“An expensive and vain attempt to take a prisoner”

It was an icy winter’s eve in Korea on 24 January 1953 when 31 men from the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) gathered on Hill 355 for a snatch patrol. Led by Lieutenant Francis Smith, a 23-year-old Duntroon graduate, their objective was to capture a Chinese soldier in order to gather military intelligence.

Patrols and vicious trench raids had become the norm in Korea. Following a series of limited offensives in late 1951, the war had turned static. United Nations forces sought no further significant offensives as it was thought that the cost of victory would prove unpalatable to most contributing nations. Instead, the quiet was punctured by constant patrols, raids, wiring parties, airstrikes, and naval bombardments.

Moving carefully down the frozen slopes of Hill 355, the men of 3RAR trudged slowly towards their target: a communications trench 1,500 yards behind Chinese lines. Despite the cold, Private Lionel Terry – known as “Bomber” – was warm and clean. Terry had taken a bird bath and changed his underwear just before the patrol. “The bastards won’t find me in dirty gear”, he had said laughing.

Private Lionel Terry. This photograph was taken just after Terry’s bird bath on the afternoon of 24 January 1953 (P09413.001).

On nearing their target, the patrol formed three discrete parties. A five-man snatch party, led by Sergeant Edward Morrison and including Terry, was to enter the Chinese trenches while two groups of 13 men – under Smith and Corporal Francis Mackay – provided cover and protected the withdrawal route.

It was then that the situation descended into chaos. Two Chinese sentries challenged and fired upon Morrison as soon as he jumped into the communications trench. Morrison killed both men, but the element of surprise was lost. Concentrated rifle and machine-gun fire opened up on the Australians and Terry was wounded in the abdomen.

Morrison’s party withdrew, linked up with Mackay, and radioed for artillery and mortar support. As the shells began to rain down, a Chinese company made a coordinated attack on Smith’s position.

Morrison led his group of 18 to assist Smith, dispatching an unsuspecting Chinese patrol along the way. But it was too late; Smith’s group was overrun. The young lieutenant was hit by a concussion grenade and never seen again.

Morrison had no choice but to lead his party eastward in a fighting withdrawal. Pursued by the enemy, the Australians had a vicious fight along the ridges towards Hill 355. At one point, Morrison and Mackay rushed forward, killing six Chinese troops in brutal hand-to-hand combat.

As the Australians closed in on friendly lines, Morrison and his men were attacked on the flank by two Chinese platoons. Morrison twice rallied the men and charged forward to fend off the attacks. A third platoon made a simultaneous assault from the rear. Despite his earlier wound, Terry charged towards the rear group, firing his Owen gun and hurling grenades. Terry’s shock action dispersed the Chinese attack. The 22-year-old private, famous for his “million dollar smile”, was not seen again. But his decisive charge enabled the remainder of the party to make it back to Australian lines.

Eleven of the survivors from the snatch patrol. Sergeant Jack Morrison is front on the right

The patrol had been a disastrous failure. The snatch party had failed to capture a prisoner and the operation had cost 3RAR seven men killed or missing, six taken prisoner, and a further ten wounded. The incident had been, as official historian Robert O’Neill later wrote, “an expensive and vain attempt to take a prisoner”.

Nevertheless, the patrol was credited with having killed as many as 80 Chinese solders, and Morrison was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal, Mackay a Military Medal, and Smith was posthumously Mentioned in Despatches.

Sergeant Jack Morrison is presented with the ribbon of his Distinguished Conduct Medal by Major General Michael West, 18 March 1953

Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Hughes and Brigadier Thomas Daly considered recommending Terry for the Victoria Cross, but there was insufficient evidence and witnesses for the case to go forward. He was instead Mentioned in Despatches in 1955.

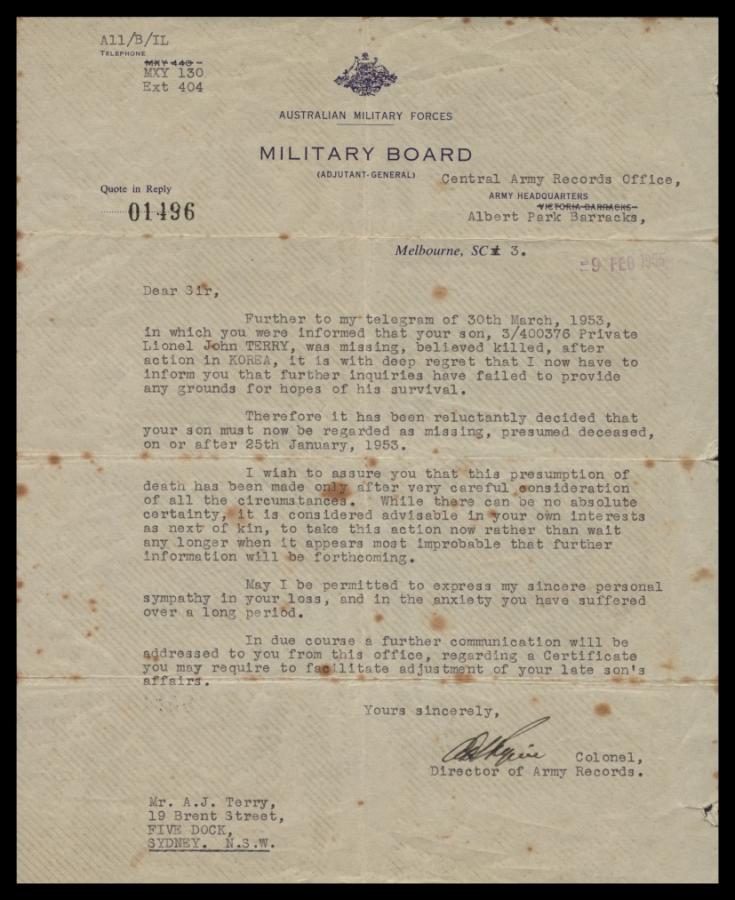

The award offered little consolation to Terry’s family. He was officially posted as missing but despite an extensive search his body was never recovered. After further inquiries failed to produce any new information, the Director of Army Records wrote to Terry’s family in February 1955. The army’s investigation has “failed to provide any grounds for hopes of his survival”, he wrote: “Therefore it has been reluctantly decided that your son must now be regarded as missing, presumed deceased.”

The letter sent by the Director of Army Records to the Terry family, 9 February 1955 (PR04757).

Arthur Terry spent the remainder of his life living in hope that his son would return home. Terry’s loss also dealt a severe blow to his younger sister, Louise, who made numerous inquiries to find out what exactly had happened to her brother in the 1990s. Louise’s correspondence with her brother’s former comrades and mates is held by the Research Centre in PR04757. The collection tells the story of a well-liked and colourful character, whose loss was keenly felt.

Sandwiched between the Second World War and Vietnam, the Korean War is often overlooked. But the snatch patrol of 24/25 January 1953 highlights the vicious fighting that occurred during the three-year conflict, and how the war had echoes beyond the heat of battle. Lionel Terry was just one of 340 Australians who died while fighting as part of United Nations forces on the Korean peninsula, 43 of whom remain missing.