The Man Behind The Bearskin

Concealed beneath the fine jet black hairs of this bearskin headdress is the gilded flaming grenade badge of the Royal Fusiliers. The bearskin headdress worn with the traditional scarlet full dress uniform during ceremonial and state occasions by British soldiers is an impressive sight, emblematic of the sartorial military splendour of the 18th and 19th century.

The British tradition of wearing bearskin headdresses began a century before the First World War, when it was adopted as a symbol of victory after the Battle of Waterloo. On 18th June 1815, the British 1st Regiment of Foot Guards (later the Grenadier Guards) was given the right to wear the bearskin headdress of the defeated French grenadiers of Napoleon’s elite Imperial Guard. Soon this symbolic right was extended to the full five regiments of Foot Guards, and remains their privilege today.

This particular bearskin headdress, however, was worn by an Australian: Captain Frederick Wilberforce Alexander Steele who served with Royal Fusiliers, from 1910 to 1914.

Born in 1885, Steele was the eldest of four boys born to Philip and Johanna Steele. Raised in Melbourne and educated at Melbourne Grammar School, at the age of 20 he was commissioned a second lieutenant with the Australian Field Artillery in 1905. Eager for active service abroad, two years later Steele transferred to the British Army’s reserve 2nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers.

Steele was one of thousands of Australians who served with the armed forces of allied nations in the First World War, often long before Australians fought under their own flag at Gallipoli in April 1915. In particular, many Australians travelled to Britain to enlist at the outbreak of war, some out of a sense of adventure, others because of strong political convictions or familial connections between Australia and Britain.

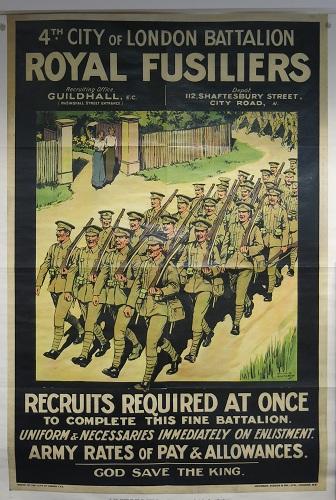

For Frederick Steele, a career with the British Army offered all the opportunities for full time military service that were unavailable with Australia’s domestic militia. In April 1914, after ten months stationed in Calcutta with the 2nd Battalion Royal Fusiliers, Steele transferred to the regular 4th Battalion, City of London Regiment, Royal Fusiliers. Despite his fears that the war would be over before he could do his bit, his transfer came in time for him to experience the active service and the adventure he had craved as a young man.

The 4th Battalion, which formed part of the 3rd Division of the British Army, had mobilised remarkably quickly and embarked for Havre within days of the British declaration of war. Steele and his battalion travelled by train across France to Landrecies where they disembarked and marched toward Mons to meet the First German Army.

The first major contact of the British and German armies took place at Mons on 23rd August 1914, and is often remembered for the British retreat which followed. The British infantry at Mons were attempting to halt the German advance through Belgium and form a line of resistance on the Mons-Conde Canal, for which Steele and his battalion would prove integral.

Here, Lieutenant Steele witnessed many acts of bravery during the battle and retreat at Nimy, two of which left such an indelible impression that he recommended the men involved, Lieutenant Dease and Private Godley. Dease had repeatedly left his trench on patrol to inspect the bridge defences and was severely wounded each time. The last patrol cost him his life for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously. Godley had volunteered to man the last machine gun as the Fusiliers retreated. Thought dead at the time Steele wrote his recommendation, he was praised for ‘Coolness and gallantry in fighting his machine gun under a hot fire for two hours after he had been wounded at Mons on 23rd August’. However Godley who had been taken prisoner was notified of his award in a German camp.

Steele is among the first officers to make recommendations for the Victoria Cross in the war. A total of five Victoria Crosses were recommended that day: two by Steele.

Soon after Steele was promoted to captain and took command of a company. Writing home after the retreat from Mons, Steele remained positive about his experience and his future in the conflict:

“I am very fit and happy and enjoying myself. I fancy I must have been lucky. I just managed my exchange in time for this. I have looked forward to active service for so long. At present I am in command of a company and two machine guns that have done well. I was personally complimented by Sir John French.”

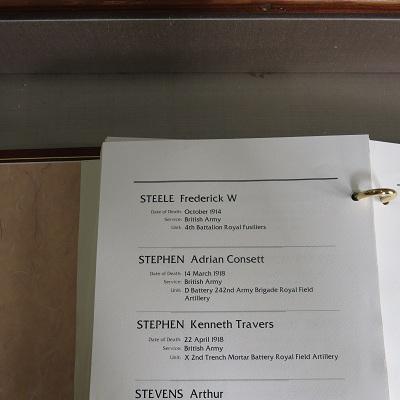

It was not long after his family received this cheerful correspondence that Steele was killed in action on October 26 at Neuve Chapelle.

Compounding the loss endured by the Steele family after the painful news of Frederick’s death was the death of two of his younger brothers; Lieutenant Philip John Rupert Steele of 4th Brigade, Australian Field Artillery, who died of wounds in the British Red Cross Hospital in Rouen on 8 January 1917, and Second Lieutenant Norman Leslie Steele of 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, who died of wounds as a prisoner of war after his Martinsyde aircraft was shot down during a bombing raid over Hareira, Palestine. The sole surviving son, Corporal Henry Cyril Augustus was promptly recalled home to Australia to be with his family and assist his father in running the family business, Steele & Company.

To commemorate the loss of the three Steele brothers locally, an oval was constructed at Melbourne Grammar School and dedicated as the Steele Memorial Ground on Armistice Day, 1928, by their mother Johanna and the surviving son, Henry. Melbourne Grammar held a special place with the family where all four brothers had each made their mark. The oval remains a testament to one family’s sacrifice. The names of Philip and Norman Steele are also enshrined in bronze on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial.

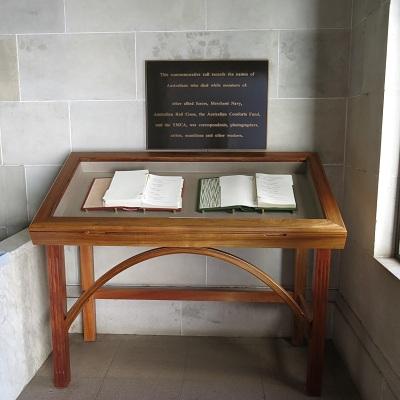

Frederick Steele is recorded in the Commemorative Roll along with the names of thousands of Australians who served with allied nations and were killed on active duty during the First World War. Intimately tied to Australia, the names in the Commemorative Roll remind us of those Australians who paid the ultimate price and whose families equally mourned their loss in foreign and distant lands.

Steele’s bearskin headdress, like much military pomp and ceremony of the pre-war period, was put aside the day war was declared and posted home to his family after his death. This bearskin headdress is one of a collection of uniforms donated to the Memorial in 1946.