Keeping in Contact

“I can’t believe you are away again.” Kathy Swinden wrote these words to her husband, Lieutenant Commander Greg Swinden, in October 2001. It was the third time in eighteen months that Greg had been deployed and separated from his family.

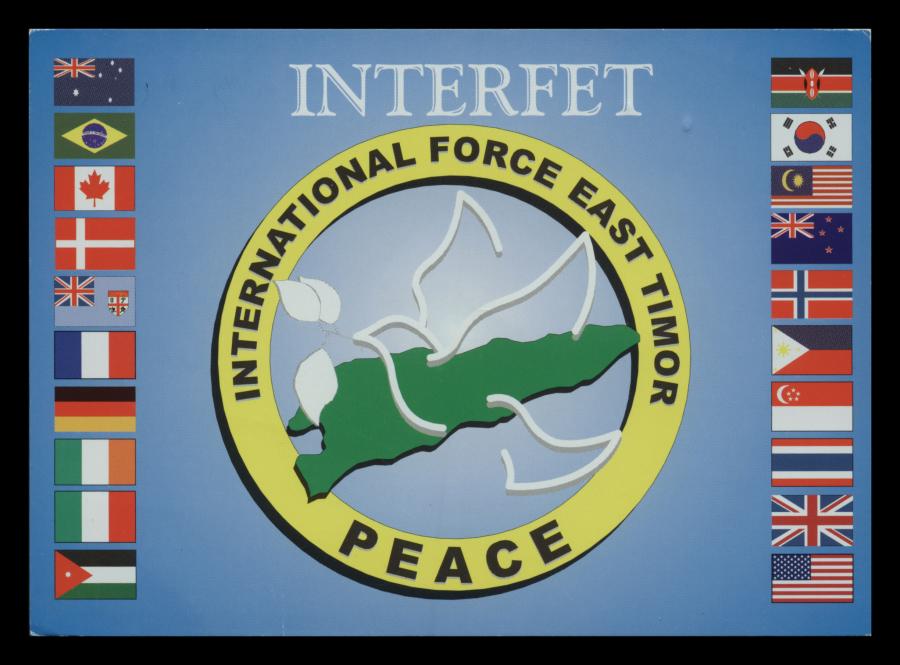

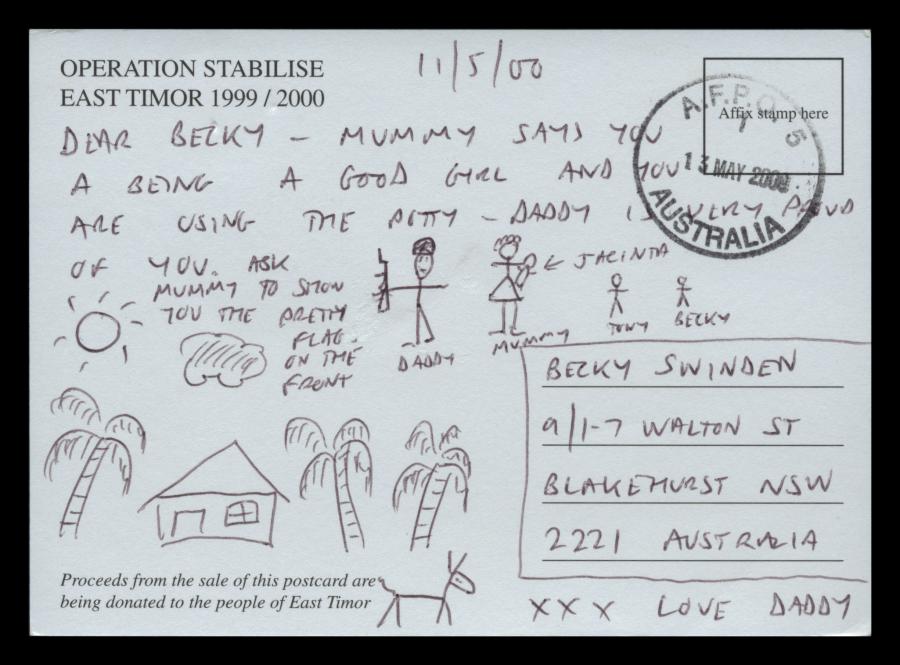

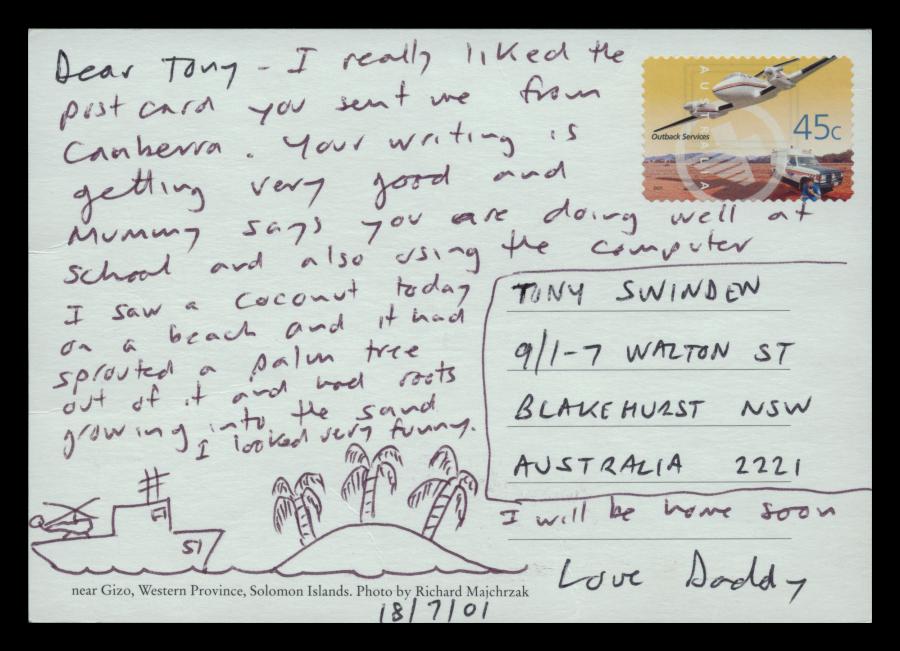

With Kathy and their three young children at home, Swinden had to think up creative ways to stay connected. He sent 46 postcards during his deployments to East Timor, the Solomon Islands and the Persian Gulf. He wrote to each of his children, remarking on the animals in Timor, of building a playground in Port Vila, and of riding a camel in Dubai. He also sent postcards covered in rough drawings of palm trees, ships, helicopters, animals he had seen, and even of himself with the family and their dog.

One of the postcards Swinden sent to his eldest daughter, Becky, from East Timor in 2000.

The postcards were a way for Swinden to remain connected with his children, to let them know that he loved them and was thinking of them. And it worked, too. “The kids have been very impressed with all the postcards”, Kathy informed Greg in January 2002.

A postcard sent by Swinden to his son Tony during his deployment to the Solomon Islands on Operation Trek in 2001.

Communication with loved ones has always been important to Australians deployed overseas. This is because letters, drawings, packages and postcards—anything with words typed or etched across a surface—represent attempts to maintain contact and sustain relationships, despite the distance that separated them from family and friends.

Communication has been improved in the digital age with the development of new technologies, which allows families to remain connected through phone calls, video chats and instant messages. Trooper Richard Lalich, for example, sent group emails as a way to keep family and friends updated during his deployment to Iraq in 2006–2007. The means of communication, however, have not always been so rapid. Australians have had to be innovative in order to correspond and maintain connections in wartime.

During the First and Second World Wars, Australians were prolific letter writers. They had to be to remain in contact, due to the sheer distance between Australia and the war fronts. Postal services, though, were slow and sometimes unreliable. The volume of mail sent to Australia from loved ones overseas, coupled with the restrictions on shipping, meant that it took weeks, sometimes months, for mail to arrive. If it did at all. At least one set of letters between Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel and his wife Sibyl during the First World War was lost when a transport ship was sunk. But this did not stop some from writing almost daily.

Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel by W.B. McInnes

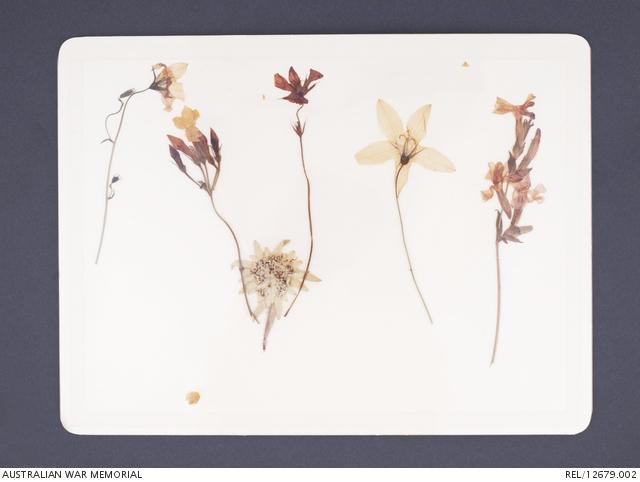

Sir Harry, the senior Australian officer in the Sinai and Palestine campaign, wrote hundreds of letters to Sibyl during the war. He describes life and conditions in Egypt, on Gallipoli and in Palestine, and remarks on friends and acquaintances. Simple information exchange like this enabled the couple to keep abreast of one another’s lives. Sir Harry, though, went to greater effort to maintain intimacy. He began every letter with “My Dear Little Sweetheart” and often sent home pressed flowers he had collected during his travels through the desert. Small tokens such as these were enough for Sir Harry to show affection to Sibyl, in spite of the time and distance they remained apart.

Pressed flowers, similar to those collected and sent by Sir Harry to Lady Chauvel

For others, efficiency was key. In 1942 Gunner Leonard “Paddy” McLaren wrote a 5-page epic to his sister Gwen. He tells of his experiences during the disastrous Battle of Crete, the capture of his regiment by the Germans, and of his escape from captivity – with a small group of others, he broke through the barbed wire, hid among the locals and, later, stole a boat and sailed for Egypt. The tale ends with McLaren asking Gwen to circulate the letter “to all & sundry & save me the trouble of writing one to each & all of the family.”

It was not uncommon for letters to be shared among family and friends. That way, everyone had the latest news and could feel connected. Indeed, during the Boer War letters sent home were often published in newspapers for wider dissemination. One letter from Private John Jennings of the Victorian Mounted Rifles, describing a fierce engagement near Colesberg, was published by a friend in the West Australian newspaper in March 1900. The friend, T.E. Lilleyman, failed to consult Jennings beforehand, but was courteous enough to send him a clipping of the article!

Jennings with fellow members of C Company, 1st Victorian Mounted Rifles in 1899

This kind of group communication has also been an effective way to link contingents of deployed personnel with those at home; to create a shared community.

Alma Saw did exactly that through the “Adopt-A-Soldier” initiative. When Saw’s son, Corporal Shane Alloway, deployed to Somalia in 1993, Saw was concerned that some of the soldiers were not receiving enough letters or contact from Australia. With the help of her daughter Corina and the Capricorn Coast Mirror newspaper, Saw appealed to her hometown of Yeppoon in Queensland. “The soldiers in Somalia are feeling down”, Corina wrote, “How about you write a letter to the soldiers without much mail.” The initiative was a success, with ordinary citizens writing with enthusiasm to the Australian troops in Somalia.

Corporal Shane Alloway (right) disembarks at Mogadishu, Somalia in January 1993

Saw created a shared sense of community between Yeppoon and the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. The “Adopt-A-Soldier” initiative was effective because it was a way to link the soldiers with Australia and to let them know that their efforts were appreciated and worthwhile. As Alloway wrote to his mother, “I’m so proud of the work you have done … Everyone here cann’t [sic] get over how much yourself and the town is behind me and it makes our time here better.”

Although some of the methods have changed over time, effective communication has enabled Australians to maintain connections with family and friends while deployed overseas. For this reason, letters, postcards, emails and drawings are often treasured items – valued by families, archivists and historians alike for what they tell us about the people, their lives, and how they kept in contact.