'I didn't think it would be like this'

James Cronk can tell you the exact moment he landed on Tarakan during the Second World War. “That was no picnic,” he said. “They had tank traps, and sea mines on the beach, and a jetty that was loaded with explosives.

“Up on top of another hill there they had an oil tank full of oil and they were going to pump that into the sea and set it alight … We were out there in the boats, but we didn’t learn about that until after the war.”

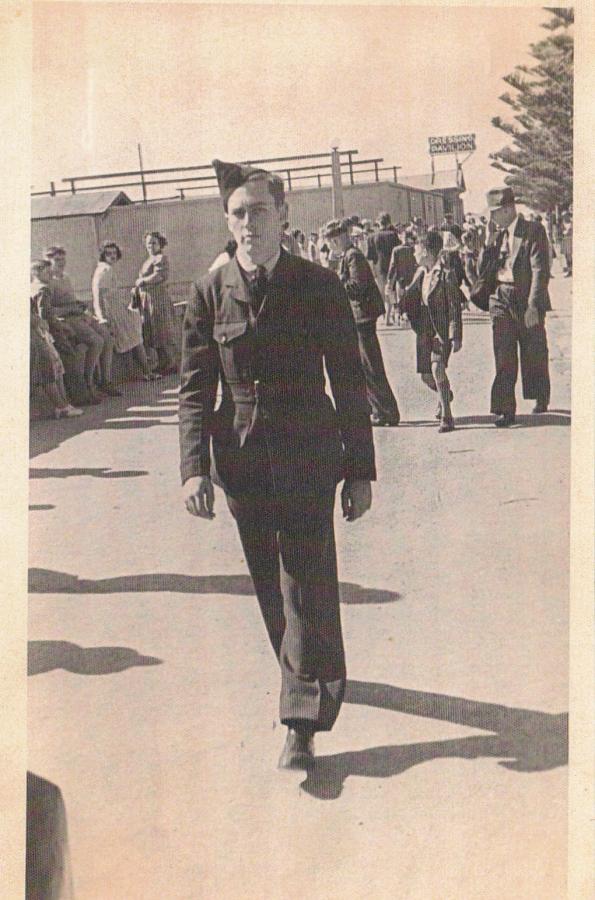

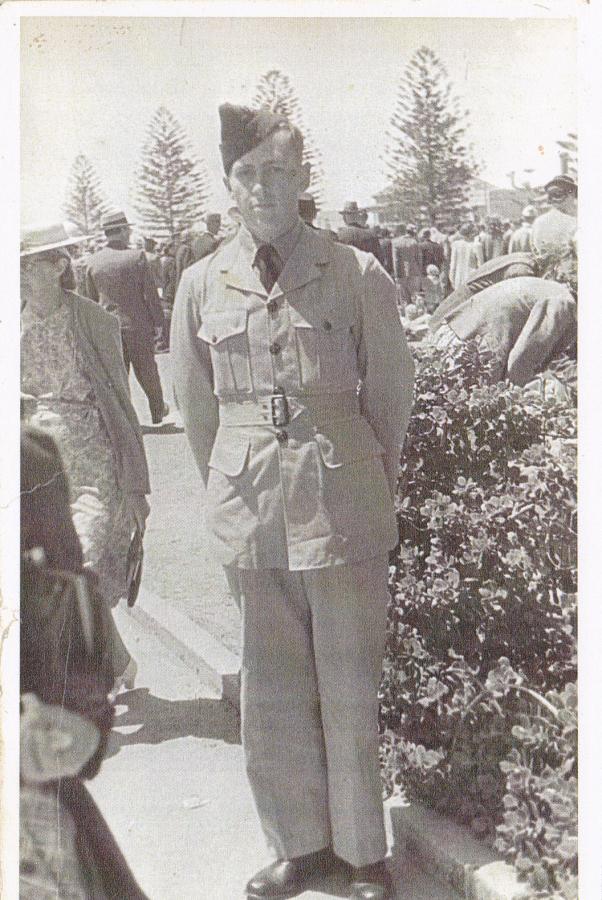

Jim Cronk in his air force uniform.

Photo: Courtesy Jim Cronk

As a young aircraft technician in the Royal Australian Air Force, Jim had waded ashore on 1 May 1945 as part of Operation Oboe One, the first stage of the Borneo campaign.

“I got interviewed there about the invasion and I said, ‘Oh, I didn’t think it would be like this.’

“You could hardly hear yourself talk, and then they cut the pontoons off the side of the boats, and as they hit the water, they would go ‘bomp’, because there was nothing in them.”

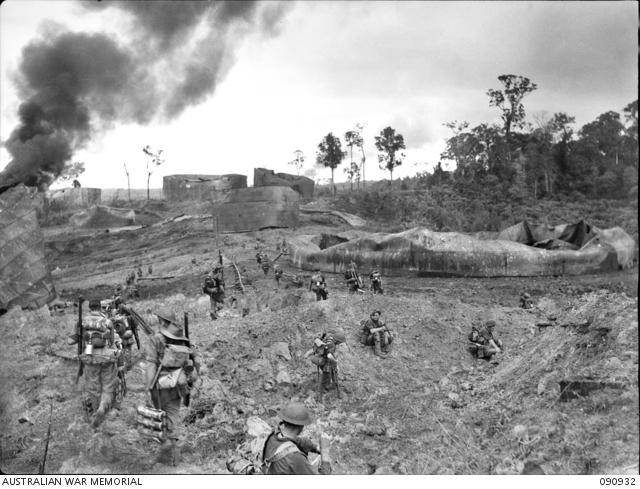

A Landing Ship, Tank (LST) high and dry at low tide on Tarakan on 1 May 1945. Troops and vehicles stand on one of the pontoons used for crossing the mud.

Trucks coming off the Landing Ship, Tanks became bogged in the soft sand during the landing by the 9th Division AIF and RAAF units.

Tarakan had been an important oil-production centre before the war and was significant for it oil infrastructure and its airfield.

The Japanese occupied the island in early 1942 and the capture and repair of its airfield was at the centre of the Oboe One operation.

It began with an amphibious landing by Australian forces in the early hours of the morning. The two lead battalions – the 2/48th and the 2/23rd, with the 2/24th in reserve – were supported by a massive pre-invasion air and naval bombardment, and pontoons were floated onto the beach so that supplies could be unloaded in the soft muddy conditions.

Indonesian, Netherlands East Indies, and Australian soldiers with Allied Equipment on the landing beach.

The Landing Ship, Tanks (LSTs) which landed troops of the 9th Division AIF and units of the RAAF at Tarakan in May 1945.

“‘Diver’ Derrick took his troops in at 7 o’clock, and at 10 o’clock, Jim was there too,” Jim said.

“A chap came on the LST [Landing Ship, Tank] and called out numbers; mine was among them, and he said, ‘Get your rifle and your bayonet, emergency rations, ammunition, leave your ID here, and over the side into the barge.’

“Although I was in the air force, it didn’t make any difference… We went in, and we were unloading supplies … and when it got dark, he said, ‘We’re expecting a breakthrough tonight … you, in-between those two soldiers, you, in-between those two soldiers,’ and so it went along.

“We felt half full of water all night, and I couldn’t’ sleep. I saw a figure down on my left, and I moved my rifle around like that. The army bloke said, ‘What are you on?’ I said, ‘Look down my rifle,’ and he said, ‘Oh, don’t shoot, that’s one of ours.’

“I said, ‘I wasn’t going to shoot because it gives your position away,’ and he said, ‘Fair enough, I’ll get rid of him,’ so he got on his two way and got rid of him.”

He will never forget the relief he felt as dawn broke over the island.

“When it got daylight, we stood up, and whoop, there was a Matilda tank sitting right there,” he said.

“I said to the army bloke, ‘Thank goodness there wasn’t a break because, gee, if there had have been a break, I wouldn’t have been much good to you.’

“He said, ‘Don’t worry about that, you would have been alright,’ and I said, ‘No I wouldn’t have been, I would have had to go back to camp to get a clean set of underclothes or I’d have gone straight through to the ground.’

“He said, ‘you’re alright,’ and with that we broke up, and I went back to the LST, got my gear, and went ashore.”

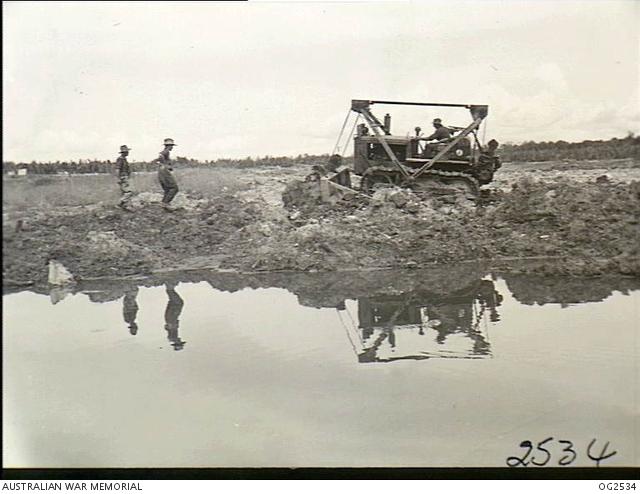

For Jim and his mates, the work had only just begun. The Allies planned to use the airstrip on the island to support the other Oboe operations as part of a general advance towards Java, but it had been severely damaged by pre-invasion bombing.

“It was full of bomb holes and shell holes,” Jim said.

“At that end was the sea, at this end was a big gutter, and behind it was a big hill.

“On top of that hill the Japanese had a tunnel with a 75mm howitzer in it. They would open the doors, push it out, and fire shots down the strip.

“Now, there were machinery and men down there working, and natives as well, filling in these holes.

“There wasn’t a stone on the island – no rock at all – and all we could do was get 44 gallon drums, cut the top out, cut the bottom out, put them in the hole, and fill them up with dirt, spray it with oil – the oil would keep the rain out – and then put steel matting over the top of them.”

While the infantry fought the Japanese in the hills, RAAF engineers were engaged in a desperate attempt to get the airstrip operational.

Jim remembers almost coming to grief on the airstrip as he went about his work with 75 Squadron.

“I was only supposed to be driving weapon carriers, but I was driving anything from trucks to 6x6s and 6x4s and all this sort of thing,” he said.

“I took a Jeep down and I thought, ‘I’ll go for a run down the strip,’ but I got to 40 miles an hour and I nearly turned the Jeep over. They’re pretty hard to turn over, but two wheels on one side came up, so I slowed down after that.”

Working with Kittyhawks in the hot, marshy conditions, was another challenge.

“I used to have to sit out on the end of the wing,” Jim said.

“It was the only way the pilot could see where he was going because the nose was so high, so you would have to walk out there and sit down.

“They’d go down the strip ready to take off, and then you had to guide them back when they came back.

“The pilot couldn’t’ hear what you were talking about, so it was no good talking. It was all hand signals … and you would have to guide the plane – straight ahead, round the corner.

“We were going down the strip, 40 miles an hour, and they got the order to scramble – get off as quick as you can – so we got down to the bottom of the air strip, he hit one brake, swung the plane around like that, and Jim went – vroom – on to the ground, and away he went … the wing went over me.”

It was dangerous work for all those involved.

“One pilot came back and he only had one wing on one side and half a wing on the other,” Jim said.

“The CO was with him, and he was talking on the radio, and he said, ‘Take it in and land it.’

“The pilot said, ‘No the strip’s not strong enough … I’ll take it up to 3000 and jump,’ so he did, but he pulled the string too soon, and the ’chute got caught on the tail of the plane …

“Another plane took off, and when he came in and landed, he had no wheels; somebody had put gun oil in the hydraulics and that glued it all up so he had no wheels to land on and he had a 90 gallon petrol tank underneath full of petrol … but they got him out.”

Jim Cronk in his air force uniform. Photo: Courtesy Jim Cronk

Jim Cronk in his air force uniform. Photo: Courtesy Jim Cronk

It was a long way from where he’d come from.

The eldest of four children, Jim was born in Prospect, South Australia, in 1924. He left school at 14 and was working at an ammunition factory in Adelaide when he enlisted in November 1943.

“I was working at Islington, making 25 pounder shells, on three shifts, and the day that we made the millionth shell everybody in the factory got the sack,” he said.

“The war was still going and we had 30 days to join the army, navy or air force, or be put in the army, so 89 of us joined the air force together.

“I wanted to go in as a medical orderly, but no: absorbent capacity had been reached.”

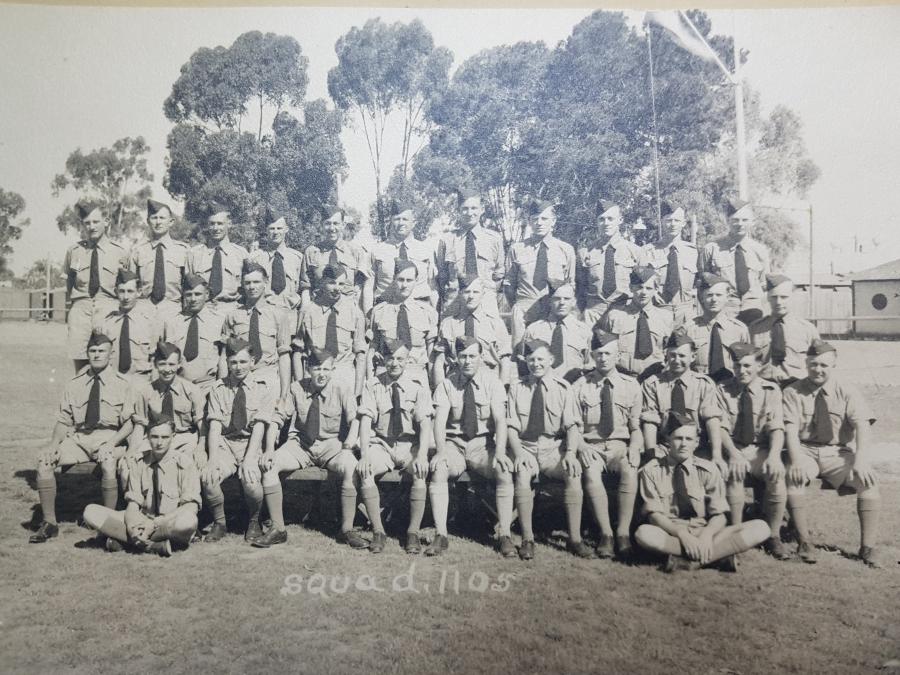

Jim Cronk, sitting on the ground on the right. Photo: Courtesy Jim Cronk

Instead, Jim became a trainee technician and was sent to Shepparton in north-east Victoria for initial training.

“We were at the showgrounds, behind SPC [cannery],” he said. “We did 12 weeks there: drill, drill, drill; how to do as you’re told; discipline; and all that sort of thing.

Back in Adelaide, he learnt how to make models, read a blueprint, and understand “electro-magnetism and all the other things that come into it”.

“When we were at North Terrace and the Exhibition Buildings, we had to go down to the parklands behind the zoo on Saturdays for bivouac training,” he said.

“You’d be standing in a circle and somebody would go walking around behind you and then they’d drop a piece of gelignite behind you, and bang, they’d let a cylinder of gas go, and we had to run through it.

“One day I had my blue uniform underneath my overalls because I was going out for lunch, but the gas got into my clothes and when I went to the pictures that night … the gas filtered out of my clothes and into the theatre.

“All the people who were around where I was sitting were coughing and sneezing, and everything else, but they never said nothing … and I sat and enjoyed the pictures.”

Jim laughs as he tells the story. For him, it was a light moment during the war as he set about learning everything that he could about aircraft.

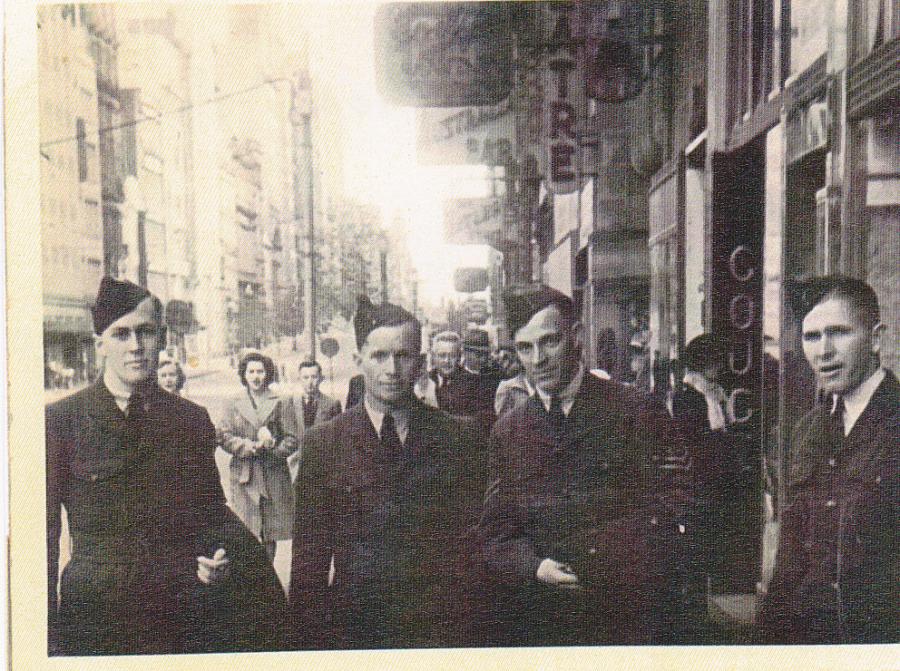

Jim Cronk, left, in Brisbane during the war. Photo: Courtesy Jim Cronk

“I was shifted to the Ascot Vale showgrounds in the middle of winter, and we were sleeping out in the grounds in Masonite huts with wooden floors,” he said.

“We had to learn all about the magnetos, the timing of the engines, and the different sections along internal combustion engines.

“We had a couple of engines there that we pulled to pieces – we had to take the pistons out and the con rods, and all that sort of thing – and then we had to put them together again.

“From there, we had to learn all about the air screws and the different types. We weren’t allowed to call them propellers because … propellers go on boats, not on planes.”

He remembers learning how to start the old Tiger Moths and working on the various aircraft before being posted overseas.

He had married his sweetheart, Audrey Hill, just two months before in October 1944. They had met while he was making shells at the ammunition factory and he would ride his bike around to see her every Sunday.

“I came out of the engine section on New Year’s Day 1945 … and I got posted north on the first day,” he said.

“I was trying to ring my wife to tell her I was posted north and the girl on the switchboard said, ‘Is that an office you’re trying to ring?’ When I said, ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘Don’t you know it’s New Year’s Day and it’s a holiday.’ I said, ‘Well, we’re working, so why shouldn’t they?’”

Jim and his wife, Audrey. They were married on 14 October 1944 at St Cuthbert's Church of England, Prospect. Photo: Courtesy Jim Cronk

The photograph frame that Jim made during the war and kept with him at Tarakan.

After 14 days’ pre-embarkation leave, he boarded a troop train for Sydney and was posted to Townsville, sailing for Moratai with the 2/48 Battalion ahead of the invasion of Tarakan.

The conditions were difficult, but the men made the best of the situation.

“When we were unloading the boats, the tea came in boxes in four gallon kerosene tins … a box of tea went missing and a box of Nestles condensed milk went missing as well,” he said, smiling.

“I was on the truck to take it out to the depot, and I said to the driver, ‘You can pull up here.’ They were on guard duty there, and we shot the boxes of tea and condensed milk out. I said, ‘Take them down to the camp,’ so that I knew where they were, and then we went off, and unloaded the others.

“Nothing was said, and every night we used to have a cup of black tea and condensed milk …

“Then we’d go down to the mess hall and knock off a couple of tins of tropical spread – that was like butter – and we’d get our dixies [mess tins], and, of course, we had ‘choofers’ – the old gas stoves – going as well.

“I had a tin up there with petrol in it, and we made a coil out of copper… and that would heat the coil and of course when it got hot it went, ‘swoosh, swoosh, swoosh,’ all the time.

“That would heat up the water so you could make the tea, but of course, one night the Japanese come over – and you can’t put them things out – so we threw a wet bag over the top of it, and that put it out.”

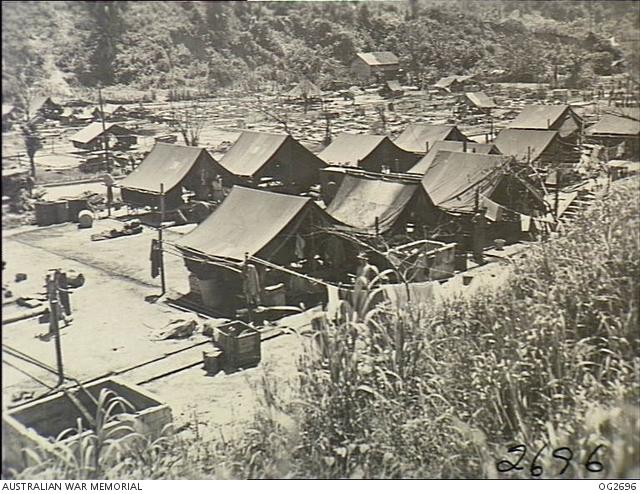

Tent lines in neatly planned RAAF camps which sprang up in the blackened ruins of Tarakan after it was taken.

He laughs as he tells how they made friends with the local monkeys and would find them in their tents.

“We used to tame them on air force porridge,” he said, laughing. “And I’d have one on each side when I was driving around in the Jeep.

“Another day we tried to catch a baboon, but he wasn’t having it; he bit, and one bloke had a nice old fight on his hands …”

He will never forget the last days of the war.

“They dropped the bomb on Hiroshima … on my 21st birthday,” he said.

Considering himself lucky to have survived, he sailed for Sydney in December 1945.

“I was anxious to get home,” he said. “I’d had a chance to go with the occupational force to Japan, but I said, ‘No, I’m married, I’m going home.’”

Jim Cronk at the Australian War Memorial. For Jim, it was important to visit the Memorial and pay his respects to those who were lost during the war.