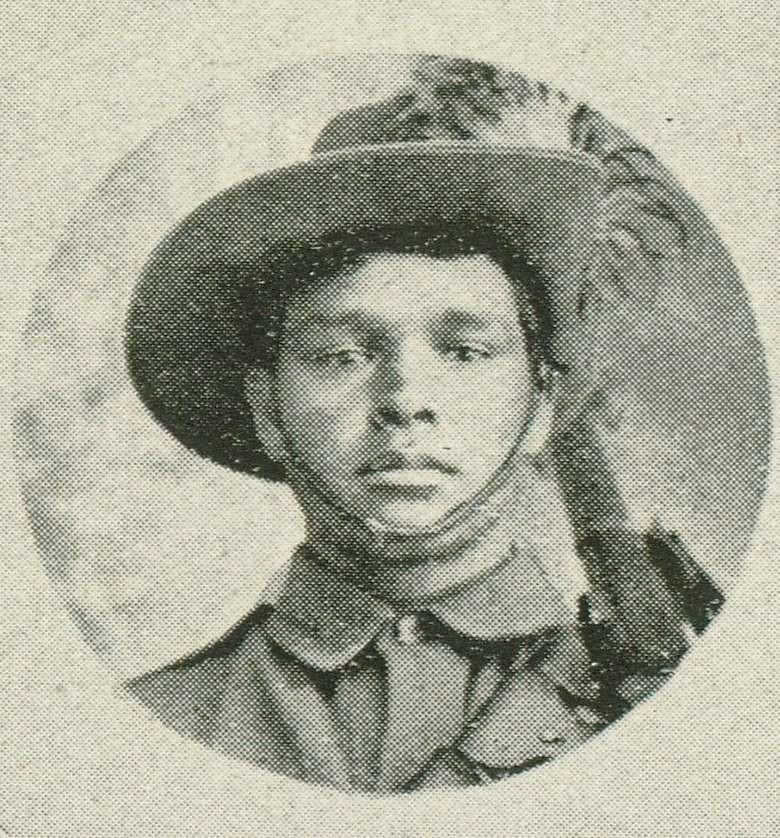

Jack Harry Norman was one of the soldiers pictured in The Queenslander Pictorial supplement to The Queenslander, 1918. Image: Courtesy State Library of Queensland

Jack Harry Norman was just 18 years old when he volunteered to serve during the First World War.

He had to seek permission from a parent or legal guardian because he was under the age of 21.

But with no living relatives, “the whereabouts of [his] parents not known”, Jack was forced to name the Chief Protector of Aboriginals in Queensland as his next of kin.

The Chief Protector would also sign Jack’s permission form, writing to the recruiting officer in Bundaberg to say: “I hearwith give formal consent on behalf of the parents of the half-caste Jack Harry Norman to enlist in the Australian Imperial Forces.”

Jack would go on to serve as a sapper with the 1st Field Squadron Engineers in the Middle East. He was one of more than 800 Indigenous Australians who experienced active service overseas. The Australian War Memorial has recorded more than 1,100 enlistments or attempts to enlist to serve in the Australian Imperial Force, despite restrictions preventing them from doing so.

For Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial, Jack’s story is a powerful reminder of the added restrictions Aboriginal people faced as they fought to serve their country.

“Jack’s story is reflected in numerous records across our research, where younger Aboriginal men try to enlist during the First World War,” he said.

“He was moved to Barambah, which is now Cherbourg Aboriginal Mission, as a child. And the Protector actually signs his permission slip to enlist in place of his parents.

“It reflects the imposition of separate laws in relation to the segregation and management of Aboriginal people that were in place across Australia in the various states.

“Under the various legislations that were put in place, the Protector became the custodian of all Aboriginal people in the state. He then managed all of their affairs: where we lived; how we moved freely; our ability to earn an equal wage; and even our ability to marry.

“All of these considerations, which we would now consider our human rights, were taken away from us and managed by the Protector of Aboriginals in each of the states.

“This is reflected in the stories of these young Aboriginal men having to seek permission to enlist. Where you would normally seek consent from a parent, the Protector acted as the legal representative for some of these younger men.

The camp of the D Field Troop Engineers, Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train at the wine cellars at Deiran, Palestine. A pumping house is on the right.

“Jack still wanted to enlist, but to do so he had to get the Protector’s permission.

“It’s reflective of the nature of living under the Protector for so long, that a young man sees the Protector as his parent and he has to act in that role.

“By the laws of the day, all Aboriginal people born after a certain date, depending on which state you were in, fell under the custody of a Protector of Aboriginals: basically a white minister who was entrusted with the ‘protection’ of Aboriginal people.

“The impact of these policies needs to be spoken about. But what shines through is the willingness of our men and women to still enlist... their dedication to serve and defend country, and the additional steps that our men and women had to take just to go and fight for the country.

“In some case their medals were actually sent back to the Protector. If they made the ultimate sacrifice and they had no living relatives, the Protector was in receipt of the memorial plaque and scrolls as well as the medals for those soldiers."

John Henry Norman was born in Croydon, Queensland, on 24 October 1899. Little is known about his family because he was taken to Barambah mission as a child and sent out to work at the age of 13 to provide labour services to the rural industry.

“He was working on a cane farm and the money he was earning would have been sent back to the Protector,” Michael said.

“The Protector in the various states would enter into agreement with the farmers. They were technically to pay two pounds six shillings for a week’s work of Aboriginal labour, but the Protector would tell everybody that they were holding the two pounds in trust for the Aboriginal person, and so we were given the six pence.

“So imagine, you’re working 14-hours-a day, seven-days-a-week, for six pence, which is about 40 cents in today’s money.”

Jack had been working on a cane farm near Bundaberg when he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in August 1918.

“We don’t know directly why he enlisted, but we’re thinking that the equal pay that he was entitled to would have been a factor,” Michael said.

“As with his non-Indigenous brothers and sisters, he wanted to do his civic duty. He wanted to be loyal to his country. He wanted to defend Country. But the chance to be paid equally was also a strong attractant to our young men and women. It was the chance get out of the yoke of the Protector for a little while, to go out and be seen, and to hopefully be treated equally, and to have the same opportunities as others to advance in the military.”

Rishon, Palestine, November 1918: Officers and men of D Field Troop and Bridging Train. Note the horse drawn pontoon wagons.

Jack left Brisbane on board the troopship HMAT Malta and arrived in Egypt 10 days after the armistice was declared.

But there was no thought of returning home. After training at the Moascar depot, Jack was assigned to D Field Troop and Bridging Train, Australian Engineers.

He was among 15 reinforcements who joined the troop on Christmas Day 1918 at Richon, Syria. They were issued with Christmas comforts, shown their tent accommodation and made to feel “at home”.

As units were reorganised and disbanded after the war, Jack was absorbed into the 1st Field Squadron Engineers, maintaining services and infrastructure for the remaining troops.

Jack returned on the same ship he had arrived on, HMAT Malta, and disembarked in Australia in October 1919, almost a year to the day after he had left.

“He was granted an exemption from the Protection Act when he returned, and that allowed him to travel to NSW,” Michael said.

“It was what was referred to as a ‘Dog licence’, and so he didn’t have to live under the conditions that were imposed upon him as a younger man.

“But in doing that, we found he settled at New Angledool, which is another mission, on the NSW side of the border.

“We know that because he was living there when he applied to receive his war medals in 1936 and his application was supported by the mission manager at New Angledool mission.

“As an exempt man, he would have had to seek permission to go and live at another mission. So he’s had to get an exemption from the Queensland Protector to travel to NSW, and then he’s had to rescind that permission to be able to live as an exempt man so he could live on the community at New Angledool, where he spent of the rest of his life.”

Jack died at Brewarrina in 1972 at the age of 78.

Today, his name is listed on the Memorial’s Indigenous Service list.

“Jack’s story reflects the attitudes of the time and the circumstances that Aboriginal people were living in across the country. But it also speaks to the willingness of our young men and women to volunteer, and the extra steps they were taking to enlist, and that’s why these stories are important,” Michael said.

“The stories like this that we find reflect the implications of the restrictions that were in place – but also the willingness of our men to go and fight for a country where they weren’t entitled to the rights that they were fighting for.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial. A Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is trying to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of any person of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who has served, or is currently serving, or has any military experience and/or contributed to the war effort. Michael would like to get further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au