'It was pretty eye opening'

Matthew Robinson was 18 years old when he climbed off a Hercules aircraft in East Timor.

“I saw my first dead body, in a gutter,” he said.

“As an 18-year-old it was pretty eye opening. It was my first time overseas, with the big boys, with real bullets, thinking that at any stage you could get into a contact. I knew it was dangerous, but at the end of the day you are doing what you are trained to do, and all that’s in the back of your mind is that if anything happens, you’ve just got to get in there, and help your mates out.”

He had been in the army for just 12 months when he deployed to East Timor in September 1999 as part of the International Force for East Timor (Interfet). It would be the first of his three deployments to East Timor.

“After the first couple of days, we punched out into the largest air mobile operation since Vietnam,” Matthew said. “We literally thought we were going into a full-blown confrontation with Indonesia, but as an 18-year-old I was thinking, I’ve just got to do my job; it doesn’t matter what happens, as long as I do my job, the guys are going to come out of it okay.

“In the back of my mind, I accepted the fact that I could become a casualty; I just didn’t want to be in a position where I could cause casualties among our own forces… and that was what stuck in my head.”

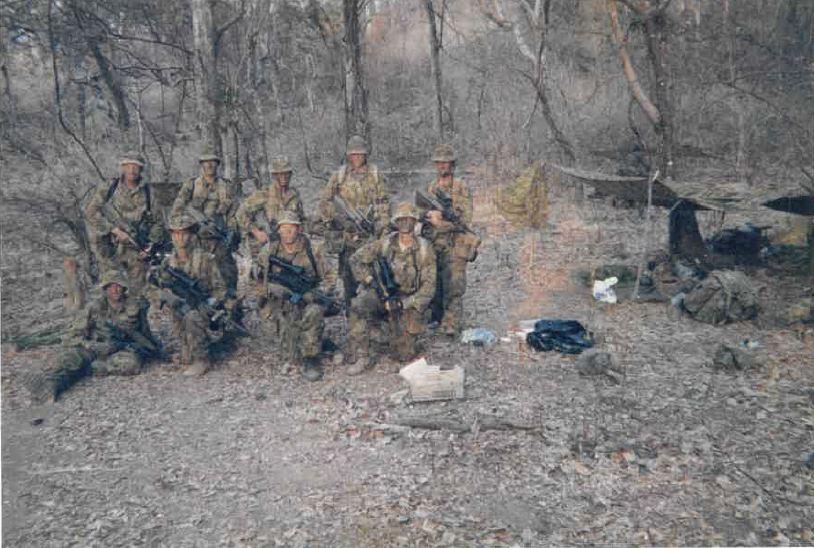

Matthew Robinson in East Timor. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

Matthew Robinson, far left, in East Timor. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

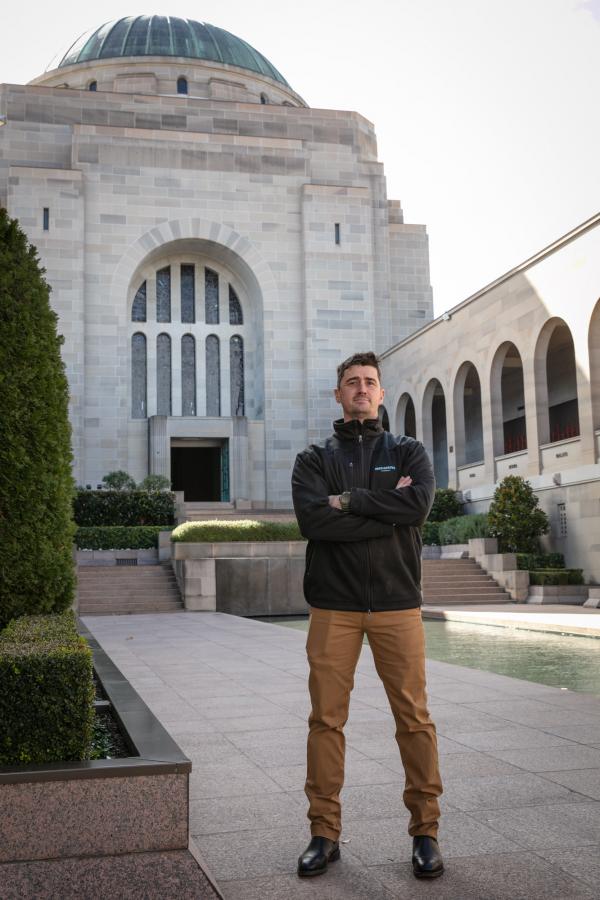

Today, Matthew is a supervisor with commercial plumbing company O’Neil and Brown in Canberra. He is proud to be one of the veterans working on the Australian War Memorial’s Development Project to help tell the stories of modern conflicts and peacekeeping operations.

It is a project that is close to his heart. He comes from a long line of servicemen and servicewomen, and grew up in a military family. His parents served in the Royal Australian Air Force, and two of his uncles served in the army; one was killed in a parachute accident. His paternal grandfather was also in the army, and his maternal great-grandfather served on Gallipoli during the First World War.

“My great-grandmother used to give me a gold coin and tell me stories … and I knew from a very young age that I was going to join the army,” he said.

“I grew up in Hervey Bay and right across the road from our house was bushland … so I was always in the bush – building shelters, trying to look for animals, and just having fun.”

Matthew Robinson in 1999. "I knew from a very young age that I was going to join the army." Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

Inspired by his love of the bush, and his family’s military history, he joined the army cadets at school and then enlisted in the army in 1998 at the age of 17.

“I felt drawn to the army, and at that point in my life I knew I wasn’t going to go to university or get a trade; I just wanted to be in the bush.

“I still remember to this day my Year 2 teacher, Mrs Lawson. Her grandfather served in World War II and her father was in Korea. She was a massive Australian history buff. I took all that on at school and basically steeled myself to joining the army.

“I applied halfway through Year 12, thinking it was going to take a very long time to get through, but I got a letter in July saying I’d been accepted, and that my Kapooka date was the 4th of August.

“I had to make a decision then and there: am I going to decline and finish year 12, or am I going to do it? I realised that at that time there were only three ways out of Hervey Bay – jail, university or the military – so I chose the military, and I have never regretted it.”

He still remembers arriving for basic training at Kapooka. He was a small skinny teenager who had fudged his weight to get into the army.

Matthew Robinson first deployed to East Timor in September 1999 as part of the International Force for East Timor (INTERFET). Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson.

Matthew returned to East Timor in 2001 and 2006. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

“It was pretty scary,” he said. “You had to be a certain weight, and it was lucky for me that the set of scales was right below a towel rack. When I jumped on and I saw the weight, I knew that I wasn’t going to make it, so I put my hands behind my back and lifted up on the towel rack, and managed to get one kilo over minimum weight.

“The doctor said, ‘Yep, too easy,’ and that stuck in my brain when I got to Kapooka getting screamed at. I’m only a small guy, and I’m thinking, ‘How am I going to be able to do this?’

“It’s very intimidating, especially at 17. It’s pretty intense… but when I came home on my first lot of leave, it made me realise that the choice I had made 12 months before was the right one.

“I struggled through Kapooka, and I struggled through infantry training school at Singleton, but I managed to go through, and I was so happy.

“When a person leaves Kapooka, they are a soldier who can be moulded into a war fighter or a vehicle mechanic or a helicopter engineer. Kapooka is Kapooka, and it gives me hope and a bit of pride to say every soldier is the same when they get out of that place. I would hate to think where my life would be if I hadn’t joined the army.”

He was injured during his final assessment at the infantry training school in Singleton, but was determined to continue on.

“I broke my foot in the first kilometre, and it was a 15 to 18 kilometre run,” he said. “I just kept going, so by the end of it all, I couldn’t even feel my foot. We had to cut the laces to get the boot off, and it was just purple. It had to be set so I couldn’t pass out with my mates, but I still passed, and that’s all I cared about – I’ve done it, I’ve passed it, and I’m out.”

Matthew Robinson, far right. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

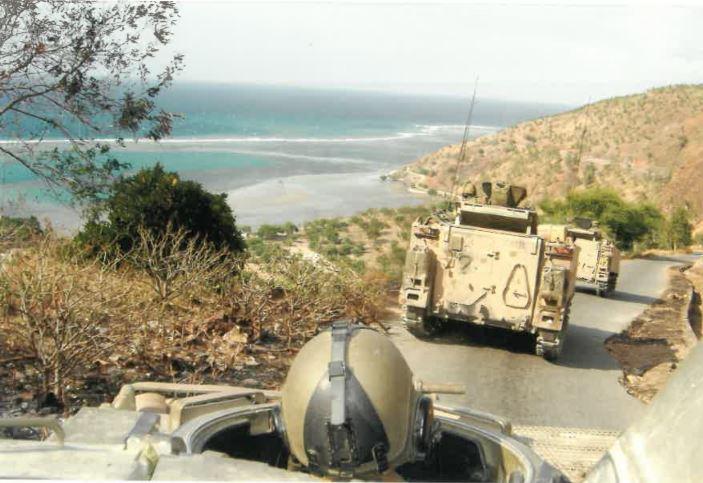

Making their way along the coast. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

He was posted to the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, in 1999 and was sent on his first deployment in September.

“When we first heard about going to Timor, we didn’t really think that much of it,” he said. “I had just turned 18 – 18 and three months – and we found out we had eight hours to move. I’d bet that we weren’t going to go – so I lost that bet – and eight hours later I was on a Hercules going to Dili. I was right at the back of the Herc, and I had this massive pack. The pack weighed as much as I did, and so for the whole flight I was trying to prop myself up on the seat. By the time we landed, my back was wrecked, and I was so tired from trying to stay upright.”

Matthew’s unit was one of the first to be deployed once the airfield at Dili had been secured by members of the Special Air Service Regiment. He was part of the multinational peacekeeping taskforce mandated by the United Nations to address the humanitarian and security crisis that took place in East Timor from 1999 to 2000. Their role was to restore law and order and end the widespread violence and destruction that had broken out following the August referendum that showed overwhelming support for independence from Indonesia.

“I was in the second Herc in, and we piled out of that Herc thinking we were going to get shot up as soon as we got out, but the doors opened, and we didn’t cop any rounds,” he said.

“The SASR piled into their long-range patrol vehicles, and took off straight for Dili, and all you could hear were gunshots in the distance.

“I was given a machine-gun, which is odd because I was the smallest guy there, and then we started patrolling into Dili itself.

“Our company, Bravo Company, then travelled from Dili to Batugade on the coast in the back of a bucket – an armoured personnel carrier – along a windy coast road, straight to this old Portuguese castle which still had cannons.”

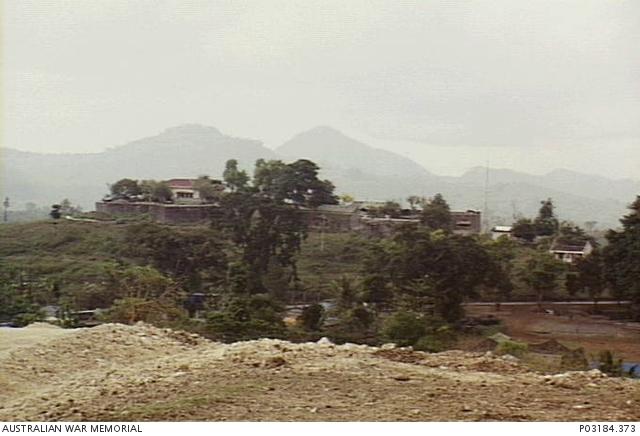

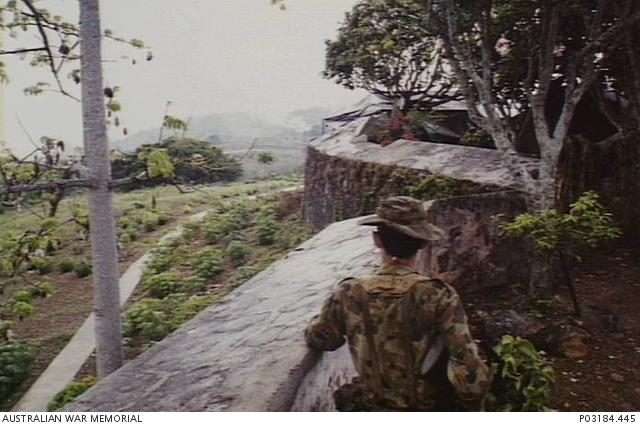

Balibo, East Timor. November 1999. A view of a Portuguese fort used as the headquarters for the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR).

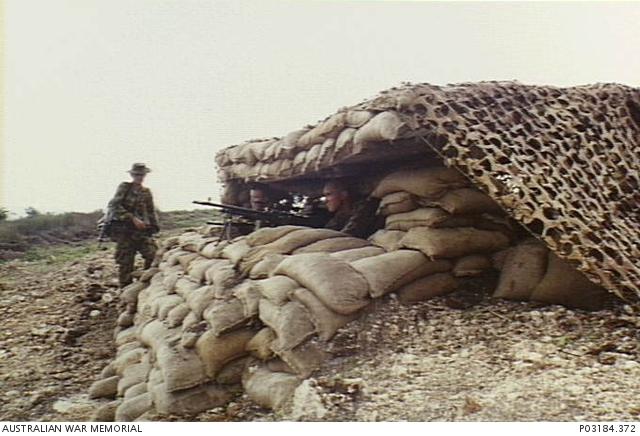

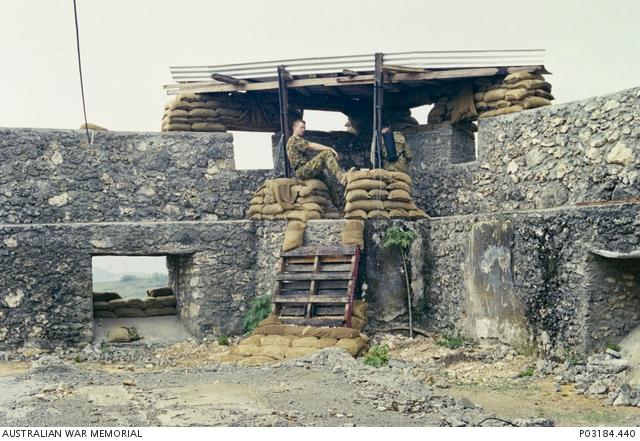

Balibo, East Timor. November 1999. The old Portuguese fort on a hill overlooking the village of Balibo. A sandbagged defensive position has been constructed against the wall of the fort and also on the top of the parapet.

Balibo, East Timor. November 1999. A sandbagged and camouflaged bunker.

He remembers patrolling in the area, and learning about the history of East Timor.

“We secured Batugade, and then we pushed up into the hills closer to Balibo,” he said. “Getting four hours sleep was a bonus, and that’s when Charlie Company decided to push up to make sure the Indonesians knew we knew where the border was. We were on overwatch on a hill and could hear everything, and we were keen to get in there and help.

“That was all in the first month, and then we punched up to Balibo and learnt about the history of the Balibo Five. I never knew anything about it till then, but we saw the house where the Australian journalists were killed, and so that was then on a lot of guys’ minds…

“It was a massive history lesson for me. We learnt all about the invasion in 1975, the massacre in Balibo, and the history of Australian service in East Timor during World War Two.

“All these ancient blokes were coming out of the hills, telling us about Australian soldiers, and Sparrow Force, and East Timor itself. It really helped us, and we got to help these guys out.

“Being 18 at the time, it was massive… We just patrolled, day in, day out, until we got the word to go. You put in the hard yards, and you’re absolutely wrecked. But I have fantastic memories.

“I had a 20-year reunion, and people were focusing on all the hard times, but I couldn’t remember them, all I could think of was the funny things… insignificant little things, but you remember them more than patrolling for 12 hours a day. I’m very happy that I got to do what I did.”

Five riflemen from 3RAR, on patrol in Dili, take shelter behind a wall as they search for members of the pro-Indonesian militia.

Balibo, East Timor. November 1999. Looking toward the hills from the old Portuguese fort being used as the Headquarters for the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR).

Balibo, East Timor. November 1999. Lieutenant Colonel Slater (sitting left), Commanding Officer of the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR), being interviewed. They are sitting on a pile of sandbags on the rampart, behind a sandbagged defensive position built on the parapet in the old Portuguese fort being used as the Headquarters for 2RAR. The old cannon port to the left has also been reinforced with sandbags.

He returned to East Timor again in 2001 as part of UNTAET, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor, and again in 2006, as part of Operation Astute following unrest between elements of the Timor Leste Defence Force. He left the army in 2008 and worked in mining before joining the Air Force and being posted to the Federation Guard. He left the Air Force to complete a plumbing apprenticeship with O’Neill and Brown, and joined the Army Reserves in 2016.

“I got half way through the apprenticeship and the army just called,” he said.

“I’m an infantryman… and at the end of the day, I was in the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. I’m an infantryman through and through… and I’m extremely passionate about it. The infantry is different to the Air Force and all the other corps. They’ve got an attitude, and even in the barracks at Townsville, you could just pick who came from 1, 2 or 3RAR because of their gait, their walk, the way they wore their hats. You can spot them a mile away. They do their job really well, and there’s just this attitude that you don’t get elsewhere. That’s what I’m really proud of… and it made me realise I’ve still got the drive, but it’s green, not blue.”

East Timor. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

East Timor. Photo: Courtesy Matthew Robinson

He is proud to be one of the veterans working on the Memorial’s Development project.

“This is my dream job,” he said. “When I first drove to Canberra from Townsville, I drove past the War Memorial, and it was the first time I’d ever been. I stopped out the front at about eight o’clock at night, and I was like, wow, that’s the War Memorial. At the time, I didn’t know anyone on the wall, but it’s my heritage, and everything I’ve ever done in my life is represented by this.

“I spent two days here, just walking around, and going through all my deployments, seeing guys that I knew plastered all over it. After all the deployments, and the guys who lost their lives in Iraq and Afghanistan, you start to see boys’ names on those walls, and it’s a bit of a reality check. You knew those dudes. You worked with them. You had beers with them. You put them through training. And it’s just this massive thing for me to be a part of that history, and now as a plumber on the Development Project. It’s part of history as well, and to be able to come here and be a part of it is massive.”

For Matthew, it’s important to tell the stories of modern conflicts and peacekeeping operations.

“There’s so much history and so many stories that could be told, let alone mine; I’m just a very small cog in a medium wheel that’s part of a bigger cog which is the army,” he said.

“It means so much to so many people. It’s everything we are, as soldiers, airmen and sailors. It’s our history … and for me, it’s my way of contributing to society … I want to make sure we do the right thing by everyone on that wall…

“It’s not just a job; I would do it even if I wasn’t paid, because it’s the War Memorial… I couldn’t have asked for a better project to be put on as a veteran.”

His daughter Grace was 18 months old when she pointed to a statue of a soldier at the Memorial and said, ‘Dad.’

“She wasn’t even born when I went through the army … just to have her point at the soldier and say, ‘Dad,’ that’s why I’m here. It really hit me. This is our place, so we can remember each and every person who has fallen, and everyone who has served.”

The Australian War Memorial’s Development Project will be sharing the stories of a new generation of Australian men and women who have served our nation in recent conflicts, and on peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. To share your story email: development@awm.gov.au

To stay informed about the Development Project sign up to the Our Next Chapter e-newsletter www.awm.gov.au/ourcontinuingstory/stayinformed