'You'd find a way ... Aussies always do'

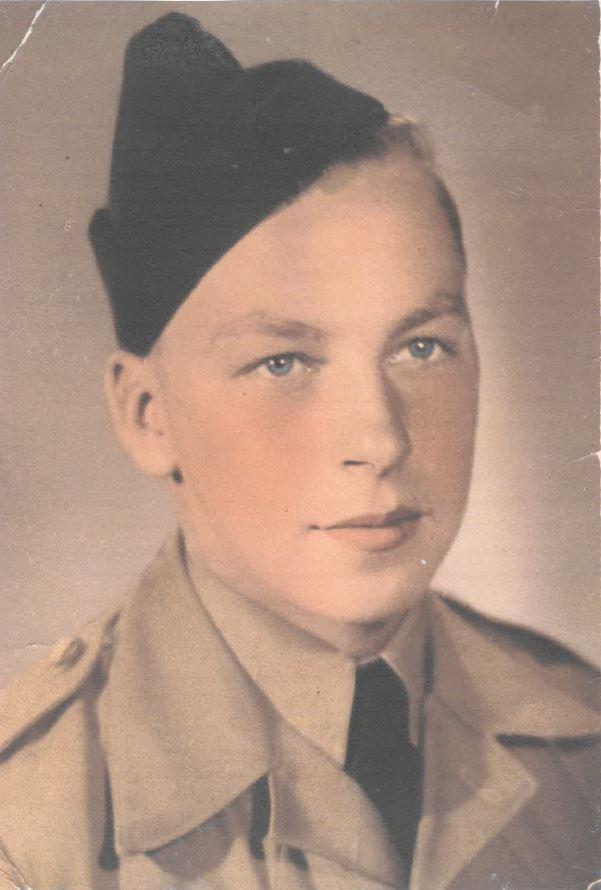

John McKenzie during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy John McKenzie

John McKenzie was used to making do during the Second World War.

So when a pilot asked if he could service an aircraft overnight in New Guinea one evening, he didn’t hesitate.

“You’d find a way,” he said, smiling. “Aussies always do.

“It had to go down to Melbourne for a complete overhaul, and so the officer came in and said, ‘Get a crew together, work all night, and if you can get that aircraft ready to fly to Melbourne in the morning, you can go home,’ so I finished up. I had cooks, clerks, diggers, and I can’t think who else.

“But we did it – we worked through the night – and we got it done.”

The war was over, and the pilot kept his promise.

The C-47 Dakota – VH-CUO (Charlie Uncle Oboe) – flew John and his motley crew of assistants back home to Australia.

John McKenzie, pictured second from right with his mates Vince De Ceire, Bob Bradley, Cecil Lambert and Jack Miller, in front of a Beaufort bomber. Photo: Courtesy John McKenzie

But it wasn’t without a few sacrifices.

“The pilot came and said, ‘Time to go, but you’re only allowed to take so much with you.’

“I’d gathered all of this stuff while I was there – typical Aussie, you know, you pick up things, and haul them away.”

By the time he was due to come home, John had acquired a .45 Colt – “a proper US Army [handgun]”, a .38 calibre pistol, a stone axe, a Japanese sword, and arrows and a bow.

He had also managed to acquire two Purple Hearts, the US Military decorations awarded to those who had been killed or wounded.

“Aussies are scroungers,” he said.

“We used to go raid the Yanks’ Q stores, and when I finished up I had two full presentation Purple Hearts. That’s how good the Yanks were – they had them in the Q stores. I finished up with two of them, and I got some oil cloth, wrapped them up and put them just outside, under the corner of my hut.

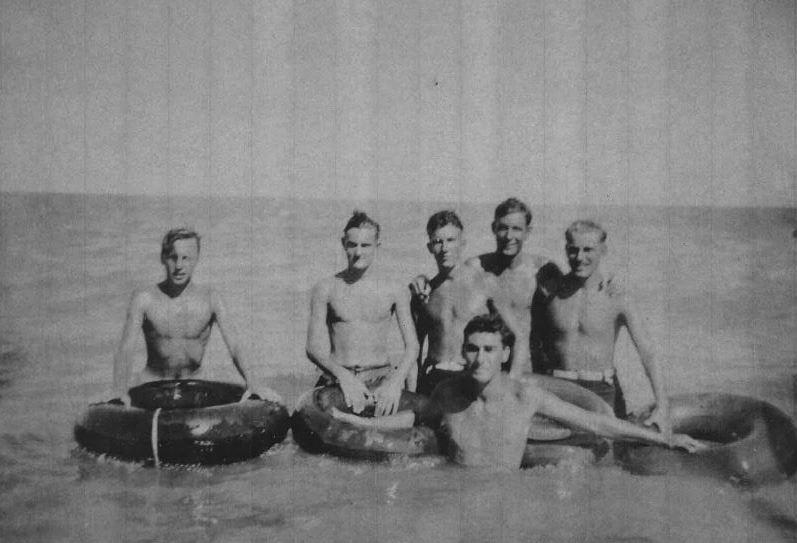

John McKenzie, left, with his mates Bob Bradley, Ron Lake, Jack Miller, Cecil Lambert, and Vince De Ceire, front. Photo: Courtesy John McKenzie

“I farmed out the .45 Colt. The .38 I gave to somebody else. And I just left the arrows and the bow and the axe.

“I brought the sword with me – I tucked it up into the corner of the cockpit among all this other stuff, tobacco and cigarettes and all that – but I forgot all about the Purple Hearts hidden underneath my hut. I often wonder what happened to them. Apparently, they cleared the site afterwards, so they either got buried there, or someone got a lucky find.”

He almost lost his ride when the army tried to requisition the aircraft in Queensland.

“When we got to Cairns, they put a guard on the plane overnight, but then in the morning, we had a bit of drama,” he said.

“The army ‘brass’ turned up with their ‘egg and bacon’ on their peaked caps. They said, ‘Sorry chaps, but we’re going to commandeer this plane, and you’ll have to go down in the train.’

“But the pilot said, ‘No, that’s easy fixed. I’ll just put two letters in my logbook – US, unserviceable – and until that fault is found and repaired, this plane can’t take off. And you won’t be going anywhere.’ They went on the train. We flew.”

John Tasman McKenzie was born in Launceston, Tasmania, on 30 September 1924, the eldest son of Richard and Florence McKenzie, who had emigrated to Australia from Birmingham, England, two years earlier.

“It was a good childhood,” John said. “We didn’t have cars or motorbikes, or anything like that, but you made your own fun, and we thought nothing of it.”

He left school at 14 and was working as an apprentice electrician in Launceston when the war broke out.

“There were just two or three of us younger ones left,” he said.

“All the journeyman electricians had gone because they were older. Then most of the younger ones went, and I wanted to go too, but the boss said, ‘No, no, no, you’ve got to stay.’

“I was in my second year, and I was in charge of the first-year apprentices. That’s just how it was; it was that tight at work. But in the end, I did all sorts of things to annoy the boss – just niggly little things – and he said, ‘All right, John, if you want to go join up, I won’t stand in your way.’ And he didn’t. He gave me a nice reference and off I went.”

John's parents Richard and Florence McKenzie. Photo: Courtesy John McKenzie

John’s father, a stretcher bearer in France and Mesopotamia during the First World War, also enlisted.

“He’d put his age up to go and then put it down to join during the Second World War,” John said.

“It was the thing in those days. You wanted to go with your mates, and all my mates had gone.

“We all felt that you had to go and look after Mother England. But as soon as I decided I wanted to go, the army grabbed me first.

“We went down to Brighton [Army] Camp, which is down south [in Hobart]. The poor blokes were all there waiting, and they came round and [asked] if anyone wanted to join the services – navy or air force – [so I put my hand up, and said], ‘Air force, thank you.’”

John enlisted in 1943 and sailed for Melbourne on board the passenger ship Nairana to begin his basic training at Point Cook.

After training at various camps and bases along the east coast of Australia, John flew to New Guinea in the belly of a huge Sunderland Flying Boat. From Port Moresby, he hitched a ride to Nadzab aboard a Beaufort bomber, sitting on top of sacks of mail and supplies. It was there that he joined the No. 10 Repair and Salvage Unit, a specialised maintenance unit responsible for recovering and repairing damaged aircraft.

The units were formed during the war to help overcome the acute shortage of aircraft amid the high incidence of crashes. Their role was to restore damaged aircraft if possible or to scavenge salvageable parts to use as spares for other aircraft. Because aircraft often crashed at remote and inhospitable locations, the men were often required to work without supporting facilities. They had to use their initiative and employ creative and innovative solutions to scrounge items they needed and talk any locals they met into helping them with locally available resources and manpower. The ability to keep track of which parts were interchangeable between different aircraft was also critical, as was the knowledge of upgrades to various parts.

The repair and salvage units were responsible for recovering and repairing damaged aircraft.

John remembers visiting areas recently vacated by the American air force. He would see aircraft lined up and abandoned, their fuselages deliberately broken to prevent the Japanese from using them, and would have to sift through freshly bulldozed trenches for cans of food and valuable equipment.

He continued his vital work with the unit at the coastal airfield at Lae, before joining No. 33 Squadron, a transport unit, working on Dakota aircraft.

He was lucky to survive when he volunteered to help on a patrol at Mount Lunaman, an important landmark for both the Japanese and the Allies, known as Hospital Hill.

“They’d tunnelled into the hill,” he said. “But when the search party went into there, [they] never came out again. Apparently all the passageways and that were booby trapped, so the order came through to board it up.”

Nadzab, New Guinea, February 1944. Aerial photograph of one of the airstrips at the Allied base.

He was at Lae when the war ended.

“We were in bed, and all of a sudden this hooter started hooting away,” he said.

“[We thought,] ‘God, what’s he on about? Shut up.’

“And then we started to listen. It was Morse. Morse code.

“V.P. V.P.

“God, it’s over!

“And then all of us went a bit mad.

“I went tearing up to the kitchen, and we had a big gong there.

“I was stark naked, and [I went] bang, bang, bang.

“We put this young lad on sentry duty at the beer store with his rifle, and I think he was scared as hell.

“We found out a few days later that it was all a false alarm.

“It was in the afternoon, and I was sitting on top of an aircraft engine, working away, when they came in and said, ‘Yeah, it’s finally over.’

“[I thought], ‘Oh well, keep working.’ We’d already had our celebrations.”

He returned to Tasmania and to his old job after the war.

“I went to Launceston and knocked on the door and Mum came to the door and she said, ‘Oh, I knew you were coming home.’ I hadn’t even mentioned it, but she just knew.”

After being discharged in 1946, John married his sweetheart, Margret Brown. They settled in Beaconsfield, where John, his father Richard, and his younger brother Richard Jr, helped build each other's houses.

He visited the Australian War Memorial on his 98th Birthday and laid a wreath at a Last Post Ceremony in memory of his mates. He was particularly moved to visit the Memorial’s storage facility at Mitchell and see some of the aircraft he had worked on during the war.

“I had a good war, really,” he said simply. “But we were lucky... We came home.”

John McKenzie laying a wreath at a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial. He is pictured with his son Andrew and with Assistant Director Anne Bennie.