'We had a job to do and we wouldn’t let any of our crew down'

Laurie Woods always wanted to fly. “Flying is a wonderful thing,” he said. “But when fellas start shooting at you, it’s a different story.”

Laurie, now 95, served with Bomber Command during the Second World War and was one of more than 3,300 Australians who were involved in the D-Day campaign. Seventy-five years later, he is one of only four who are still alive.

“We would have anything up to 500 heavy guns firing away at us,” he said. “And when I say heavy guns, they were using the heaviest shells to get to the height where we were … They were the type of shells that were used for battleship-to-battleship fighting, so it wasn’t a picnic.”

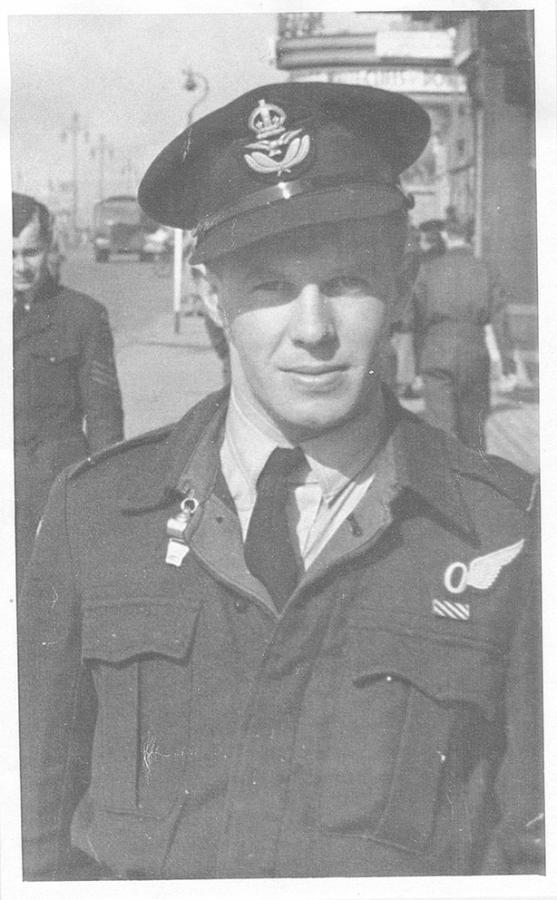

Laurie Woods at Brighton in 1945. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

To mark the anniversary, Laurie donned his old air force uniform and laid a wreath at a Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial to remember his mates who were lost.

“We knew that D-Day was coming, but we didn't know when,” Laurie said. “But someone had to go and sort Hitler out.”

Laurie was a bomb aimer with No. 460 Squadron when Allied forces launched Operation Overlord on D-Day, 6 June 1944, to liberate France and Western Europe from Nazi occupation.

Of the 49 original aircrew posted to No. 460 Squadron with him, only eight men were left alive in October 1944.

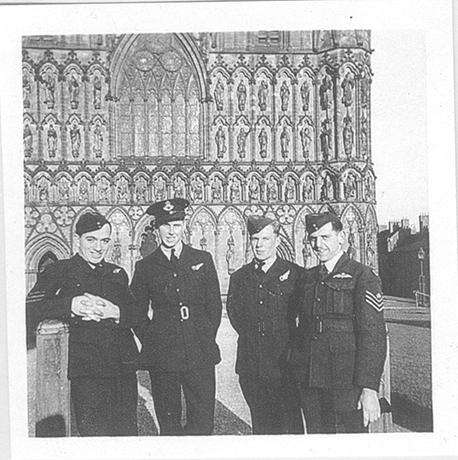

The crew meant everything to Laurie. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

Laurie’s last raid was to Wanne Eikel in Germany on 9 November 1944.

“We were leading 350 Lancasters through this target,” Laurie said.

“I had just dropped the bombs and there was a terrific explosion followed by, ‘Laurie, Laurie, quick.’”

The pilot, Captain Ted Owen, had been hit by anti-aircraft fire and was badly wounded.

“I dashed back … and he was slumped across the controls and we were going into a dive,” Laurie said. “I grabbed the control and held it back until the plane was level again.

“The navigator and the engineer lifted the pilot out of his seat and laid him on the floor … and I set the motors on a revolution of 1300 revs per minute, plus torque boost, which I knew was guaranteed not to harm the motors in under two hours.

“I thought in that time we’d either be back in England, or we’d be crashed somewhere, because that was the first time I’d ever flown a Lancaster.

“I had been in the Boy Scouts and learned from South African scouts, who were visiting Tasmania at the time, how to find direction using only your watch and the sun, so I set course that way before we entered cloud.”

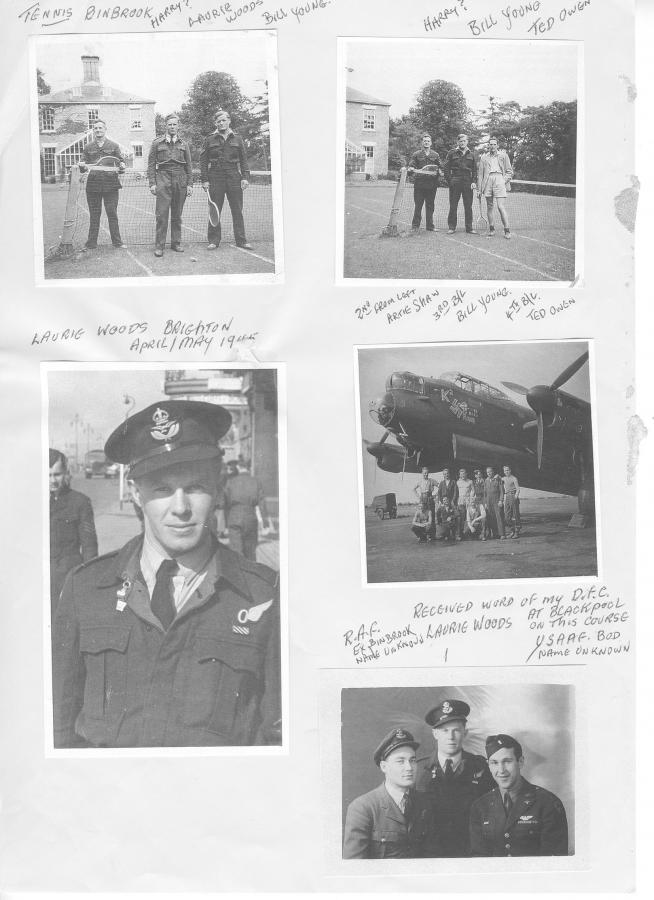

Tennis at Binbrook. Laurie, centre, with Harry, left, and Bill Young. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

Back in England, their Lancaster was reported as having been shot down over the target. It was last seen in a power dive.

“It was very rough, and we were icing very badly,” Laurie said.

“If the plane gets too much ice on it, it will crash because you’ve got no way of preventing it… The mid-upper gunner started yelling out, ‘Hey, we’re icing up badly, better get out of this cloud…’

“We all knew the dangers of it … so I pulled the control, and I flew the plane up out of it, but instead of flying level, it went way over to one side [and was] near enough to crashing.”

Laurie Woods in the United Kingdom during the war. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

Laurie managed to fly the plane above the cloud and eventually requested a fix from the navigator.

“I had to change course – five degrees starboard – and in about five minutes, the Manston Aerodrome, on the heel of England, was showing up,” he said.

“I had been thinking about the crew, and I called them all up. I said, ‘I can take the plane up to 3,000 feet and you can bail out, if you wish, and you’ll be okay because that’s the safe bailing out height, and then I’m going to see if I can’t land the plane and save the skipper.’

“They all volunteered to stay with me, and so I headed for the runway. I had just set the revs flat at 15 degrees, and I was just dropping the wheels, and [with] the shaking of the plane, the skipper indicated that he wanted to get back to his seat … so I stood behind him, and sort of rode shotgun.

“He made a perfect landing, but then half way down the runway he collapsed onto the controls, and I had to stop the motors and put the brakes on to stop us.

“The ambulances came racing along the runway, and they came aboard, and lifted him out, and took him away. He was operated on by two eyes specialists and bone specialists because a piece of ‘ack-ack’ had gone straight on into his face just under the left eye. They said afterwards that another fraction of an inch and he would have been killed instantly.”

Laurie Woods, left, during the war. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

Laurie knew how close they had all come to being killed.

“We were pretty lucky we survived that,” he said. “I just stood there, thankful to be on the ground. The rear gunner said, ‘I could have done that,’ and … and the navigation leader, who was much superior in rank to what I was … turned to him and said, ‘You were a scrub pilot, and I was a scrub pilot, and neither of us could have ever flown home in weather like that.’ And that was that.”

For this “sterling display”, Laurie and the pilot were each awarded an immediate Distinguished Flying Cross.

“At no time was the Bomb-Aimer flustered and he displayed skill, initiative and determination of a high order,” the recommendation read. “The whole performance was remarkable … an outstanding example of coolness, initiative, resource and purpose … a fitting conclusion to an excellent tour.”

Laurie Woods always wanted to fly. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

Laurie, a warrant officer at the time, also received an immediate field commission as a pilot officer.

“For a couple of days, they just about drove me mad,” he said. “Everywhere I went, they said, ‘Gong, gong,’ which mean decoration, and then they organised for me to go by train to London.”

Back at his home in Tasmania, his mother knew immediately that something had been terribly wrong.

“That’s another story,” he said.

“There was a minister of religion staying with my Mum and Dad. Mum had a dream that woke her up and she thought I was in deadly danger, so she got up … and she thought she’d have a cup of tea.

“This minister came out and she told him about it, and they had this cup of tea together, and said a prayer or two. Maybe it was the prayer or two that helped me out, and it happened at exactly the time that we were hit … It’s unbelievable … and she was very happy when I came home.”

Laurie Woods was born on Boxing Day 1922. Photo: Courtesy Laurie Woods

A railway worker from Tasmania, Laurie enlisted into the Royal Australian Air Force in June 1942 at the age of 19.

“I left school at the age of 13 and I wanted to improve my education,” he said. “I tried to get my parents to sign [the papers] for me to join the navy as a cadet bandsman at the age of 16, but they wouldn’t hear of it.

“When conscription came in, I said to them I should join the air force before I get dragged into the army. They didn’t know that I was in a reserved occupation, so I didn’t play fair with them.

“When my mother found out I was in air crew, she said, ‘That’s pretty dangerous isn’t it? Can’t you get out of it?’ I said, ‘No, not really, but if I don’t pass my exams I will automatically become a cook or a guard,’ and so after that, every letter, she wrote, ‘Please fail.’”

Photos: Courtesy Laurie Woods

He completed training in Victoria and South Australia before being sent to the United Kingdom via America.

“We were in America for six weeks … and then we were loaded aboard the Queen Elizabeth,” he said. “About halfway across the Atlantic, on the third night I think it was, we were practically tipped out of our bunks. We were told afterwards that they thought we had run into a pack of subs or whales, and so they kept on full speed for 12 hours, and we got away with it.”

He remembers arriving at Greenock in Scotland, and travelling by overnight train to Brighton in the south of England.

“As we went through the various places we could see the damage that the bombing had done to England,” he said. “It was terrific; in some places, a whole block of housing was just wiped flat, and it made us a little bit hostile, and we reckoned the sooner we got to doing the same to Germany, the better.”

No. 460 Squadron was equipped with Wellingtons, above, Halifaxes (briefly) and Lancasters during the war.

He was training in Wellington bombers at Litchfield when he had his first near miss.

“We nearly came to grief there because one of the motors went wrong,” he said. “One night we were flying, and it turned us upside down at 1,000 feet. The rear gunner reported that as we started to climb we passed by the tower of the church – the cathedral at Litchfield – but it was just one of those things that happened.”

The night before D-Day, Laurie and his crew carried out two diversionary raids near the Dunkirk area in Halifax bombers to draw German fighter planes away from the beachhead.

“It was a busy time,” he said. “We were briefed at that stage for 21 raids, and we flew four of them in seven days; that’s how bad the weather was.

“On the way back we passed over either a German or a British naval ship and we collected a shell. It put a hole in the side of the plane, about two foot square.

“On a raid to Paris, [we] ran into a pack of fighters and they were firing some sort of rockets that seemed to be following us. We called them ‘Chase me Charlies,’ but the intelligence officer said, ‘There’s no such thing, you must have been dreaming or something.’ But it was actually heat-seeking missiles that these fighter planes were firing, and it was possibly the first time they had been used.

Ground crew "bombing up" a Halifax aircraft in 1944 in preparation for a raid over Germany.

“After D-Day, the British troops were down at Caen and Ferfay and we were called on to bomb the troops. So we did two raids, each on a Saturday, and we blasted these German troops out of the way, but in doing so, in the first three months following D-Day, Bomber Command lost more men than the British Army did on the ground.

“Then for the next two or three weeks we were raiding railway stations and any type of transport that could be bringing supplies in to the army.”

On the night of 30 June 1944, Laurie’s crew were among 118 Lancasters which took part in a raid over railway yards at Vierzon. The raid was successful, and the target was bombed with great accuracy, but at a cost of 14 Lancasters.

“We then had raids into the Ruhr Valley, which was known as the ‘Valley of Death’ because so many airmen had been killed there,” he said.

“Altogether we did 19 trips in the Ruhr Valley, and on about our seventh raid, a Lancaster was blown to pieces just above us, and wiped out half the pilot’s canopy.

“Before that happened, I was shaking like a leaf and couldn’t do anything; I thought, ‘How am I going to do my job?’ But after this terrific explosion, there was a rush of air and the noise of motors, and I was right. I was quite calm.”

A Lancaster bomber of No. 460 Squadron being "bombed up" at Binbrook for operations.

They had another near miss in a raid over Germany.

“Our navigator had his arm smashed over Stettin when an incendiary bomb came through the roof,” he said. “It didn’t explode, fortunately, but it smashed his arm. The only part of his watch that we found, was the watch-works itself. The case and the strap were never ever found. We don’t know what happened to it, but the wireless operator grabbed hold of this incendiary bomb, and he shot it down the open chute where the camera used to take a flash when we dropped the bombs.”

It was a nerve-wracking time for everyone.

“It became part of a day’s work, going out, but of course, you would wonder sometimes what the target was like, if it was a hot target or whatever …

“I was right in the front … particularly at night, when the shells came up, they would have a tracer about every fourth shell. You could see it, and it was always headed for my stomach. It was getting a little bit too close for comfort, but I could direct the pilot to go left 10 degrees, or go right, and dodge any of those things, and then I had to report to the navigator any explosions or any planes that were shot down … but it was pretty good, flying. It gets into your blood.

“We had a job to do and we wouldn’t let any of our crew down.”

The crew meant everything to him.

“Any one of us would have given our lives to save our crew,” he said. “They were more to us than our own flesh and blood.”

He remembers fearing the worst during one raid.

“The engineer nearly caused us to lose our parachute hatch one night,” he said.

“We had to circle until everyone had taken off and then we had to land; our safety landing weight was 56,000 pounds, and we came in with 64,800, and that became the new record for Bomber Command.

“We took off and we got to 12,000 feet and he had to switch the petrol [supply] from the main tank to the outer tank … but instead of doing that, he switched onto an empty tank. One motor started to cough … so I raced back, and I had just switched it, when the second motor started to cough.

Laurie Woods, centre, with the Minister for Veterans' Affairs Darren Chester and the Director of the Australian War Memorial, Dr Brendan Nelson.

“We started to drop to 4,000 feet … and we were late over the target. There was no sign of any guns or any searchlights or anything, and I said to the skipper, ‘Well, I can’t see anything, but I’ll leave it to right at the last minute for you to open the bomb bay, and as soon as I drop the bombs I’ll tell you, and you can dive, and dive flat out.’

“We’d just got right over the target and they started shooting at us – about 50 guns all firing away madly at us.

“The [bomb doors] had only just opened, and I let the bombs go, and then I said, ‘Dive, dive!’ Straight below, we dropped a photo flash and took a photo of the target. That was the only way we could get a photo, and if we didn’t get a photo, we were court martialled.

“We dived from around about 18 or 20,000 feet down to about 200 feet in pitch dark and they were shooting along the ground at us by the time we straightened out.”

Laurie Woods at the Memorial with Director Dr Brendan Nelson.

Today, almost 75 years after his last mission, Laurie still considers himself lucky to have made it home. It was then that he finally got to meet the newest member of his family.

“I was married before I went overseas,” he said. “I met my daughter, who was two years old, and it was the first time I’d seen her.”

He has since written books about his experiences during the war and has been active in the RAAF Association, the RSL and the 460 Squadron Association, serving as President for Queensland 460 Squadron Association since he was elected in 1990.

He was awarded the rank of Chevalier in the French Legion of Honour, which honours veterans who fought for the liberation of France, and was recognised in the 2015 Australia Day honours for his significant service to veterans through the preservation of military aviation history.

It meant the world to him to travel to the Memorial and remember his mates who were lost.

D-Day: the Australian story is on display at the Australian War Memorial in the mezzanine area of Anzac Hall until September 2019. For more information, visit here.