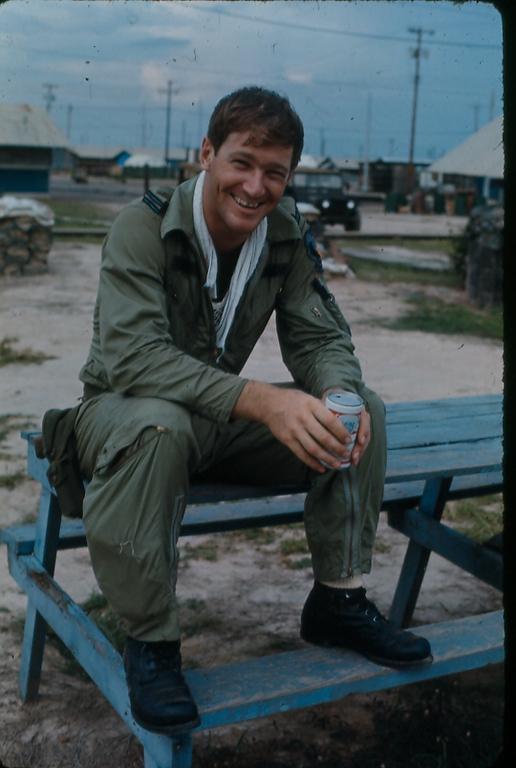

'You had a job to do ... and you did it to the best of your ability'

Ken Semmler always wanted to fly. As a boy growing up in South Australia, he surrounded himself with model aircraft and developed a love of flying that would stay with him forever.

He became a fighter pilot in the Royal Australian Air Force and was one of 36 Australians who flew close air support missions with the United States Air Force during the Vietnam War.

One of the aircraft he flew – the OV-10 Bronco 67-14639 – is now part of the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, and has been painstakingly restored by Memorial conservators to look as it did during the war.

“The OV-10 was just a delight to fly and to restore it means a lot, it really does,” he said. “We’re not many in the vast sea of thousands who participated during the war, but if we can convert that into something which people can prod, and poke, and read stories of, then that’s pretty special … It’s part of a living history, and it’s very precious.”

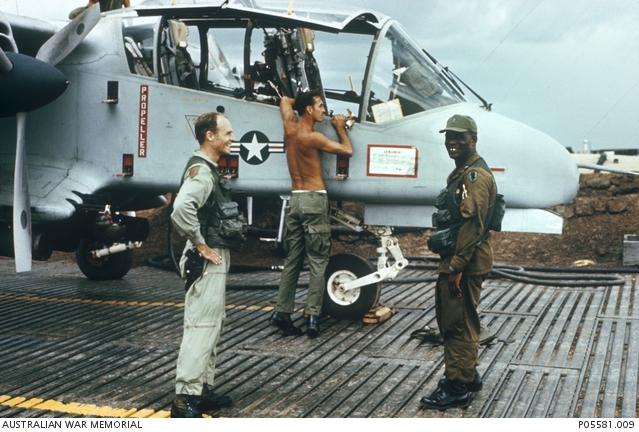

Flight Lieutenant Ken Semmler, right, climbing into the cockpit of an OV-10A Bronco aircraft, possibly 67-14619, from the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron, United States Air Force, based at Cu Chi. He is being assisted by Sergeant 'Tank' Wherret, left, USAF.

Ken’s own journey to become a self-confessed “jet jockey” began when he was just child.

“I grew up on a farm in the Barossa Valley and I had a great love of aircraft,” he said. “My bedroom was a little ‘sleep out’ on the house, and how I actually got into that room and out of it I don’t know because it had that many balsa aircraft models in it.”

He joined the Army cadets at high school in Nuriootpa, and considered joining the Army, but it was his love of aircraft that would have the biggest influence on his eventual career choice. “I thoroughly enjoyed it, and was very much attracted to the military, so I thought I’d like to have a go at that. But then I thought, hang on, wait I minute, I want to fly those funny, heavier-than-air machines.”

At 18, Ken joined the air force and realised his dream of becoming a pilot. “I survived the training and to my surprise was posted to fighters, where we converted onto the Sabre,” he said. “The conversion was rather high speed, so it’s a wonder we survived it, but we did, and our group went off to Darwin to practise holding back the invading hordes which of course didn’t happen, thankfully. From there, it was on to the Mirage, and I was privileged to be with the first Mirage squadron – Number 75 – to go to Butterworth in Malaysia.”

An OV-10A Bronco twin engined aircraft, 67-14619, from the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron, United States Air Force, flying over a province in South Vietnam. The aircraft is armed with four rocket pods (visible under fuselage) and four 7.62 mm M60 C machine guns. Each rocket pod holds seven 2.75 inch rockets.

It was then that he became interested in training to become a forward air controller, or FAC as they were known. “I just about got writer’s cramp applying for the job,” he said. “But I eventually got the slot, and at the beginning of 1970, I went up to Vietnam, just by myself, and that was my first meeting with an OV-10 Bronco.”

He spent a week at Da Nang learning how to fly it, and then went to work; first with the US 25th Division, based at Cu Chi, about half way between Saigon and the Cambodian border; and then with the 1st Air Cavalry Division in Bien Hoa.

Although forward air controllers were posted to USAF squadrons controlled by the Tactical Air Control Centre in Saigon, they usually worked from forward locations where they were quartered with the Army units they supported.

As ‘on scene’ air commanders, they flew small fixed-wing aircraft at low altitudes, providing immediate fire support to troops on the ground, marking targets, directing air strikes and artillery bombardment, and carrying out visual reconnaissance.

“The OV-10 was just a brilliant aeroplane for the job,” Ken said. “When there was a fight going on, the FAC was the onsite controller of all that happened; no air strike went in in South Vietnam unless it was under the control of a FAC, and that was day or night … so we were able to use the aircraft to its hilt.”

An OV-10 'Bronco' aircraft with one engine running on the tarmac at Di An, home of the US 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division.

Mission preparation was extensive, with briefings about troop positions, call signs, radio frequencies and tactical plans.

“Before each trip, you went into the joint army/air force group, and said, ‘Where are our troops, what are they up to, and what are they expecting to happen today?’ But very often the unexpected happened – not the expected – so when the bad guys started shooting at them, or vice versa, you’d get called up by your company commander, and they’d say, ‘We’re taking whatever fire and we’re about to pop smoke,’ so that you could identify exactly where they were; but they would never say they were going to pop grape or blue smoke because very often the North Vietnamese Army were listening in and they would pop the same colour to try to confuse matters. You could then pinpoint where they were, and whistle up the fighters, and brief them on the target and what was happening.”

During an attack, the FACs would fly in a “racetrack pattern” to one side of the target so that they were able to keep the target, as well as the friendlies and the fighters, in sight while controlling the various attack runs.

“You might have three, or at the maximum four aircraft, in a flight, and you’d ride shotgun, so that you could correct them as they came in,” Ken said. “And that’s where the OV-10 was brilliant; it had excellent vision, and vision was one of the keys, so it was very, very good. There were very few blind spots, and you could follow the lead aircraft in visually until you were ruddy sure that he wasn’t about to drop anything over the friendlies.

“The fighters and the artillery would do their stuff until the contact had been broken, and if the friendlies had taken any casualties you would provide cover for the medevac choppers to come in. You would use the cannons on your fighters to keep the bad guys occupied so that the choppers could get in and out without being severely air-conditioned with ruddy AK; and then you would do a bomb damage assessment, and go down over the trees, and have a look and see whether you could see anything.

“Sometimes you would have secondary explosions, and you would think, ah, what have we got here? Someone’s been making gun powder or storing it there.”

The view from an OV-10A Bronco aircraft from the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron (19th TASS), United States Air Force (USAF), during an air strike against the NVA.

The work was demanding and often dangerous.

“It was a pretty hairy job, in all honesty, but to counter that, you got to be sneaky, and you learnt how to think with the mind of the opposition; it was a game of patience – patience and cunning,” he said.

“When you were out looking for something, the safest place to be was on top of the treetops because if there were a bunch of NVAs sitting out there cleaning their AK-47s and having a cup of tea, and suddenly they heard this aircraft approaching, they knew what it was.

“If you were on top of the trees, you could pass by before they could have a decent shot at you, but if you were between the tree-top level and 1500 feet you were just asking for trouble because they had plenty of time to aim and fire at you.

“Of course it had its limits, and that’s where the Bronco’s bulbous canopy helped; you could look straight down, and get sneaky. Provided you had a clear run ahead, you could look behind you as you were flying over and that was when bad blokes would stand up, and that was a very foolish thing to do because then you knew exactly where they were.”

Bronco

The forward air controllers also came to know the landscape and would notice any changes in the environment that could help give away enemy positions.

“We were given an area of operations, and it’s not an exaggeration to state that one came to recognise individual trees as you observed what was happening on the ground,” he said. “If you saw tracks through the jungle, you would keep your eyes on them, and over a couple of days you could build up a picture of what was going on. You might then say, ‘All right, we think there is a bunker or a supply complex there, we’ll put in some pre-planned strikes,’ and that was really one’s trade.”

Radio work was also a vital part of the forward air controller’s job and it took considerable skill to master.

“That’s where the OV-10 was very well equipped,” Ken said. “We had two fox mike radios: one which you used to talk to army command on the ground, which was vital; and one which you used for artillery control. You also had a UHF set, which was for your air-to-air communications with other aeroplanes; a VHF set, which was our direct line to our headquarters from our base of operations; and a HF set as well.

“The four different types were basically used all at the same time, and that’s why one of my really good mates, Ray Butler, said to me, ‘Look, flying the aircraft is easy, it’s the radio work that’s difficult.’

“But I didn’t mind. I used to try and get flights on Saturday nights because then we could tune in to Radio Australia and get the footy scores. Then on Sunday mornings I’d tune in to the Lutheran hour with Dr Oswald Hoffman and hear part of a worship service. I always remember one Sunday morning, it was beautiful; there were just a few light clouds, and the sunshine was lovely. I was minding my own business looking under trees with one ear to the worship service, and then a pretty big fight began so I had to go to work and help sort that out, but it always sticks in my mind: the contrasts with which one dealt.”

A United States Air Force North American Aviation OV-10A Bronco aircraft, with a red and yellow banded spinner and the tail number 67-14639, on the tarmac at Vung Tau air base, having been unloaded by ground crew. This aircraft, which belonged to the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron (TASS), is now in the Memorial's collection. Behind the Bronco are three RAAF Caribou transport aircraft.

He remembers coming under fire one night when he was returning from Bien Hoa with a New Zealand forward air controller that he worked with in the back seat of the aircraft.

“It was 50-calibre this time – serious stuff – and the rounds went between the cockpit and the engine,” he said. “They missed us, but the Kiwi was shouting at me, and I couldn’t hear anything that he said because the intercom was broken.

“We got to Cu Chi, and, oh dear, that was interesting, there were no runway lights. I didn’t feel like going back to Bien Hoa – I’d had enough for one day – so I decided to see if we could land.

“We knew roughly where the runway was because it was only a little runway, and fortunately the radio still worked, so I got onto our blokes on the flight line. Some ruddy generator had failed and wouldn’t be operational for a while, but I really wanted to get home, so I tried to land once with just a landing light, but I couldn’t pick up the runway enough to get the aircraft down.

“I said to the blokes, ‘Look, if you can park a jeep on each side of the threshold, I’ll see you driving out there, and then I’ll know where the end of the runway is, and I’ll be okay.’ So with a poor frightened Kiwi in the back, who couldn’t speak to me because the intercom was broken, we managed to land and we got home.

“It was probably unwise, and not good for long life or good health, but I got away with it. We all got away with many things.”

Squadron Leader (later Air Vice Marshal) Graham Neil conducting a pre-flight check whilst sitting in the cockpit of an OV-10A Bronco twin engined aircraft.

Flight Lieutenant Keith March talks with Squadron Leader (later Air Vice Marshal) Graham Neil, who is crouching in the cargo area of a United States Air Force North American Aviation OV-10A Bronco aircraft, tail number 67-14639, from the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron. Food supplies are being loaded into the aircraft.

He remembers one particular flight with his friend Squadron Leader (later Air Vice Marshal) Graham Neil. The pair was on a routine visual reconnaissance mission when they were summoned to assist a US armoured convoy which had been ambushed by the NVA. At the same time, four kilometres to the south, a second NVA attack was being launched against a US base camp at Trai Bi.

“A lot of trips I don’t remember, but I remember this one – a lot,” Ken said. “The only contact we had with Australians was when we went down to Vung Tau about once a month to get paid, so Graham and I had gone off with me in the back seat, and we were busy looking under trees when a very solid fight broke out near the Cambodian border.”

While waiting for the requested strike aircraft to arrive, the pair went into action in support of the convoy. They fired high explosive rockets and made strafing runs with their machine guns along the roadside until the enemy broke contact. They then provided covering fire to allow the US dust-off helicopters in to extract the wounded, before turning their attention to the base camp at Trai Bi. Using their remaining ammunition to suppress enemy positions in a treeline west of the camp, they called in two more OV-10As that were close by and directed them onto the targets. The attack aircraft arrived shortly after and were directed onto the targets too, co-ordinating their passes with US helicopter gunships.

With their OV-10 running very low on fuel, they called in a new FAC to take over, so they could land at the nearest airfield, Tay Ninh West, and refuel. For their actions that day, Graham was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross as well as the US Distinguished Flying Cross; Ken was Mentioned in Dispatches for another mission and awarded the US Distinguished Flying Cross.

Squadron Leader (later Air Vice Marshal) Graham Neil, left, 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron (19th TASS), United States Air Force (USAF) speaking to the pilot of a US Army O-1 at the USAF base at Tay Ninh West in South Vietnam. He had directed Ken and Graham onto a group of NVA heading for the Cambodian border after their attempt at ambushing the convoy North of Trai Bi. He also flew to Tay Ninh West to refuel.

Squadron Leader (later Air Vice Marshal) Graham Neil in front of an OV-10A Bronco twin engined aircraft from the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron (19th TASS), United States Air Force (USAF) based at Cu Chi. It is fully armed with rockets and the starboard side pair of M60 C machine guns (note the hanging bag) are visible within the fuselage pylon.

Afterwards, they continued on to Vung Tau to pick up their pay and other supplies.

"The domestic issues were very important and our countrymen in Vung Tau used to feel a certain amount of compassion for us living out in the scrub,” he said. “The OV-10 had a magnificent cargo compartment in the back, so while we were there, we’d pick up copious slabs of Vic Bitter and Fosters, frozen mutton, and bread, and anything else that the cook would give us. They were all gratefully received, and while we were there we would also pick up the mail. It was like the pony express – the mail must get through – but by this time, the weather was really bad.

“I was flying us home across to Cu Chi and the weather was absolutely cactus; there was cloud, rain, you name it, and we were flying low. I put all the lights on on the aircraft – the landing lights, you name it – and I said to Graham [later] that our trip home was much more dangerous than anything that we did during the day when we were being shot at. Someone could have thrown a ruddy pushbike tyre in the air and it would have brought us down, but we got back, and the food and the mail got through, and we enjoyed our beer that night.”

He laughs as he tells how they aquired a few creature comforts to help make their lives a little easier.

“I was a good scrounger and I’d go out with a shopping list,” he said, smiling. “I’d pull up and say, ‘Okay, now I’ve got a case of Vic Bitter in the back there; this is what we are after, can you help us,’ and over the months, we acquired various cooking utensils and a freezer.”

Ken Semmler with Mammasan Oke, right, and her assistant Miss Hi looking on. Photo: Courtesy Ken Semmler

They even acquired a hot water service so that they could enjoy a warm shower and provide hot water for ‘Mammasan Oke’ who did the washing and cleaning. Her husband had been killed in the fighting and she cared for her son alone.

“She was a cheerful and kind lady and we looked after her,” Ken said. “Somewhere along the line we noted that much of her happiness had evaporated. Graham managed to find out that her son was ill... He managed to get her son admitted to the Base Hospital for treatment. It was wonderful to see her good humour return, and she embarrassed us with her kindness. It still hurts to wonder what happened to her and her son, but we give thanks for the good times we shared, even in the midst of a war."

He smiles once more as he tells how they acquired an electric frypan which was used to roast the mutton supplied through the Vung Tau contacts. They did all their own cooking with the evening meal often being the highlight of the day, provided the war didn't intervene. He laughs as he tells how he found it difficult to explain to Mammasan Oke what a sheep was and that the best he could manage was to describe a sheep as a sort of wooly goat.

"The preparation of a roast needed coordination," he said. "Every two hours someone would go flying, so if it was two in the afternoon you’d write a note saying, ‘Roast started at 1400 hours; next bloke back at 1600 hours; turn the roast, and put some water and gravy in the thingo,’ and by the evening, provided nothing drastic happened out with the army, we would all sit around and enjoy a wonderful meal together.”

Flight Lieutenant Raymond John Butler, a Royal Australian Air Force pilot flying forward air control missions with the 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron (19th TASS), United States Air Force (USAF) at Cu Chi, being hosed down in front of one the detachment's OV-10A Bronco aircraft. The occasion marked the completion of his tour in South Vietnam.

For Ken, it was a welcome distraction from the business of war. Like many veterans, he found returning home difficult.

“Despite the difficulties of the task, the day I came back from Vietnam was one of the saddest days of my life,” he said. “I’m blessed in that I’m a pretty amenable sort of bloke, I suppose, but I didn’t realise how angry I had become until I got home. I was angry and sort of frustrated … I was leaving when I felt real gains were being made, and it broke my heart subsequently that we left them to their own devices. It was a terrible, terrible betrayal, and the guilt I felt in ’75 when the north took over the south was devastating.

“On Anzac Day we would go to the march and meet up with the South Vietnamese veterans and have a chat … but I had great trouble when I came back from Vietnam and went back to a Mirage squadron.

“It’s difficult to describe, but the thrill of flight, even in a Mirage, is something special. When you’re at 40,000 feet, barrelling along, playing with the radar, and all sorts of rubbish like that, or else down on the weeds – low level – and going like a scolded pussycat, it’s great fun. I loved flying at night too, and that was a great sport, but there’s a big difference between flying an aircraft and flying it well – a vast difference – and sometimes I flew well and sometimes I flew poorly.

“As I hopped out of the aircraft, I would pat the aircraft and say, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry I flew so badly today,’ because I had let it down. I just couldn’t translate from doing something useful back to a practice role, and I had a heck of a lot of trouble doing that.”

Today, Ken is a grape grower in the Barossa Valley. He was delighted to be able to give a Vietnamese refugee his first job in Australia, and for the past few years, has employed a Vietnamese pruning team. A few years ago, the team included a man who had been wounded in the fighting in 1975 and eventually escaped to Australia. One day he brought along photos from his time serving in the South Vietnamese army; the two sat on the back porch together with their photos and their memories.

Ken doesn’t often talk about the war, but he treasures the friendships that he made and the special bond that they share.

“Many of the blokes I served with, I’m not worthy to polish their boots,” he said. “But they’ve become wonderful friends and I know how much I value those friendships.”

Ken Semmler, right, laying a wreath at the Memorial with Graham Neil.

Ken Semmler and his fellow forward air controllers have been instrumental in the ensuring the Memorial’s Bronco restoration project has been a success.

Looking back, he realises how lucky he was during the war.

“I didn’t feel lucky at the time, but I suppose one was in retrospect,” he said.

“I could have come to grief, many, many, many times, either through my own stupidity, or because the opposition was being smarter than I was … but it sort of clarifies the mind to be shot at for a living, and hopefully you shot back more effectively than one was shot at.

“An SAS bloke once said to me, ‘Oh man, we thought we were just bullet-proof,’ but I never thought I was. I was acutely aware of my mortality, but I was there to do a job, and there’s no heroics attached to that.

“Any sane human being would feel frightened, but not generally when you are in the midst of a fight; you are so busy that it is only afterwards that you think: did that really happen?

“One day strangely enough I was scared for no reason. It was a beautiful day – almost a clear sky – and nothing was happening, but there I was flying, looking at the countryside, and I felt scared; scared as billy-oh.

“I always remember that, and I thought, ‘Well, why?’ I don’t know, maybe it was just too quiet, but it was only afterwards that I thought about it.”

More than 40 years later, Ken and his fellow forward air controllers have been instrumental in the ensuring the Memorial’s Bronco restoration project has been a success.

“It’s a miracle that the aircraft actually survived, considering its history, but it’s got a story to tell, and it’s important to share that,” Ken said. “It’s a living artefact and I’m humbled by that … but you had a job to do, and man, you did it to the best of your ability.”

To learn more about the Bronco restoration project, visit here.