Jack Millett: the mapmaker of Colditz

Lieutenant Jack Millett was an incorrigible escape artist. Having served in the Western Desert, the young Australian army officer was captured by German forces during the fighting on Crete in May 1941.

He was determined to escape, and planned his first attempt during the three weeks he was imprisoned at Salonika. He and a fellow prisoner hatched a plan to escape over the wire, but quickly changed their minds when five Cypriots rushed the wire and were mercilessly shot down.

Jack Millett at the Rottnest Training Camp in Western Australia.

Jack was moved through Austria to Leipzig, Germany, and then to Oflag X-C at Lubeck where conditions were poor and food was scarce. He devised a plan to faint during parade in order to be admitted to the camp hospital, where food rations were better.

Soon after, Allied aircraft bombed the town and dropped incendiaries on Lubeck’s flak defences. Some fell on the prisoner of war camp, destroying the German officers’ mess; one landed just outside Jack’s window, another in the room next door.

Jack, who had worked for General Motors and as a panel beater and miner in Western Australia before the war, was eventually transferred to Oflag VI-B in Walburg, north-west Germany, where he was caught digging a tunnel out of his own hut with another prisoner.

Lieutenant Jack Millett with his father-in-law Ernest Cary and his son Bob.

He was then dispatched to Oflag VII-B, in Eichstatt, Bavaria, where he again tried to escape. The plan was to dig a tunnel north from one of the camp latrines, under the rocky slope, out of the camp, and up to a villager's chicken coop about 30 metres away. The soil from the tunnel was spread underneath huts in the south-eastern end of the compound so that the guards wouldn’t suspect.

In June 1943, Jack was one of 65 men who escaped through the tunnel in one of the largest mass escapes of the Second World War. After five days on the run he was recaptured by two armed members of the Hitler Youth and their Alsatian dogs. All 65 men were recaptured, but not before their escape efforts had tied up more than 50,000 German police, soldiers, home guard and Hitler Youth for a week.

After 14 days' detention on meagre rations in the dungeon-like rooms of nearby Willibaldsburg castle, the escapees were sent to the infamous Oflag IV-C, a forbidding Renaissance-era castle in Saxony better known as Colditz.

Colditz Castle overlooking the river Mulde.

Situated on the side of a cliff and surrounded by a dry moat in the heart of Hitler’s Reich, Colditz was considered escape proof. Its outer walls were two metres thick, and it sat on a sheer cliff 75 metres above the River Mulde.

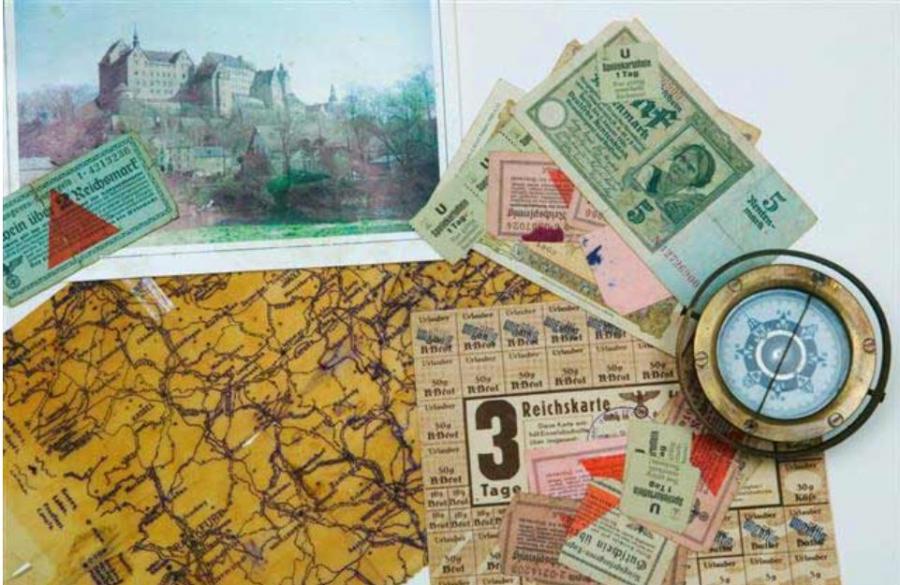

Jack would not escape again, but he did his best to help others. Having studied technical drawing at school, he proved to be a talented map maker, producing high-quality escape maps that were essential for Allied prisoners to escape occupied Europe.

Jack’s remarkable story is told at the Australian War Memorial as part of Against all odds, a special temporary exhibition featuring stories of escape and endurance from the First World War to Afghanistan.

Prisoners of war turn to wave towards Colditz Castle as they are marched across the Adolf Hitler bridge.

Curator Dianne Rutherford has long had a special interest in Jack’s story.

“Colditz was the camp for the incorrigibles — those who had continually attempted escape — and for the 'prominente' — people with prominent connections who could be used as hostages,” she said. “They were the bad boys – the incorrigibles – the ones who kept trying to escape, and they were sent to Colditz because it was meant to be escape proof.”

However, putting the most determine escapees together meant they could plot further escapes. The prisoners were soon digging tunnels, slithering through sewers beneath the castle, climbing down the walls with knotted bedsheets, and tailoring German uniforms so they could stroll out the gates.

One enterprising prisoner dressed as a woman to fool the guards, while another was packed into a Red Cross Tea chest, and another was sewn into a mattress.

Later “ghosts”, officers who had faked a successful escape and hidden in the castle, would take the place of escaping prisoners at roll call in order to delay discovery for as long as possible.

Prisoners of war being marched out of the gate of the Colditz Castle.

In one of the most daring plans, however, prisoners built a marvellous glider in the castle’s attic using books on aircraft design that they found in the prison library. The war ended before they could fly it, but such persistent escape attempts – some of which were successful – meant the number of German guards eventually outnumbered the prisoners.

“Jack was part of the escape committee and was one of the few Australians who were imprisoned in Colditz,” Dianne said. “But he never attempted to escape after that; he was considered too important to be allowed to escape because he became the map maker of Colditz.”

Although they are too fragile to be on display, a dozen of his maps – two master maps and ten copies – are part of the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial.

“He was quite a collector and he had a fantastic collection of items from his time during the war,” Dianne said. “He kept a duplicate key that he made to get into one of the supply rooms in Colditz, and he also kept his master maps, as well as some of the reproductions.

“The two masters are so rare that I don’t know if any others actually exist to be honest, and the mimeograph copies are pretty rare as well.

“They were made using jelly from the Red Cross food parcels.

“There were two sources of jelly – your fruit jelly, like Aeroplane Jelly, which they would sometimes try to sieve to get the sugar and the colour out, and then there was the jelly from your tinned meats.

“They would melt it down and create a flat surface in a container, which they could then use to create a copy of the master.

“The master maps were hand-copied from maps that the prisoners often stole or bribed guards for. They were copied on to a waterproof kind of paper, a bit like baking paper, which they could draw on in indelible ink.

“They could then put the master down on the set jelly, and when they pulled it off, the ink would be transferred onto the jelly.

“They could then put blank pieces of paper down on to the jelly to create a perfect reproduction which they could then draw over again in different colours to show roads, railway lines, borders, and that kind of thing.

“It was a quicker way of doing it than copying out every map out by hand, and a lot of the men who did it had learnt the technique at school where they used it to do programs or school newsletters.”

Each map took hours to produce, but Jack didn’t mind. He was optimistic about the end of the war and would often tell his fellow prisoners that Hitler could never win. Although convinced it was a matter of time before they were all free, he was prepared to do everything he could to help those who wanted to escape.

When US forces reached the town of Colditz in April 1945, the Germans established and reinforced defences in anticipation of an attack. The Americans sent out reconnaissance planes and began ranging shells on the town as preparation for a bombardment.

On 13 April, prominente prisoners were taken from Colditz and moved towards Austria. When the German kommandant was ordered to move the remaining prisoners into the woods the following day, the senior British officer, Lieutenant Colonel William Tod, refused.

“That afternoon, the shelling of the town began, and the prisoners cheered as they watched events unfold from the castle windows,” Dianne said. “The prisoners laid out a huge homemade Union Jack in the courtyard and spelt out ‘POW’ with sheets, in the hope that the American reconnaissance aircraft would spot them, but unfortunately the Americans did not see the makeshift signs and flags at first, and on 15 April their artillery ranged on the castle, letting off some small rounds.”

This key was made by Millett in order for the prisoners to secretly access the food store at Colditz.

It was a sight Jack would never forget.

“For our own safety we were told to go down into the cellars, but I stayed at an upstairs window,” he later recalled. “I certainly didn’t want to miss all the fun, and I saw all that went on. I’ve read where Douglas Bader was knocked off his tin legs by an airburst, but this is not so — he wasn’t in his room at all. He was down in the courtyard gleefully calling, ‘Where is the Luftwaffe? Where is the Luftwaffe?’ to the cowering guards. But there was certainly some hot metal flying around, and I’ve still got a piece of shrapnel that came flying in through the window.”

Jack kept the piece of shrapnel for the rest of his life, and it is now part of the National Collection.

The piece of shrapnel collected by Lieutenant Jack Millett during the Battle for Colditz.

The Americans had fired a few ranging shells – not realising that Colditz was a prisoner of war camp – and were seconds from opening fire when a driver spotted a French flag hanging out of a window.

“Hey, Lieutenant, hold it!” the driver yelled. “They’ve stuck some flags out… I’m sure some of our boys are in there.”

The artillery officer in charge of the attack later told the prisoners that ten seconds had separated them from annihilation.

After the Americans advanced on the castle and liberated the prisoners, Jack Millett was flown to England and returned to his family in Australia in August 1945.

After more than five years of war, the mapmaker of Colditz was finally home.

Read Curator Dianne Rutherford’s blog about how to make your own escape map here.