Under the Kaiser's Crescent Moon

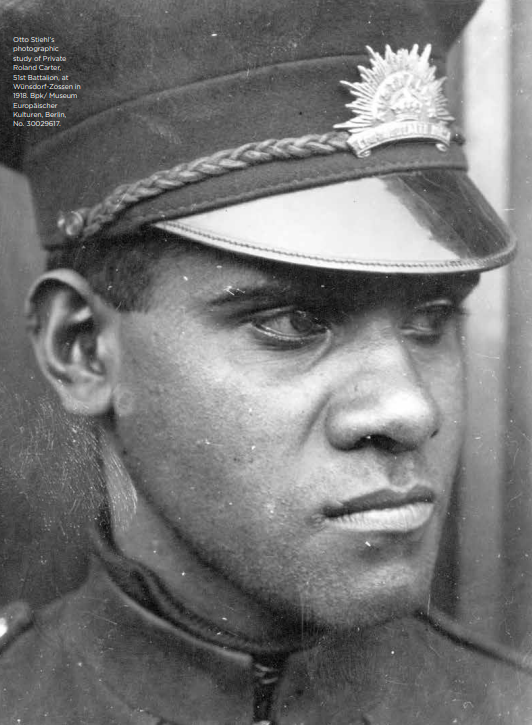

Otto Stiehl’s photographic study of Private Roland Carter, 51st Battalion, at Wünsdorf-Zossen in 1918. Bpk/ Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, No. 30029617.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following post contain the names, images and objects of deceased people.

A large wooden mosque that once stood 40 kilometres south of Berlin illustrated the global reach of the First World War. Built between the villages of Wünsdorf and Zossen in July 1915, it was the first mosque on German soil and formed the centrepiece of a special prisoner-of-war camp that sought to destabilise the imperial control of Britain and France. By 1916, the camp held more than 4,500 Muslim and colonial troops from British India and Egypt, and from French North Africa, who were granted the freedom to practise their faith in quiet and picturesque surroundings. In addition to the mosque, the prisoners were provided with spiritual texts, were allowed to observe Ramadan, and had a regular program of sermons from visiting spiritual leaders. This so-called Halbmondlager (a “crescent moon camp”, referring to the Islamic symbol) for French and British prisoners at Wünsdorf–Zossen, and another for prisoners from the Russian Caucasus at nearby Weinberg, were the only camps of their kind among the 172 prison camps in Germany at the end of the First World War. By treating Muslim prisoners well and cultivating an appearance of religious freedom, the German authorities hoped to convince the prisoners to wage a holy war against their oppressive colonial masters. It was an unlikely place for two Indigenous Australians captured on the Western Front to spend the last year of the Great War.

The idea behind Germany’s “jihad experiment” originated with the German diplomat, archaeologist and aristocrat Max von Oppenheim, who had studied Arabic and Islam in Egypt, travelled extensively throughout the Ottoman Empire, and had a posting at the German Consulate General in Cairo in the years before the war. When war was declared, Oppenheim returned to Germany as an expert on the Middle East, whereupon he prepared a brief on revolutionising the Islamic territories of Germany’s principal enemies. To do this, Germany would rely on the Ottoman Sultan to call on the world’s Muslims to engage in a holy war against Britain, France and Russia.

Oppenheim’s plan came to fruition in October 1914 when the Ottoman Empire entered the war as an ally to Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With mounting pressure from Kaiser Wilhelm II, Sultan Mehmed V appealed to the Ottoman Empire and to Muslims across the world to support the Ottoman war effort and its allies in what he declared to be a holy war against the Entente.

Ritual foot washing before prayer at the WünsdorfZossen camp. Bpk/ Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, No. 00070116

Oppenheim was appointed head of the newly created Intelligence Bureau for the East and was involved in the establishment of the Halbmondlager at Wünsdorf–Zossen outside Berlin. This came about after German troops captured tens of thousands of French, Russian and British prisoners in the opening engagements on both the Eastern and Western Fronts. Not only would the camps at Wünsdorf– Zossen and Weinberg serve to recruit volunteers for the Sultan’s jihad against Germany’s military enemies; the Halbmondlager, with its ornate wooden mosque, became a special propaganda camp to show the rest of the international community that Germany was treating prisoners fairly and in accordance with international law. In the end, as many as 3,000 Muslim prisoners were recruited from the camps and shipped off to Baghdad, where they went on to fight on the side of the Central Powers on the Mesopotamian and Persian fronts. But plunging morale and revolts within their ranks suggested scepticism about a jihad against the western world that really applied only to Britain, France and Russia. As well as failing to recruit prisoners to fight a targeted holy war against their former armies, Oppenheim’s experiment failed miserably in its attempt to destabilise the Entente’s colonial control.

The Halbmondlager remained active for the rest of the war, although it was not strictly a camp for Muslim prisoners of war. By mid-1917, the camp contained Chinese and Vietnamese who had been lumped in with French colonial prisoners – among them Moroccans, Algerians, Tunisians and Senegalese. Sikhs, Hindus and Punjabis of the British Indian Army shared quarters with Nepalese Ghurkhas, Afghans and men from the British West Indies; they joined smaller numbers of Canadians, Newfoundlanders and British prisoners of war who were moved there towards the end of 1917. At the time of the armistice, Wünsdorf– Zossen held about 4,000 British and French prisoners, many of whom were assigned to outlying labour camps to help support the German war effort. There were more than 13,400 Russians at nearby Weinberg.

Among the 500 or so British prisoners at Wünsdorf–Zossen in early 1918 were two dark-skinned Indigenous Australians who had the misfortune of being captured in the fighting on the Western Front. Roland Carter and Douglas Grant were among an estimated 1,500 Indigenous Australians to have served in the First World War, including at least 12 with Indigenous heritage known to have endured the privations and uncertainty of life in German captivity. Roland Carter had worked as a labourer in the years before the war and was the first Ngarrindjeri man to enlist in the AIF from the Point McLeay Mission Station on Lake Alexandrina in South Australia. Sailing for Egypt with a reinforcement group for the 10th Battalion in September 1915, he was transferred to the 50th Battalion and went on to fight in France. He was wounded at Mouquet Farm and on 2 April 1917 participated in the ill-fated assault on the village of Noreuil, where he was captured along with 80 other men of his battalion. Nursing a gunshot wound to his shoulder, Carter was treated at a German field hospital in Valenciennes, where it is said he discussed Ngarrindjeri healing methods with German doctors. He was transferred to the hospital at the prisoner-of-war camp at Zerbst on Germany’s Elbe River, and went to the Halbmondlager at Wünsdorf– Zossen around November 1917. Carter may have crossed paths with Gordon Naley, another Indigenous Australian captured in France, who also passed through Valenciennes and Zerbst.

Some anthropologists considered a visit to Wünsdorf-Zossen “as worthwhile as a trip around the world”.

Douglas Grant arrived at Wünsdorf– Zossen not long after Carter. As a baby, Grant had been rescued by two members of a collecting expedition from the Australian Museum following a massacre in south-west Queensland. He was adopted by one of the collecting party and raised no differently from his white foster brother. Grant attended school in Sydney, trained as a draughtsman and worked for several years at the Mort’s Dock & Engineering Company before leaving to work as a wool classer on a sheep station near Scone, NSW. Grant was given opportunities available to few Indigenous Australians at the time. He could recite Shakespeare and was a particularly good penman; he carried his foster-father’s thick Scottish brogue and was known to play the bagpipes exceptionally well. Grant enlisted in the AIF in January 1916 but was delayed from embarking as a result of regulations that prevented Indigenous Australians from leaving the country without government approval. He later sailed for England with a 13th Battalion reinforcement group and proceeded to the fighting on the Western Front. Grant joined his battalion in the line near Gueudecourt and fought his only action on the Western Front at Bullecourt on 11 April 1917. Wounded by grenade fragments, he was among the 1,170 Australians of the 4th Division taken prisoner that day. Grant passed through a field hospital, was transported to Dülmen in the Rhineland, then assigned to a labour camp near to Wittenberg. He was then transferred to the Halbmondlager near Berlin around January 1918.

By the time Carter and Grant arrived at Wünsdorf–Zossen, the camp was receiving its fair share of visitors from the German scientific community. The exotic mix of prisoners within a short distance of Berlin’s universities gave anthropologists the rare opportunity to study non-Europeans on European soil. Some considered a visit to Wünsdorf-Zossen “as worthwhile as a trip around the world”. With support from the German army and a variety of government ministries, a steady stream of researchers, artists and photographers visited the camp to study the ethnic diversity of the allied prisoners of war, who represented the far reaches of the British and French empires. One project was the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission, led by philosopher and psychologist Professor Carl Stumpf and linguist Wilhelm Doegen, whose teams visited Wünsdorf–Zossen to record dialects as prisoners sang folk songs and read Bible verses and excerpts from literary works. The project made over 7,500 recordings on shellac records, wax cylinders and tapes that are today held in the sound archive at Humboldt University in Berlin. The archive is currently digitising the collection to make each recording available to the public via its website over the course of the First World War centenary.

Private Douglas Grant, 13th Battalion, as photographed by Otto Stiehl at WünsdorfZossen in 1918. Bpk/ Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, No. 30029794.

One German researcher associated with the Prussian Phonographic Commission was Leonhard Adam, who first met Douglas Grant at Wünsdorf– Zossen and recalled him as an avid reader of English literature. Having been raised by white foster parents, Adam said, Grant “was unable to give me any information that we did not already know” because “his attitude to his own people was exactly that of a white person”. Neither Grant nor Carter was recorded by the Phonographic Commission, but each had his portrait taken by photographer Otto Stiehl and may have sat for Thomas Baumgartner and Max Beringer – two promising portrait artists known to have painted allied prisoners in camps near Berlin. Grant is said to have sat for renowned sculptor Rudolf Marcuse, who was invited to make portrait busts of “interesting types in the camps”. Marcuse later fled to England to escape the Nazi persecution of European Jewry and took his collection of works with him. There was a rumour that his bust of Grant had been donated to the Imperial War Museum in London, although there is no evidence that this ever occurred. The whereabouts of Marcuse’s bust of Douglas Grant, if it exists, remains a mystery.

In spite of the revolving door of scholars and artists, the prisoners at Wünsdorf–Zossen enjoyed a remarkable sense of freedom both inside the camp and out. In a letter home in March 1918, Carter described being in “fairly good health” and receiving “good treatment” from the German camp administration. Christian prisoners attended regular church services, which Carter “liked very much”, and were given parole outside the camp if they promised not to escape. “I went in the town to see the moving pictures,” Carter wrote. “All the Native prisoners of war went.” Another Australian prisoner remembered Grant being given the freedom of visiting Berlin, where “being black, he couldn’t get away”. As well as visiting local museums, it was said he was “photographed and his skull measured” at one of Berlin’s universities. “He was measured all over and upside down and inside out … he was the prize piece, the prize capture.”

Captivity could be stifling and oppressive, and prisoners never knew when it all might end – uncertain when, or if, they would ever see their loved ones again. German scholars viewed Douglas Grant as an object of curiosity, but it is important to remember that he remained autonomous in captivity and retained a sense of pride and regimental bearing. His story best illustrates how some prisoners in the First World War coped with the stresses of confinement by dedicating their lives to the welfare needs of other prisoners. Not long after arriving at Wünsdorf–Zossen, Grant started work in the parcel room and distributed all incoming mail, food and clothing parcels addressed to British prisoners in the camp. He was also elected president of the British Help Committee, which received regular consignments of food and clothing parcels to assist prisoners not in contact with the Red Cross. The prisoners most needing help were a group of Sikhs, Hindus, Punjabis and Ghurkhas who were sent to work in the potash works at Steinförde bei Wietze, over 150 kilometres away. Working through a civilian internee who could translate the prisoners’ requests into both English and German, Grant ensured the men received regular supplies appropriate to their religious customs. The most significant tradition among the Muslim prisoners was Ramadan, which was observed among prisoners at the potash works at Steinförde bei Wietze throughout June and July 1918, thanks to Grant’s efforts.

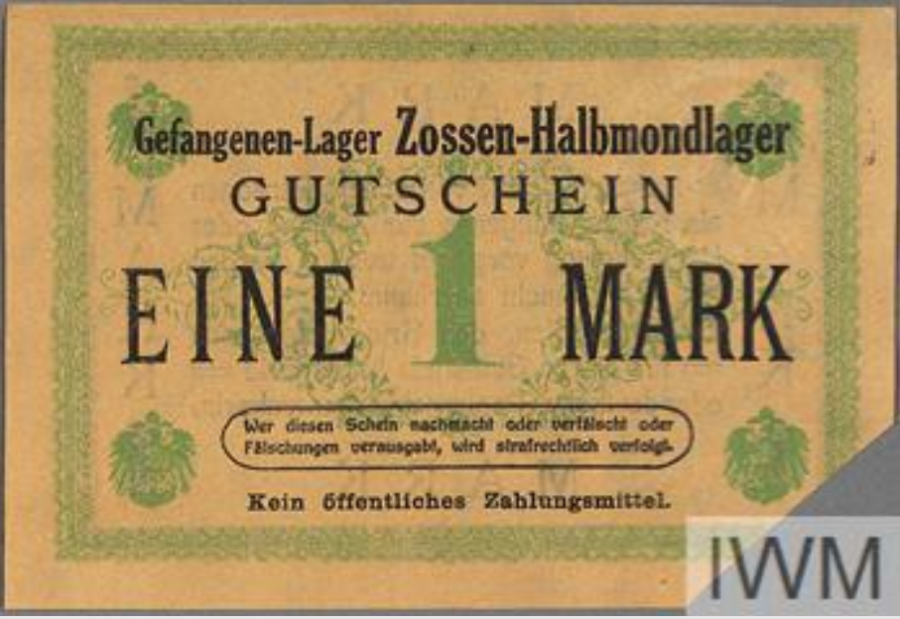

German prisons issued their own currency, which was not valid elsewhere, to stop prisoners buying items from German civilians when they were in town. IWM CUR 18384.

After the armistice, Carter and Grant were repatriated to England and returned to Australia, where they were discharged from the AIF. Carter returned to the Ngarrindjeri people on the Point McLeay Mission Station near Lake Alexandrina (today known as Raukkan), and Grant to his former employer at Mort’s Dock & Engineering Company in Sydney. Grant began lobbying for Aboriginal rights and was active in returned servicemen’s affairs; he even conducted a regular session on a local radio station. But following the deaths of his foster parents and siblings, he suffered rejection and frustration on account of his race, in spite of adopting white culture. He lived and worked at the Callan Park Psychiatric Hospital for many years and died on the Aboriginal reserve at La Perouse in 1951 in relative obscurity. Grant was a dynamic and intelligent man who spent the latter years of his life irritated and wasted.

There is a serendipitous footnote to Australia’s connection to the Halbmondlager at Wünsdorf– Zossen. Under Nazi anti-Semitic law, Leonhard Adam was stripped of his academic positions and was forced to flee Germany. He sought refuge in England, where he taught at the University of London until he was interred as an “enemy alien” in 1940 and sent to Australia with 2,500 other Jewish refugees. Adam was imprisoned at Tatura in Victoria until 1942, when he was given parole to the National Museum of Victoria and granted residence to study the Aboriginal use of stone under Professor Max Crawford at the University of Melbourne. Adam went on to become an eminent scholar, lecturer and part-time curator of one of Australia’s largest ethnographic collections, and succeeded in rekindling a friendship with Roland Carter that stemmed from his days working with the Prussian Phonographic Commission. Carter was ecstatic: “I cannot find word good enough to tell how delighted and overjoyed I was to hear of you my dear friend,” he wrote in 1947. “I am going to try my hardest to come over to see you … I am only a War Pensioner but I think I can save up enough for me and my wife to make the trip [to Melbourne].”

It is widely known today among Raukkan’s Indigenous community that farm land surrounding the Point McLeay Mission was purchased by Leonhard Adam and bequeathed to the Ngarrindjeri people. It is land still cultivated in the memory of an unlikely friendship that began in an unlikely prisoner-of-war camp on the other side of the world over a century ago.

This article was originally published in Issue 76 of Wartime magazine.