'I'll never forget it'

Advisory/warning: the following story contains distressing

content and graphic descriptions.

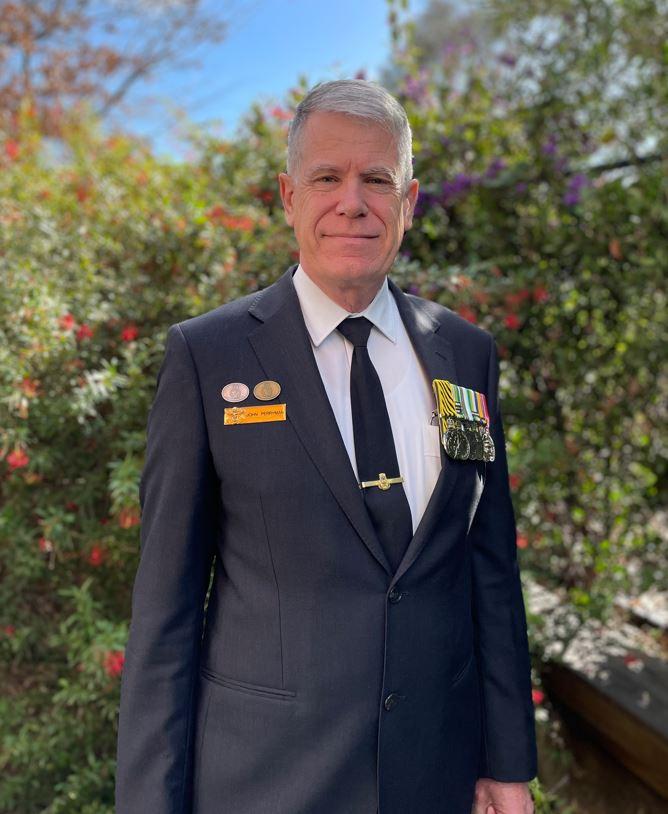

John Perryman served in Somalia in 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

John Perryman doesn’t like to waste food.

“I know what it’s like to see starving people,” he said. “And when you’ve seen starving people you don’t forget that. So I always clean my plate when I eat, and I will not waste food.”

It’s been 30 years since the Royal Australian Navy veteran sailed into Mogadishu harbour aboard HMAS Tobruk in January 1993, but what he saw there will stay with him forever.

Somalia had been mired in conflict since warlords toppled the military dictator, Mohamed Siad Barre, and the country had been brought to its knees, collapsing into clan warfare and civil war. Hundreds of thousands of people died of starvation as the country descended into anarchy, effectively ceasing to function as an organised nation state, gripped by famine.

John Perryman in Mogadishu on 20 January 1993. Perryman donated his uniform as well as his watch to the Memorial. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

The Green Line, Mogadishu, February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

The aftermath of the fighting: the Green Line, Mogadishu, February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

“The destruction in Somalia was complete,” Perryman said.

“Everything had been destroyed and there’d been that much lead and high explosive in the air that even the concrete street lamps and the poles from the old give way signs, they were like Swiss cheese.

“That's how much explosives had been used in Mogadishu. And it was just an absolute mess. You couldn’t turn a light on in Somalia. You couldn’t turn a tap on and have water come out. There was just nothing there. They’d wrecked everything, and yet, there was evidence that at one time, it had been quite the opposite.

“But the longer we were there, the more we learnt that in Somalia it wasn’t where you were from that mattered, but who you were from ... and even then, among the clans and the sub-clans, there was squabbling to pick over the carcass of what was left of Somalia.

Perryman with the commanding officer of HMAS Tobruk, Commander Kevin Taylor, prior to flying into Mogadishu for an ops brief. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Flying into Mogadishu in Tobruk's sea king helicopter Shark 05. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Mogadishu 1993: Perryman, centre, with Josh Tahn and Jim Hill. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

“Mogadishu itself was probably one of the most dangerous places on the planet at that time and we were right in the thick of it.

“It was quite confronting, but I think the most confronting thing for me was the amount of starving children. And not just starving children, but maimed children. Children missing limbs. Faces shot away. And all sorts of terrible injuries.

“I recall one time we joined this army patrol that went through Mogadishu. There were kids waving in the street, and there was one little kid who was waving and smiling, a little girl, probably about eight or nine, and as the vehicle went passed, she turned her head. You could see that part of her face had been shot away. Her cheek was missing and you could see her jaw. It had healed, but it was just open, and I imagine she looked like that until the day she died.”

Perryman on the flagdeck of Tobruk with coalition warships in the background, January 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman.

Tobruk arriving in Darwin for final fuel and water. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Tobruk arriving in Mogadishu on 20 January 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

John Perryman was one of more than 1,500 Australians who deployed to Somalia between 1992 and 1995 as part of Operation Solace, the Australian Defence Force’s contribution to the UN-backed, US-led multinational force, Unified Task Force (UNITAF). Codenamed Operation Restore Hope, UNITAF was charged with securing humanitarian relief operations in Somalia and protecting the distribution of humanitarian aid.

Perryman was the Chief Petty Officer Signals Yeoman on board Tobruk. He had joined the Royal Australian Navy as a 16 year old, inspired by his parents’ service in the British Royal Navy.

“My Mum and Dad were in the navy, and my father was a boy signalman in the Second World War,” he said. “I enjoyed looking at my father’s photo albums and listening to their stories, so I joined as a boy signalman as well essentially, and I loved it.”

Perryman joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1980. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

He’d been in the navy for 13 years when he learnt he was heading to Somalia with Tobruk. The heavy landing ship was to be responsible for transporting 1RAR personnel, vehicles and equipment, and would go on to provide logistic support and respite services to coalition forces. Getting the ship ready for deployment required a massive effort.

“We worked all the way through until quite late on Christmas Eve and then those of us who could, flew home for Christmas ... “We got on a plane again that night and sailed the next day, so it was all very sudden, and very, very quick.

“Some of us had an idea of where Somalia was, but many of the ship’s company, particularly the junior sailors, had never even heard of the place.”

Tobruk on Boxing Day 1992. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Tobruk with cargo at Townsville, December 1992. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

He still remembers seeing his first glimpse of Somalia.

“We arrived late in the afternoon of the 19th of January and ... we came across the horizon,” he said. “By that time it was dark, and there were no lights on the shore, or very few.

“When you come to a continent, you expect to see a loom of light, but Africa was completely the opposite, particularly Somalia... There were some lights around the port area, and to a lesser extent, a little bit further south, at the airport, but that was one of the things I really noticed, it was just this black backdrop of nothingness...

“There were tracer rounds and things like that going off on shore and so news spread around the ship quite quickly that there was small arms fire, and in some cases, heavy calibre weapons being discharged, so we were pretty cautious about going in.

Somalia, 20 January 1993. Note the explosion ashore. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Mogadishu, 21 February 1993: Coalition troops conduct an explosive ordnance disposal operation to destroy munitions discovered at an abandoned bunker site. "The amount of ammunition and explosives that they’d confiscated was unbelievable," John said. "You felt the compression wave from the explosion, and we were anchored probably two miles offshore." Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Mogadishu, February 1993: The smoke from fires lit during rioting at the port. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

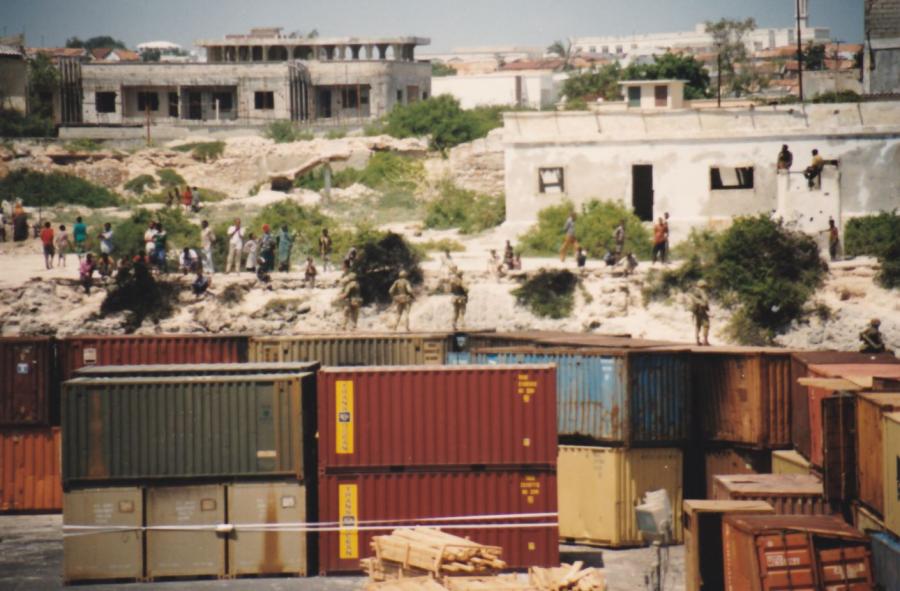

“When the next day dawned we sailed in at action stations, with the guns ready to go, should they be needed.

“And then we were confronted with the port. These shipping containers had been stacked two high to form a sort of internal barrier around the port, and on top of them, they had US Marines, and some Australian servicemen, as picquets.

“You could see the Somalis up on the hill. They were a pretty desperate group.

“Everyone was wanting for food and water over there and ‘the rule of gun’ ruled.”

Port defences at Mogadishu, 20 January 1993. Note the Australian troops on the containers. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Armoured personnel carriers from 3/4 Cav arrive at Mogadishu, 20 January 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Mogadishu, 20 January 1993: Tobruk having just arrived from Australia with members of 1st Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR), equipment and supplies. Photo: John Perryman

Tobruk moored at Mogadishu in 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

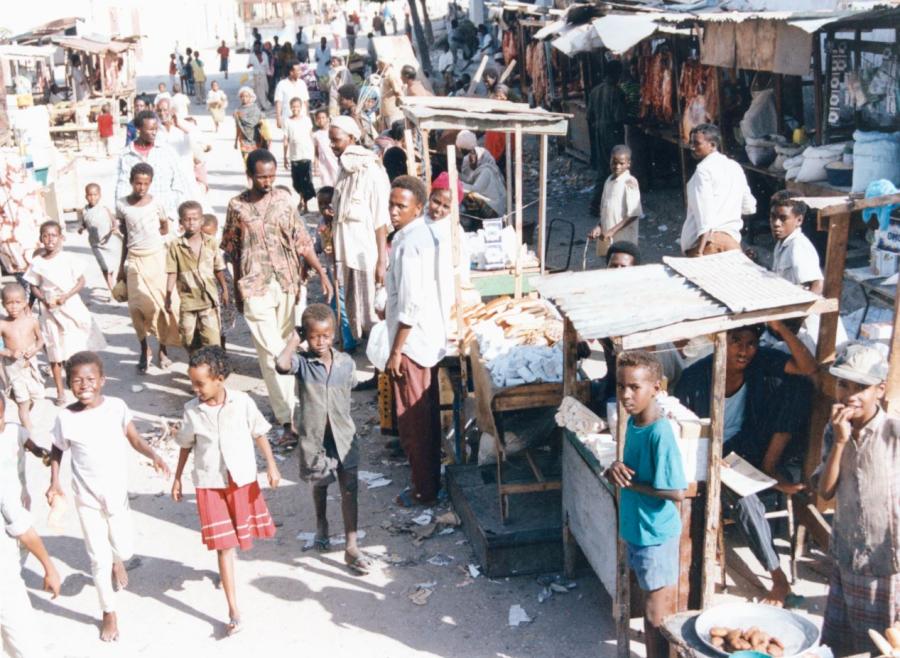

He recalls travelling into Mogadishu with a military police patrol.

“We went through the Bakara markets, which was a bit of a hotspot, and I remember they had these axe handles and large sticks in the back of the Landrovers,” Perryman said.

“We were wearing flak jackets and helmets, and we had to have side arms and things like that. But then they said, ‘If anybody makes a grab at the vehicle or any of your personal gear, or if anyone makes an attempt to get in the vehicle, pick up these axe handles, and don’t hesitate, lay into them, and let them have it, and we’ll tell you when to start shooting.’

“It wasn’t uncommon for people to mob a vehicle and try and grab whatever they could so we were glad to see they were armed with Steyrs and sub-machine guns and things like that like, but we were like, ‘Oh, okay. This all sounds suddenly a bit serious.’”

Somalia humpies, Mogadishu, February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

A displaced persons camp in Mogadishu, February 1993. Phot: Courtesy John Perryman

The site of a mass grave with internally displaced persons living alongside it, Mogadishu, February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Tobruk crew members ashore with the Australian Army in February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

He remembers being confronted by the sight of a mass grave as the convoy passed by.

“You knew you were coming up to something bad before you got there because of the stench,” he said. “You could almost taste it ... There was that much death.

“The stench was absolutely overwhelming. And right next to it, there were these displaced people, living in these little humpees made out of whatever they could get their hands on ... They were like little igloos and that was where they lived ... They had tarps, bits of plastic, anything they could get their hands on.

“And if somebody stumbled across something they felt might be valuable – wire, nails, anything – it was sold in the Bakara markets for food.

“Water was a precious commodity and they had few possessions – few items of clothing, nothing to drink, and certainly no hope, at least not until we got there.

“And that's the one thing that I think Operation Solace did bring ... it did provide a glimmer of hope.”

February 1993: A market in Somalia. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Humanitarian aid being collected from Mogadishu port in February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Over the next five months, Tobruk conducted continuous resupply runs, carrying building materials and humanitarian aid supplies between Mogadishu and Mombasa in neighbouring Kenya.

“We had control of the seas around Mogadishu ... and the aid was getting through ... But we were always on this clock that was running down. What happens when we pull out? And, history of course tells us that when we pulled out, there was a vacuum, and it all went back to hell.”

When Perryman returned to Australia, he found it difficult to settle down.

“It was very much in my mind for that first six months afterwards,” he said.

“When I got back, I looked around, and it was interesting to see people complaining about who left their dirty coffee cup on the bench, who didn’t put the paper in the photocopier, and it took me probably a good six months to come back down to earth ...

“Life went on ... and it didn’t seem to me that a lot of people even remembered that we’d gone.

“Tobruk had sailed over the horizon months before and this had all happened a long way from Australia ... and we all got a gong, and that was it.”

Shipmates ashore with Australian Army MPs, Mogadishu, February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Perryman beside a Somali MiG-21MF 'Fishbed J' fighter, Mogadishu, February 1993. Photo: Courtesy John Perryman

Thirty years later, Somalia veterans have been recognised with a Meritorious Unit Citation and a photographic exhibition at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Perryman was one of more than 120 Somalia veterans who led the Anzac Day Veterans’ March with Governor-General David Hurley, who commanded the 1RAR Battalion Group during Operation Solace.

“To me, Operation Solace was the high water mark,” Perryman said.

“And I did feel that we were making a difference.“We were a long way from home ... and it really did seem like [the Wild West].

Perryman, left, with Commander Kevin Taylor in Mogadishu. Photo: AWM P01914.013

Unloading at the port in Mogadishu, January 1993. Photo: John Perryman/AWM P01914.007

A truck belonging to a United Nations relief convoy leaving the port area loaded with bags of food from a relief ship. Photo: John Perryman/AWM P01914.020

"There was a complete breakdown of law and order and society and the feeling in Mogadishu was tense and unpredictable. You never quite knew what was going to happen. It was quite sporadic and spontaneous and there was no great warning …

“It was the madness of Mogadishu. And it really was madness. It was the maddest, weirdest place I’ve ever been, and I have no desire to go back there at all. If somebody said, ‘Let’s go back to Mogadishu,’ I would be like, ‘I don’t think so.’

“I’ve relived it all so many times in my mind. I remember the heat, the dust, the wind, the grit in your eyes ... and even telling the story of the mass grave, I can still smell it.

“I’ll never forget it.”

Perryman in Somalia in February 1993. Photo: AWM P01914.015

Defence All-hours support line – The All-hours Support Line (ASL) is a confidential telephone service for ADF members and their families that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week by calling 1800 628 036.

Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling Service provides free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. They can be reached 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit the Open Arms website for more information.

DVA provides immediate help and treatment for any mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. If you or someone you know is finding it hard to cope with life, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254. Further information can be accessed on the DVA website.