'It's very, very special to me: it just gives that sense of peace and calm'

Lady Hicks was just 12 years old when she attended the opening of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra on Remembrance Day 1941.

“There was a big turnout and I still have a newspaper cutting of it somewhere,” she said.

“We lived just the first street along, and at that stage, this was all paddocks, so we saw the War Memorial being built, brick by brick.”

Her father, Norman Swindon, had served on the Western Front during the First World War and was one of the first public servants to move to the fledgling capital.

“He would parade with the AIF every Anzac Day and every Armistice Day, as it was then called, and when [the Memorial] opened on the 11th of the 11th, I was here with my parents, and my father, of course, was marching,” Lady Hicks said.

“It was vastly different and it wasn’t nearly as big an event then as it is now. Anzac Parade wasn’t finished. It was all bush and trees down there; and, of course, there were no lawns here or anything like that.”

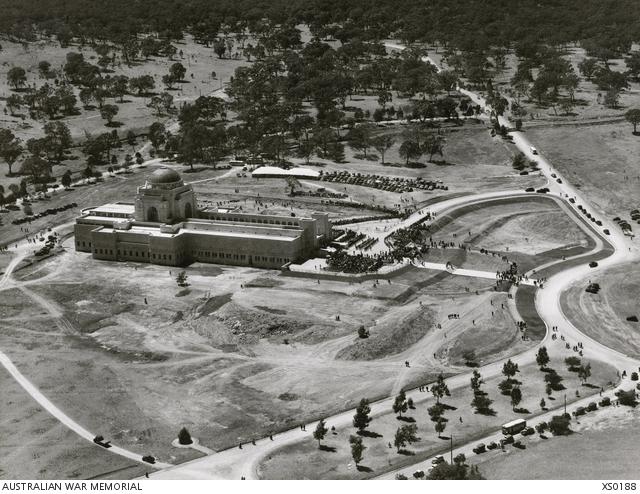

The official opening of the Australian War Memorial on 11 November 1941.

Seventy-seven years later, Lady Hicks was one of 12,000 people who attended the Remembrance Day ceremony at the Memorial and paused for a minute’s silence to mark the centenary of the armistice that ended the First World War.

Wearing her father’s miniature medals, she told how he volunteered for the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915, his parents writing to the then Minister for Defence to give their consent.

“He was 20 and a half when he enlisted … and I still have his diary,” Lady Hicks said.

“He was there from 1915 until 1919, and he was very blessed because he was not wounded at all.

“He was a signaller… His job was laying the lines – the telephone lines – and he had to run along the top of the trenches…

“In his diary, he says how he was walking into Albert [near Amiens] one day with three of his mates, and a stray German shell came over. One of his friends was killed, and one was wounded, but he and the other man were alright – they had survived, but it was quite horrifying.”

First World War veterans marching at the opening of the Memorial.

Her father was one of more than 400,000 Australians who enlisted and were forever changed by the First World War. By the time the guns finally fell silent on the Western Front, 62,000 Australians had been killed and a further 156,000 had been wounded, gassed, or taken prisoner.

The war had left a grim legacy which would reverberate through the generations. But, like many veterans, Lady Hicks’ father never spoke about his wartime experiences.

“I only know where he was through reading his diary,” she said. “He carried it in a little notebook, written in terrible pencil, in his breast pocket, and I wish I’d had it and been able to read it while he was here because I would have asked him lots of questions, but he never spoke about it.“He was in all these horrible places and must have seen a lot of carnage … but he still had a wonderful sense of humour.

“He was getting fairly bald by the end of his time, and he used to say, ‘That’s where the tin hat wore the hair off my head.’”

For her father, Anzac Day and Remembrance Day were particularly important.

“He always marched,” she said. “He was not a tall man – he was only about five foot six – and I think it must have been the last time he paraded: there was a man next to him who was much taller, and who obviously wasn’t feeling very well, so there was Dad, a little short man, holding him up until they could help him … and that’s what it was all about.

“His last parade was on, the 11 November 1978, and he died just a month after that.”

The official opening of the Australian War Memorial on 11 November 1941.

Forty years later, Lady Hicks continues that tradition in honour of her father and all those who have served. Her husband, Sir Edwin Hicks, served during the Second World War, as did many of her childhood friends.

“My husband died as a result of his war service … and I lost a very dear friend with whom I grew up. He was too young to be sent overseas, but he was sent overseas, and after the war, he was being transported home because he’d been injured, but the plane didn’t make it. It wasn’t until 25 years later that we found out what had happened, and where it was, so that was hard too.”

Each Remembrance Day, she pauses to remember them.

“I think of those three people in particular, as well as many, many others,” she said. “Many of the boys who were in high school with me, they didn’t come back, and there’s a long list of them.

“Canberra in the early days was a very close community. If you went to Sydney or Melbourne and saw a Canberra car, you’d know whose number plate it was, and you’d say, ‘Oh, I saw so and so down in Melbourne,’ or ‘so and so was up in Sydney recently.’ There was a real camaraderie between the people, and a great feeling of oneness, so when someone goes, you feel it immensely.”

She still has vivid memories of entering the Memorial for the first time during the Second World War.

“We walked inside and they were playing Handel’s Largo,” she said. “It’s a most beautiful piece, and it’s very, very special to me: it just gives that sense of peace and calm.

“We’re not glorifying the dead here, but we are remembering what they have done so that we can have freedom, and that’s important.”