'We just had a job to do, and we did it'

When Jim Burrowes went to war in January 1942, he came from a family of seven. By the time he returned, his family of seven had been reduced to three.

“It was very hard on poor old Mum,” Jim said.

“[She was] a true heroine. She had got through the Depression following World War I, struggled to bring up the family, and then all this happened …

“My oldest brother was captured at Rabaul in 1942 and my twin brother was shot down on his first mission over Rabaul in 1943.

“When I got home I found out ... my brothers had both been killed …

“My father had died [of a heart attack] during the war in 1942 … and after I got home … my sister died in childbirth … I missed seeing her one final time by a few hours.”

Jim, now 95, served as a Coastwatcher with the Allied Intelligence Bureau’s M Special Unit during the Second World War.

The Coastwatchers were Allied military intelligence operatives stationed on remote Pacific islands to observe enemy movement and rescue stranded Allied personnel. The intelligence they gathered is often credited with turning the tide of the war in the Pacific, their radioed reports giving the Allies a decisive advantage in some of the most crucial battles, including the Battle of the Coral Sea, and acting as an early warning network.

“A lot of people say we were heroes, but I don’t believe that,” Jim said. “We just had a job to do and we did it … and fortunately most of us came home.”

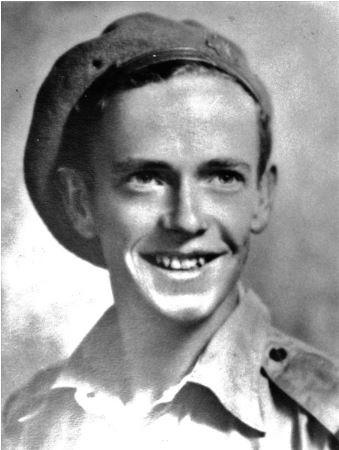

Jim Burrowes in 1942. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Jim was determined to join up.

He and his twin brother Tom were born in Melbourne in 1923 and grew up during the Depression.

His father Archibald had volunteered during the First World War, as had his uncles.

“My father was knocked back [for active service] because he failed a medical test,” Jim said. “He had a suspect heart problem… but I had two uncles who fought in the war: one who came home, and one who was killed.”

His Uncle Les enlisted in October 1914 and served with the 10th Light Horse Regiment on Gallipoli and in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. A sergeant by the end of the war, he was wounded on three separate occasions and never fully recovered, suffering from “shell shock” for the rest of his life.

Jim's uncle Thomas Farrell c.1914. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

His mother’s brother, Thomas Farrell, served in the 16th Battalion and was killed in action at Pope’s Hill on Gallipoli in May 1915. The family never knew exactly when or how he died, and when the Second World War broke out a few decades later, Jim and his siblings were determined to do their bit.

“When the war started in 1939 I was only 16, so I had to wait until I was 18 before I could join the AIF,” Jim said.

“My brother Bob was in the army … and my twin brother Tom was already in the air force because he was an air force cadet … [but] my Mum and Dad wouldn’t sign my papers because the two boys were already in, so I had to wait until I was 18, and when I turned 18, I promptly joined the AIF.”

Jim’s oldest brother Robert tried to stop him. In his last letter home, he asked his mother to “get Jim out if you possibly can,” but it was too late. Jim had already enlisted. He had joined the army just a week before Robert was captured.

The letter was delivered in a bag of mail that was air-dropped over Darwin by the Japanese. Not knowing his brother was dead, Jim later replied. “All well here and thinking of you constantly and praying for the day when it will all be over.”

Jim's older brother Robert Burrowes. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

Jim's twin brother Tom Burrowes. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

To Jim, Robert and his twin brother Tom were the heroes and he was determined to join them.

“My two brothers had already gone up north, and I wanted to be in it,” Jim said. “It was a case of doing my duty … and it was a touch of adventure at that age. I was only 18 and when I fronted up at the army barracks to join, they asked, ‘Who’s worked in an office and who’s a school teacher? Stand over there, the rest of you are infantry.’”

Having worked in a chartered accountant’s office, Jim put up his hand, and his destiny as a Coastwatcher was set. He soon became a signaller and later volunteered for a secret mission with the Americans and the US 7th Fleet Amphibious Landing Force.

“There’s an old adage, when you are in the army, you don’t volunteer for anything, but I couldn’t put my hand up quick enough to get up and into it,” he said.

“Up in the islands, we would land and go in in PT boats and go into enemy occupied territory to see what the situation was like … and pass back the information … When they folded for some unknown reason – we never knew why – I transferred immediately to the Australian Coastwatchers…”

Jim before he headed north in 1942. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

The Coastwatchers were code-named "Ferdinand" after the popular children's book character Ferdinand the bull, who sat among the flowers and refused to fight. It was chosen as a reminder to the Coastwatchers that their job was not to fight and draw attention to themselves, but to sit quietly and spy on the Japanese and gather information.

“We were all under the strict mandate of the Coastwatchers to not confront the enemy, but to hide from [them and], observe and report enemy movements,” Jim said.

“[Our] job … was basically communication [and] not to get caught. [We] were to dodge the Japanese and to spy on them generally, and signal any movements… For example, we’d be able to signal, ‘60 Japanese Betty Bombers on the way to attack Guadalcanal, expect them to attack in two hours,’ so that when the Japs arrived, the Americans were [ready], their planes were up in the air, their ships were at general quarters, and their land army was ready with their anti-aircraft weaponry to attack and repulse the Japanese.

“Admiral Halsey, the general commander of the whole south-west Pacific area stated that the Coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the Pacific War, and later on, General Macarthur also stated something similar.”

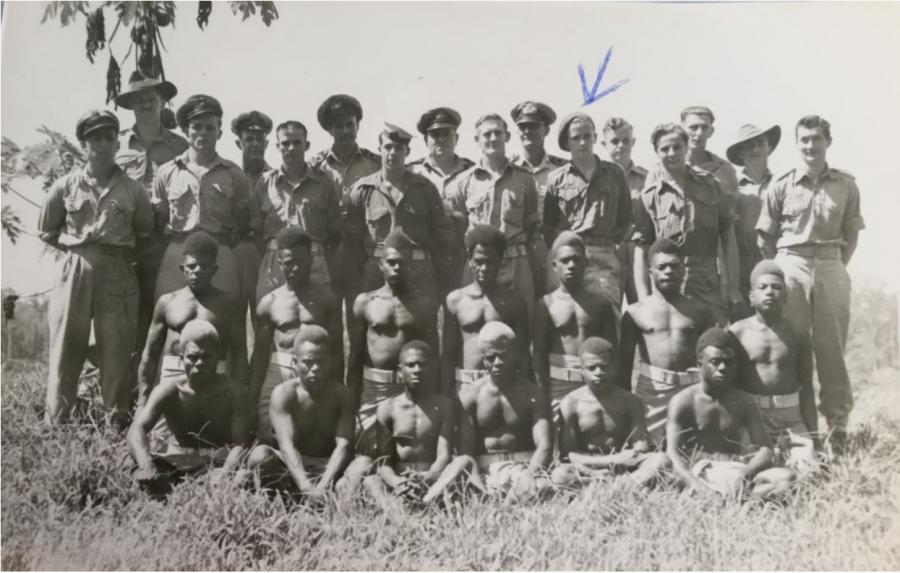

A group of Coastwatchers during the Second World War. The arrow is pointing at Jim. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

It was an Australian Coastwatcher who saved the future American President, Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, after his boat PT-109 was “carved in two” by a Japanese destroyer on the night of 1 August 1943. After the sinking, the crew reached Kolombangara Island where they were found by Coastwatcher Sub-Lieutenant Reginald Evans who organised their rescue.

“They were pretty much gone,” Jim said. “They had no food and they couldn’t even crack open a coconut ... and after the war he invited the Coastwatchers to have a cup of tea at the White House … And, for me, that in a nutshell tells the example of the whole Coastwatchers.”

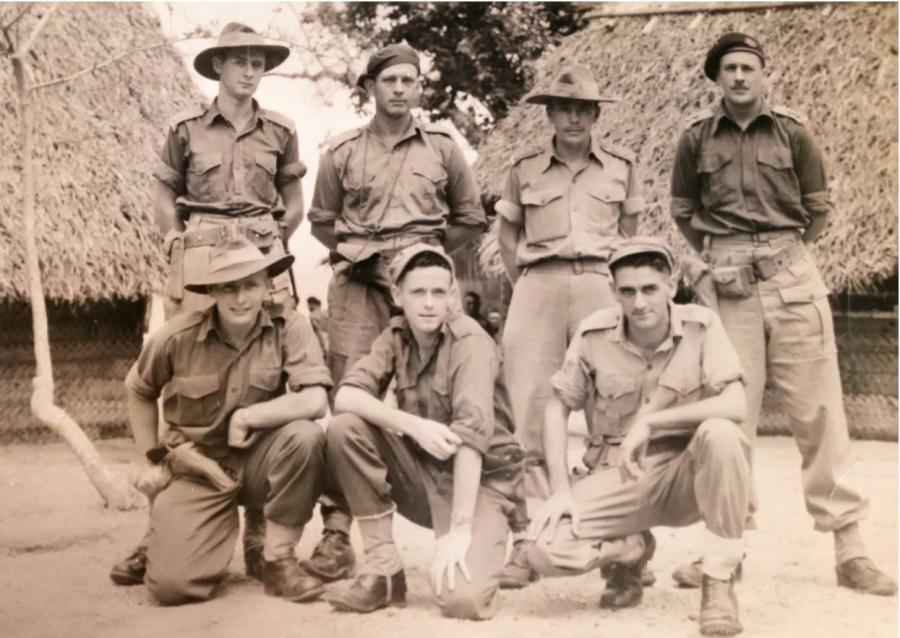

At Tol: Back row, from left: Lieutenant Jack Ranken MM, Captain Malcolm English, Lieutenant ‘Mac’ Hamilton, and Sergeant Rob McKay. Front row, from left: Sgt. Keith King, Sergeant Jim Burrowes (Signaller), and Sergeant Les ‘Tas’ Baillie (Signaller). Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

Jim’s own role as a Coastwatcher included 10 months in Japanese-held territory over-looking Rabaul, where his two brothers had met their fate.

“I went up in a barge in the middle of the night,” he said. “We trekked two or three days up to the Baining Mountains overlooking Rabaul where I joined the captain and a lieutenant and relieved the radio man, who was sick or no longer capable, and the three of us became the only white soldiers to see Rabaul under Japanese occupation.”

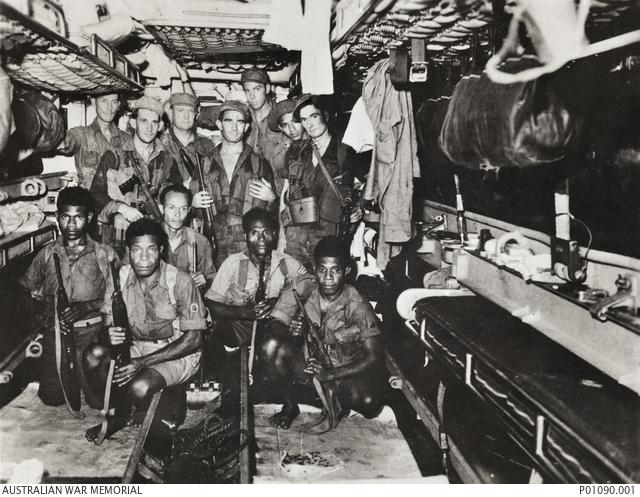

It was a dangerous business, and the men knew they risked being tortured and killed if they were discovered. In March 1944, Jim narrowly escaped death when he was selected as the signaller for the ill-fated Hollandia mission and was replaced at the last minute by Signaller Jack Bunning. When the 11 Coastwatchers paddled ashore from a submarine off Holliandia in West Papua, their rubber crafts were wrecked by the surf and they lost most of their equipment, before being ambushed by the Japanese. Five Coastwatchers were killed, including Bunning. Those who survived somehow managed to escape and, after enduring incredible hardship, rejoined Allied forces.

The Coastwatcher party on board the American submarine, Dace, in 1944. The Coastwatchers were about to land at Hollandia.

“They don’t leave you, those memories,” Jim said.

“And to this day, I still know my Morse Code backwards…”

He feared the worst when the radio failed one day in New Britain.

“I was on a schedule and the damn radio wouldn’t work and I thought, ‘What on earth?’” he said.

“The sun was shining, and I … pulled it out of its frame, and turned it upside down and looked at all these things, and do you know … we had spent six weeks learning Morse Code, but not a word … about how to fix the bloody things.

“So there I was, and you wouldn’t believe it, I had a brown paper lunch bag with some spare parts, so I looked at these orange and red condensers and resistors, and I sorted them out across what seemed to be a similar pattern, and all of a sudden I got a signal.

“From that day to this, I can’t remember how: I certainly didn’t have a soldering iron, and I didn’t have any pliers or anything else, so I don’t know how I got it going.”

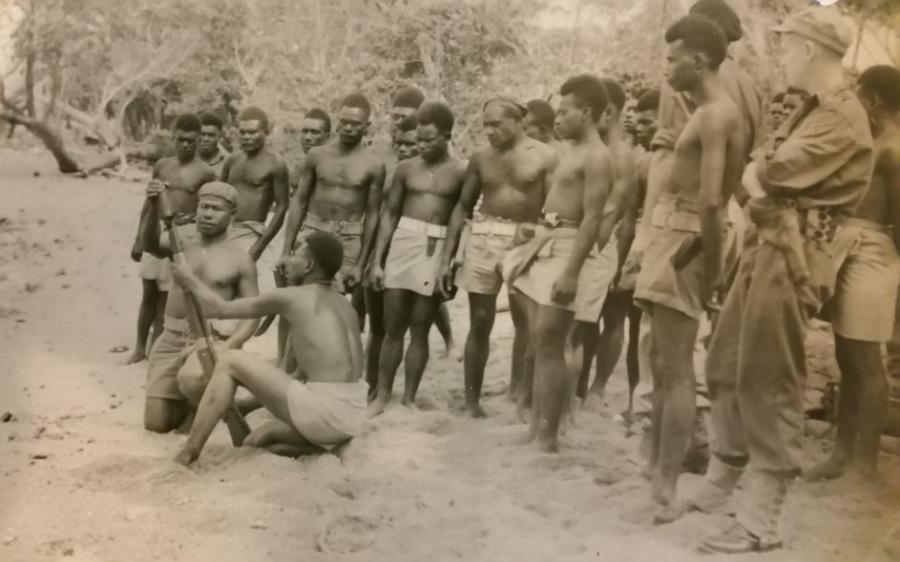

Jim, right, supervising Papuan troops using a mortar gun on New Britain. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

He is particularly grateful to the Papuan troops who helped them during the war.

“What we would have done without the natives, I don’t know,” he said.

“The three basic components of a Coastwatchers’ party were the expatriate leader, the radio operator and the natives, and without any one of those three, there wouldn’t have been the Coastwatchers.”

Jim soon learnt Pidgin English and can still recite the Lord’s Prayer. “It’s a very descriptive language… and I still remember that,” he said.

He credits the Papuan troops with keeping them safe, and remained in contact with them after the war.

“What a wonderful part they played,” Jim said.

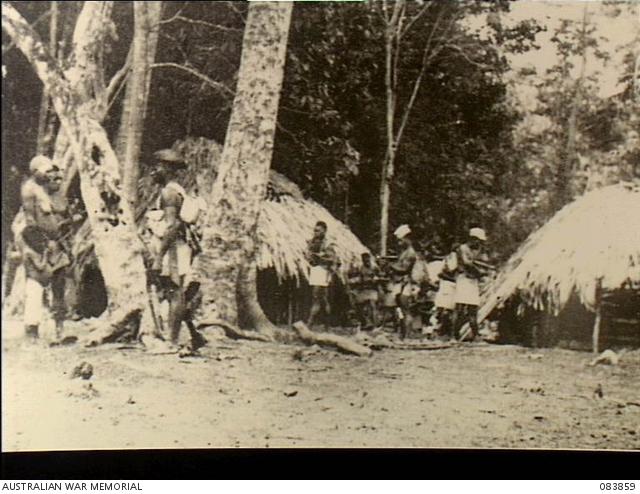

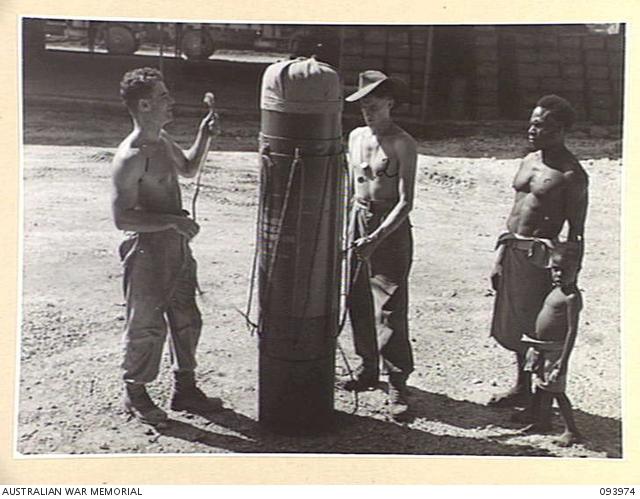

“They carried our radio equipment and all of our other gear, climbed coconut trees to erect the radio aerial, built our thatched accommodation, and retrieved our food and other supplies which were dropped in parachuted ‘storepedos’ by Liberator or Catalina…

“We’d camp on a ridge so the Japs couldn’t jump us and we’d have two or three natives at each end of the ridge to warn us of any danger ...”

A typical Coastwatcher camp.

The conditions they endured, day in and day out, were difficult at best.

“But I was never frightened… Once we heard a shot during the middle of the night and got a bit of a scare but … I never saw a Jap. If I had, I probably wouldn’t be here today.

“There were only about 400 Coastwatchers, and unfortunately 38 got caught, and were tortured and killed, and what have you, but I was lucky: I made it home to get married and to have four kids and have a happy life.”

He will never forget the day the war ended and it was finally over.

“I was still up in the Baining Mountains and we got a message that the war was over,” he said. “I sent a message down to headquarters [asking if we] could we walk into Rabaul…

“You know how it is in fantasy land. I somehow thought that I could question any natives who were escaping out of Rabaul, and [find] Robert or Tom. We didn’t know about the Montevideo Maru, and I thought Tom might have survived being shot down, so I had the vague hope that one of them might be still alive as a prisoner…

“We could have walked there in about half a day or something, but permission was predictably refused because half the Japs didn’t know the war was over…”

Food and other supplies were dropped in parachuted ‘storepedos’ by Liberator or Catalina.

It wasn’t until after the war that Jim finally learned what had happened to his two brothers.

His oldest brother Robert, a sergeant with the 34th Fortress Engineers, had been captured by the Japanese during the fall of Rabaul on 23 January 1942 and was on board the unmarked prisoner of war ship Montevideo Maru when it was torpedoed by the submarine USS Sturgeon off Luzon on 1 July 1942. The ship sank within 11 minutes, and all 1,053 Australian prisoners of war were killed, including Jim’s brother Robert, who was just 24 years old. The sinking of the Montevideo Maru and subsequent loss of Australian lives, including 208 civilians, became the largest maritime disaster in Australian history.

Jim’s twin brother Tom had also been killed. A Flight Sergeant in the RAAF, he was a wireless air gunner in 100 Squadron when he was shot down on his first mission over Rabaul on 14 December 1943. His Beaufort bomber was one of five planes that did not return that day and he was reported as missing in action until after the war. He was just 20 and never got to celebrate his 21st birthday.

The twins: Jim, left, with his brother Tom. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

It was devastating news for their mother Alice, who was mourning the loss of her husband, who had died of a heart attack at the age of 54 at home in Middle Park on 25 August 1942. Jim had learnt of his death on his way to Queensland for training.

Jim’s sisters, Pat and Helen, had also helped with the war effort. Pat worked at the Allied Works Council in Melbourne, including as Secretary to the Chief Mechanical Engineer, from 1942 until 1946, and Helen was employed with the United States Army in Australia, working as secretary to Brigadier General Frank Clark who commanded a convoy that brought two brigades of anti-aircraft artillery to Australia in March 1942.

Tragically, Helen died in childbirth on 21 December 1945 and her child was also lost. She was just 30 years old and a railway strike prevented Jim from reaching her before her death.

“I was on my way to see her in hospital in Bendigo after returning from the war,” he said. “She was in childbirth, and I couldn’t get there because the damn train people were on strike.

“Having treasured so many letters from her during my years away … I missed seeing her one final time by a few hours …

“My family of seven had been reduced to three: my mother, my sister Pat, and me.”

Jim, front left, with his siblings, c 1935. Back row: Pat, Robert and Helen. Front row: Jim and his twin brother Tom.

Now, more than 70 years later, he has created a website, The Last Coastwatcher, to honour the men and women who served and ensure their role in the Pacific War is not forgotten.

“There were three of us in my family at Rabaul and I’m the only one who returned,” he said.

“I became a chartered accountant and a licenced company auditor and got on with it and didn’t really talk much about the war [until recently].

“My last mission is to let people know to be proud of the part the Aussies played.”

Since then, his articles have been printed in magazines and newspapers in Australia and England and he has received feedback from as far away as Portugal and Brazil.

“It’s spreading like wild fire all over the world,” he said. “And I’m just so pleased … It’s about the Coastwatchers, not me, and I’m only too happy to spread the word of the feat that the Coastwatchers did.”

Another group of Coastwatchers, including Jim's best mate Les ‘Tas’ Baillie, back row, fifth from left. Jim is in the front row, third from right.

Today, he still has the Morse Code key that he used to send messages during the war and his grandchildren call him ‘Didah’ after the Morse Code for the first letter of the alphabet, A, or Ace, which sounds like ‘di dah’ when spoken.

For Jim, it’s a constant reminder of a time he will never forget.

“I’m a firm believer that life’s a lot of luck,” Jim said.

“Of course, there are two kinds [of luck] – ‘good’ and ‘bad’ – [and] fortunately, I had my fair share of the ‘good’!

“I was lucky to be selected to be a radio operator, instead of infantry.

“I was lucky to be replaced as the radio operator in the disastrous Hollandia infiltration party when the original guy, Jack Bunning, was ambushed by the Japanese and killed.

“I was lucky not to be caught and killed by the Japanese, while hiding in the jungle…

“[And] I was lucky to come home.”

Jim's wife Beryl during the war. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes

Today, he lives in Melbourne with his wife Beryl, who served with the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force during the war. They married in 1951 and have four children and four grandchildren. They named their two sons, Robert and Tom, after Jim’s brothers.

Jim and his wife Beryl on their wedding day. Photo: Courtesy Jim Burrowes