'By all the rules, it should have ... blown the whole lot out of the sky'

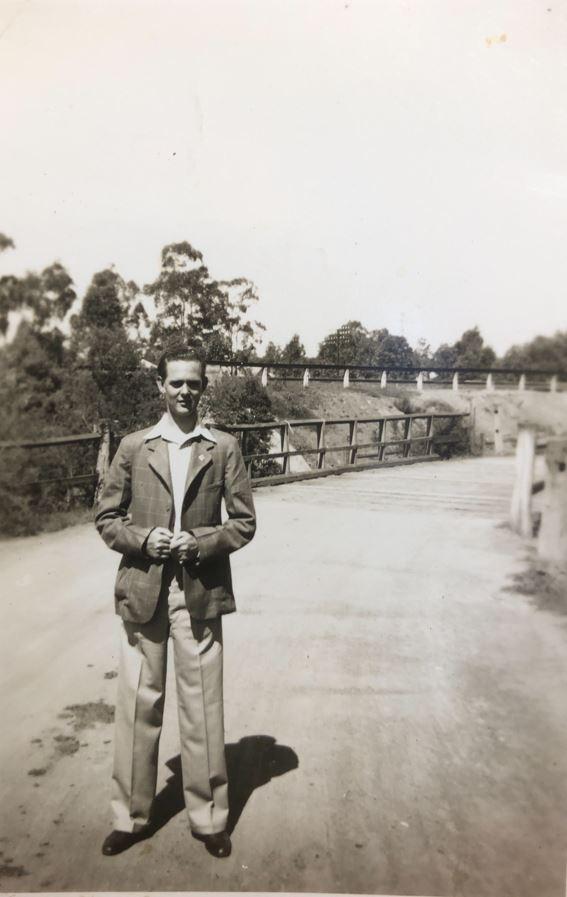

Len Davies was not yet 18 when he enlisted during the war. Photo: Courtesy the Davies family

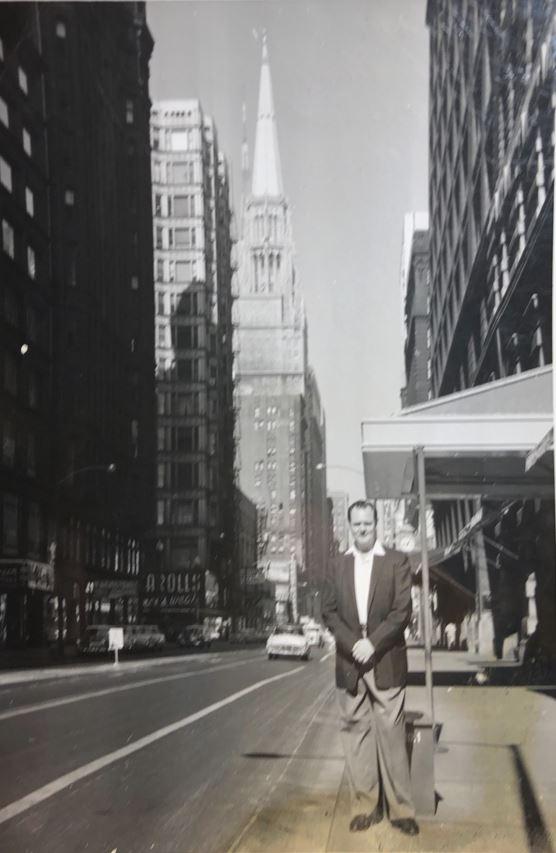

Len Davies was 19 years old when he was given the order to jump.

It was February 1945, and Len was serving as a rear gunner with Bomber Command when his Lancaster ran into trouble over Germany.

“One of the engines was crook on take-off,” he later recalled.

“It was the one that fed my turret, and I could feel it vibrating all the way. It blew up just as we got over the target, and we had to turn for home.

“By all the rules, it should have burnt through to the petrol tanks and blown the whole lot out of the sky.

“The pilot told us to bale out, and three of us did.

“Just as the pilot was going to follow, he saw the flames dying down, so he flew her home.

“When they landed, the engine just dropped off on the tarmac.

“Meanwhile, we were drifting over towards France, but the wind blew us to Germany, and I saw the war out in a prison camp.”

Len Davies, pictured right, with two of his fellow airmen. His father and brother served in the Army during the war. Photo: Courtesy the Davies family

It was a long way from where he’d grown up in Perth. As a boy before the war, Len had sold newspapers at his pitch near His Majesty’s Hotel. He dreamed of becoming a cartoonist one day, and would while away slack periods by drawing cartoons on the white-washed walls of the hotel. The publican didn’t mind. He argued it was good for business because so many people stopped to look and stayed for a drink.

When a newspaper man asked the youngster – “a fair-headed, cheerful well-knit kid … one of the city’s most popular newsboys” – if he had ever learnt drawing, the 13-year-old Len shook his head.

“No. But I wish I could,” he said. “I like drawing ... Sketching just comes natural.”

He was working behind a counter at Baird’s Department Store in Perth when he put his age up to enlist during the Second World War. His father and brother were both serving in the AIF when he joined the Royal Australian Air Force and trained as a rear gunner.

He continued cartooning in the air force, designing the nose art on his crew’s Lancaster, and sketching images “all over the walls of the Sergeants’ Mess”.

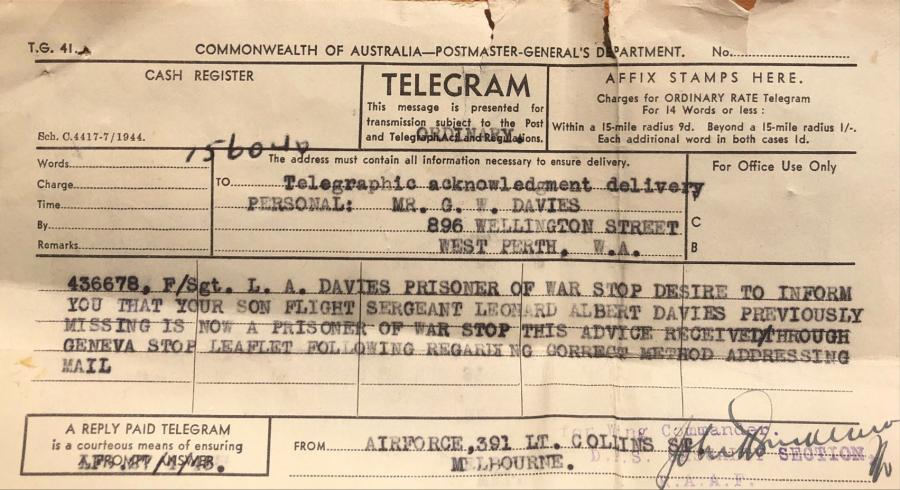

The telegram that was sent to Len's family during the war. Photo: Courtesy the Davies family

He was serving with 467 Squadron at Waddington in the United Kingdom when he was ordered to bale from his burning Lancaster during a night raid over Karlsruhe, Germany. He was captured in the Black Forest and taken prisoner by the Germans.

The war in Europe was all but over in April 1945, when the prisoners at Nuremberg, the scene of Hitler’s biggest pre-war rallies, began their forced march to Moosburg. The march, covering some 160 kilometres, was one in a series of epic Long Marches that took place during the final stages of the war.

With little or no food, Len survived on what he could.

“Men would starve [if not] for Red Cross parcels,” he wrote in his diary at the time.

“Miserably wet, tired and cold…

“Saw several Allied aircraft. Signalled to them with large POW sign [made of toilet paper and empty Red Cross tins]…

“Ringside seat of terrific bombing of Nuremberg… Artillery fire heard distinctly all day…

“Guards are becoming very [trigger happy]. One man shot in hip.”

He would later recall how American dive bombers attacked a rail bridge, killing three of the prisoners.

“The planes were US Thunderbolts,” he said. “They circled, then one plane dived.

“I saw a bomb leave the plane, and an explosion followed.

“The second plane started to dive … but the pilot, probably realising that the men below were POWs, suddenly pulled out.

“Both planes then circled once or twice then flew off.”

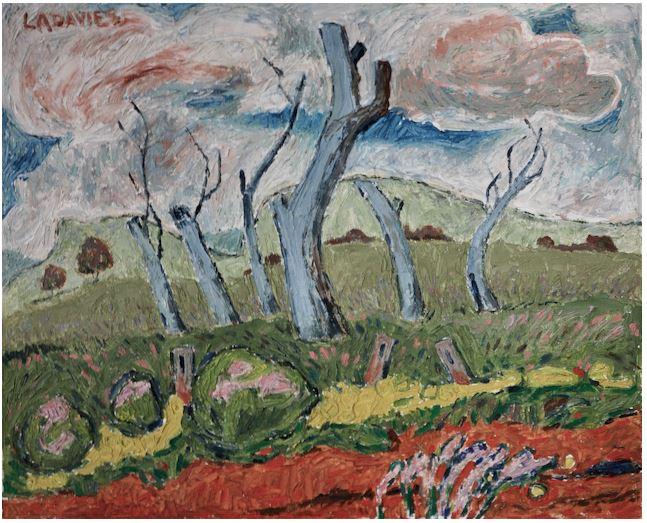

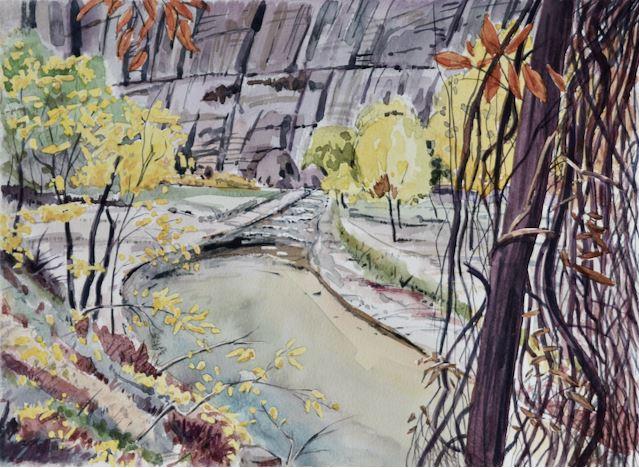

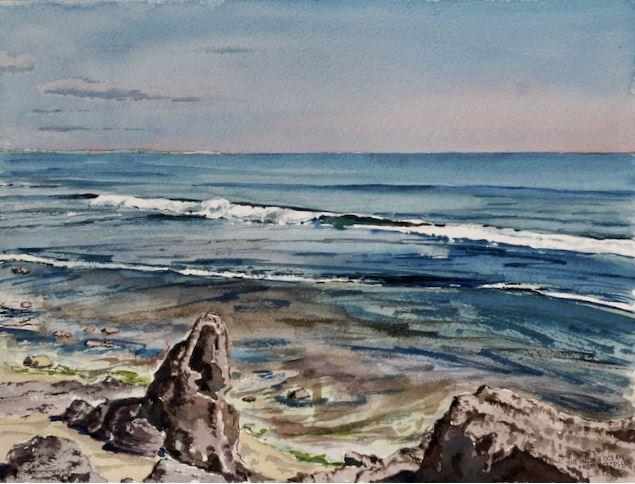

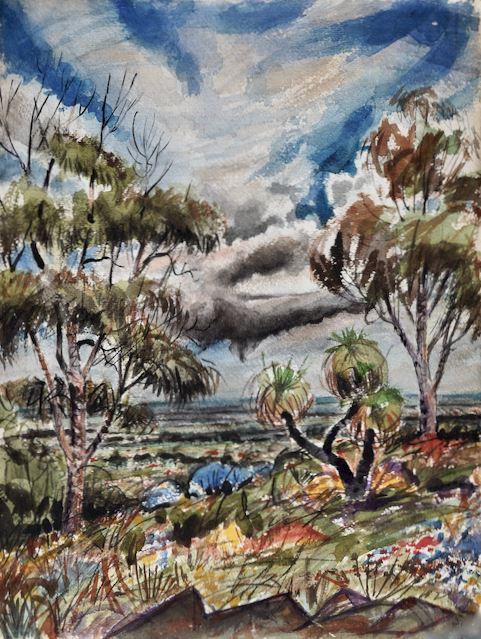

Len Davies turned to his art after the war. Images: Courtesy the Davies family

After the war, Len turned to his art.

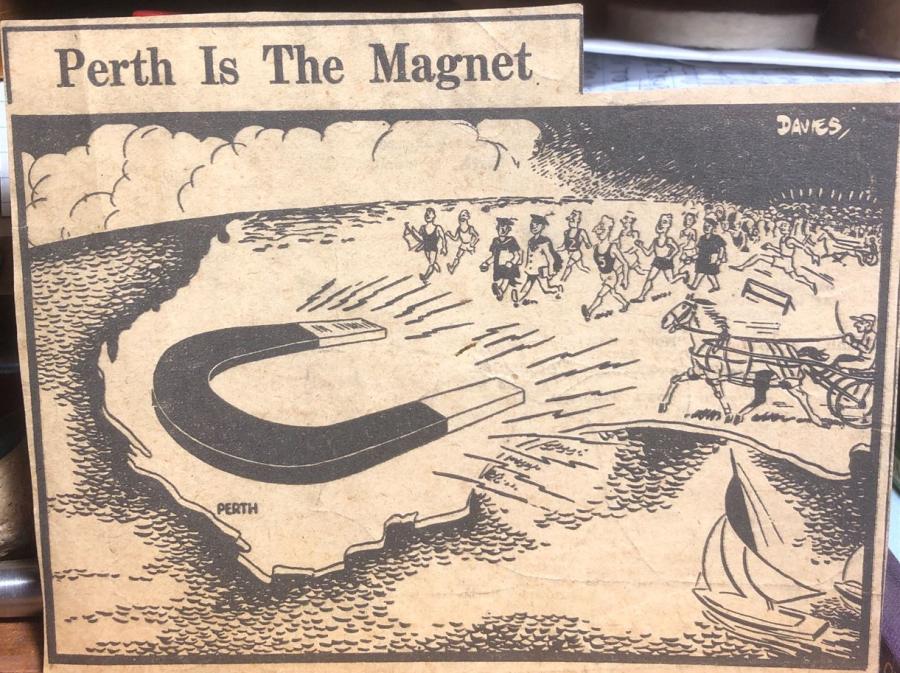

He completed a rehabilitation art course, becoming a political cartoonist for the Sunday Times in Perth, a sports cartoonist for the Daily Mirror in Sydney, and a fashion artist for Sears and Roebuck in Toronto, Canada.

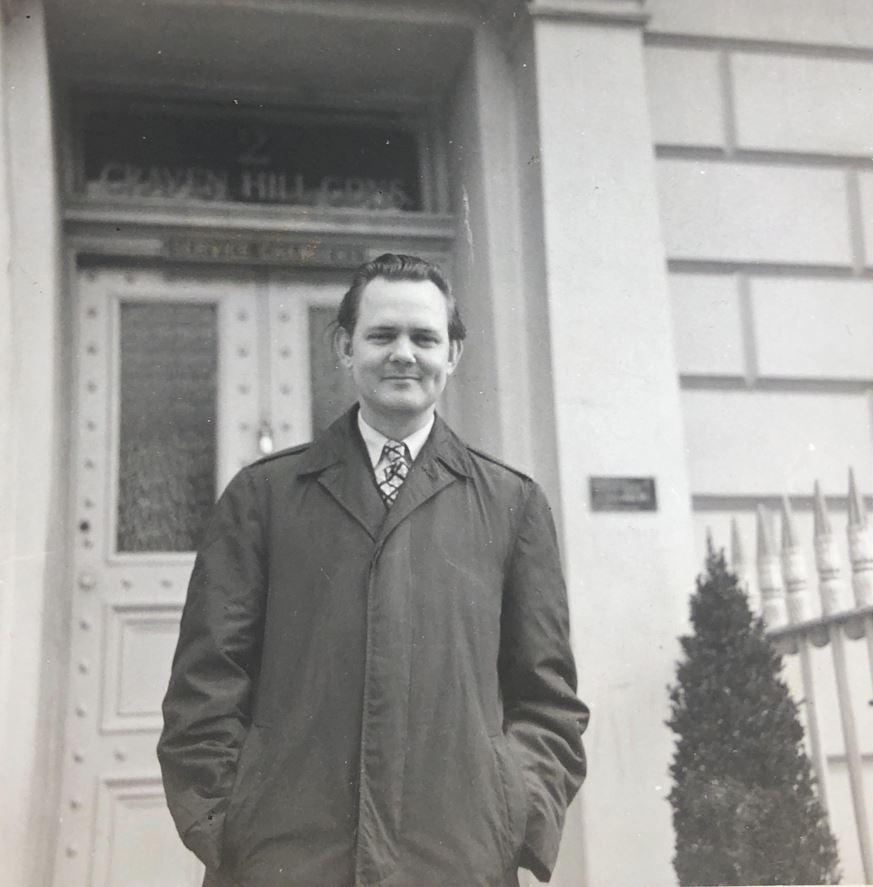

He stayed in Toronto for seven and a half years, but eventually the cold “drove him” back to England, Ireland and Scotland, where he worked as an illustrator.

“I think I must have gone through three or four pairs of ears while I was in Canada,” he told reporters. “They all dropped off in the cold.”

Len returned to Australia, and continued to paint in oils and watercolours for many years. He loved visiting the outback and could often be found painting the trees and wildflowers at King’s Park in Perth.

“I’ve got four to five hundred paintings here [in Perth] and in Melbourne,” he said at the time. “One day I’ll hold a giant exhibition … and live off the proceeds for the rest of my life.”

Len never got to hold his exhibition. He died in Perth in 1995.

Len Davies became a successful cartoonist after the war. Image: Courtesy the Davies family

His nephew, Ashley Davies, has composed an album of music inspired by his paintings and is planning an exhibition of his works to help tell his story.

“Every family has a favourite uncle or aunty, and Uncle Len was ours,” Ashley said.

“He was always at Christmas lunches and Easter lunches … and we just loved him…

“He never seemed rattled… and as a kid growing up, he was just the best. He taught us how to play draughts and chess, and he was always great to hang around with.

“He told great stories… but he never talked about the war… I didn’t even know the story of the Lancaster until he passed on.

Len Davies returned to Britain after the war. The briefing room for 467 Squadron is marked with X. To the left was the squadron headquarters. Len served with 467 and 463 Squadrons during the war. Photo: Courtesy the Davies family

“There was only one time, at Christmas, when I was a little bit older … I must have asked him what was it like.

“I can still see it clearly. He was sitting in a chair and he didn’t say anything. He just put his head down, and put head in his hands, and said, ‘You can’t imagine.’

“He was very quiet … and I just knew not to go any further … he didn’t want to go there … he didn’t want to talk about it … and I could kind of understand why.

“He was a pretty young kid when he signed up.

“You’re in this Lancaster … you’ve got the ammunition either side of you … and you’re seeing these other planes, swirling around you, ducking and diving …

“I just can’t imagine how terrible it must have been for him and what he would have gone through.”

Len Davies. Photo: Courtesy the Davies family.

Ashley’s mother Jenny was married to Len’s youngest brother, Graham. Len would sometimes speak to her about the war when she drove him home from the local pub.

“He was one of four children,” she said.

“The eldest son, George, was the tough big brother, but Len was not. He wasn’t a fighter. He was a gentle man, but he wanted to go away and do what his father and his brother were doing … so he went and put up his age to get into the air force.

“By the time he was 21, he’d been to war and he’d been through all of these horrific experiences.”

“I remember, he said to me, ‘It’s funny, there are some things that are still so strong in my memory … one night I could see they were moving around the camp. We were all in bunk beds and they came over to me and just in time I woke up … they were throttling the inmates … and I still wake up at that time each night.’

Len Davies pictured in his uniform. He carried a photograph of his childhood sweetheart in his wallet with one of her letters, which he kept for the rest of his life. Photo: Courtesy the Davies family

“One of the squadron’s mottos was ‘Press on Regardless’, and I heard him say that so many times.

“They knew when they sat in that room, getting their orders for that day, that some of them would not come home, because once the searchlight hit the plane, they knew they were marked.

“When they were given the order to bale out, it took him a while, because his leg got caught in a strap.

“He was going to get married to this girl … but when he was missing, they thought he was dead … so by the time he got back home, she had married someone else.

“She must have been the love of his life because he never married and he never had any children.”

When Len died, he left all of his paintings and drawings to Ashley’s mother. His art had helped sustain him, during and after the war.

“Art was his great love, and that’s why I’m doing [the album and the exhibition]. It’s about paying homage to Uncle Len, and telling his story.”