'Memories of war ... remain with you for the rest of your life'

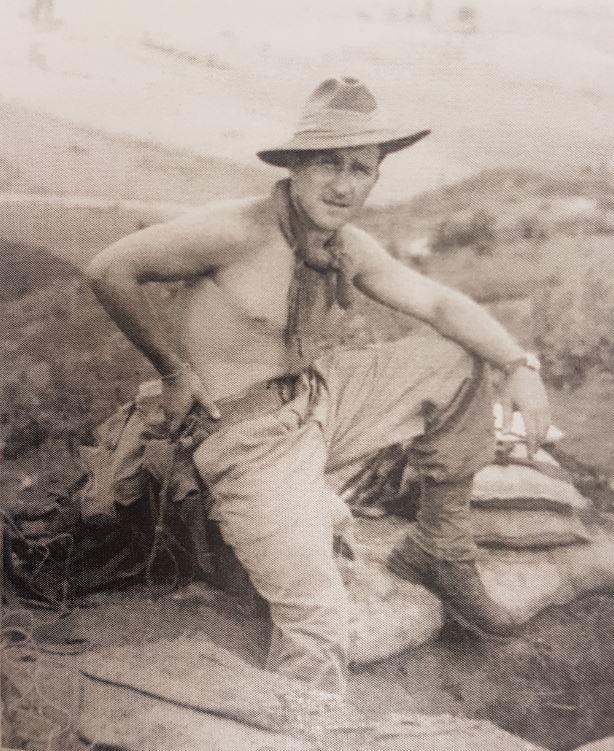

Maurie Pears pictured in Korea. Photo: Courtesy Maurie Pears

When Maurie Pears was wounded during the battle of Maryang San, he was determined to fight on with the rest of his men.

The then 21-year-old lieutenant had lost an entire section of his platoon and was wounded by shrapnel, but pressed on, capturing two hills, including Maryang San, in the space of 24 hours.

The battle of Maryang San was later described by Official historian Robert O’Neill as “probably the greatest single feat of the Australian Army during the Korean War”.

“The battle conditions up there were very hard indeed,” Maurie said.

“The enemy was strong, and very, very capable, and we were given a task behind enemy lines – one which got us into a lot of awkward situations, and one which really tested the efficiency of the Australian soldier.”

Maurie was awarded the Military Cross for his actions at Maryang San in October 1951 and for the raid on another feature, Point 227, a few months later in January 1952.

“It is an ugly business; no doubt about that,” he said. “War is difficult.

“No one can ever completely prepare you for combat action, and taking command of your first platoon. There are so many things that happen when you interact with a group of 30 men under the fear of death that no one can tell you about.

“That’s something you’ve got to experience … but like all soldiers, we adapted, and managed to perform our duty.

“I was happy to get back home in one piece.”

Hiro, Japan, October 1952: Group portrait taken after the Reinforcement Holding Unit (RHS) investiture parade. Pictured, left to right: 2/35018 Lieutenant (Lt) James David Stewart MC, of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR); 1/934 Corporal Ronald James Reid MID of 3RAR; VX700033 Chaplain Elzear Basil Phillips MBE, and of Headquarters 34th Infantry Brigade; 7/70 Sergeant Douglas Phillip Waters 3RAR; 2/35017 Lt Maurice Bertram Pears MC of 3RAR, and Captain Whalley MBE.

Maurice Betram Pears was born in Paddington, Sydney, in November 1929 and was named after the French actor Maurice Chevalier.

An only child, he grew up in a working-class family during the Depression years, and was lucky enough to be selected to attend the prestigious Sydney Boys High School. His father Bertie, a tram conductor, died soon after, leaving the 12-year-old Maurie and his young mother, Sadie, to fend for themselves.

“We survived, with difficulty, the same as so many others did, and we got through it,” he said.

“I was fortunate enough to get into [the Royal Military College] Duntroon and that was a major stepping stone in my life … If I hadn't graduated from there, who knows what would have happened.”

Maurie graduated in December 1950 and was posted to 3RAR in Korea six months later, taking command of 7 Platoon, C Company.

“I didn’t know the first thing about the country,” he said. “Our departure from Australia was a fairly secretive affair, and we were hustled out to the airfield under tight security; no one knew much about it, or where we were going, including the families.”

He will never forget arriving in Seoul for the first time.

“It was a wrecked city,” he said. “It had been severely bombed and shelled, and there were more demolished buildings there than there were new ones. It had been badly tossed about and was completely devastated.

“I was pointed in the direction of a hill and there were a group of men there who became my platoon.

“I was very young, and had a few younger soldiers with me, but most were older, and had some war experience … which certainly helped as we tried to develop into a team which would be efficient against an enemy which was quite strong and capable of putting up a bold front.”

Group portrait of officers who attended Colonel Frank Hassett's 34th birthday party. Back row: Captain Lee Greville, (3RAR); Major Bill Finlayson; Captain Peter Francis, Royal Engineers; Lieutenant Colonel Hassett DSO OBE (4th left); Major Jeffrey J. (Jim) Shelton; Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, 16th Field Regiment, Royal New Zealand Army; Major David Thomson; Arthur Roxburgh (part obscured, at rear); Major B. Hardiman (holding beer stein); Lieutenant Peter Scott (far rear); Major Nichols (holding beer stein); John P. White (far rear); Regimental Sergeant Major Hart; Captain Tom Gibson (far right, at rear); Major H. Hind; Captain B. Crosby. Front row (all kneeling): Captain W. Reg Whalley; Lt R. Fred Gardiner; Lt Maurie B. Pears; Lt Roy Pugh, and Lt Angus Waring, 5 Enniskillen (Inniskilling) Dragoon Guards.

It was a steep learning curve for the young lieutenant.

He remembers having to explain why the steel helmets they were issued with were at the bottom of the river. The more experienced soldiers had argued the helmets were too hot, and too heavy, and that they would make a noise, and allow the enemy to see them. When they declared that they were going to throw them all in to the river, Maurie thought he had better do the same. His superiors didn’t take the news too well.

On another occasion, Maurie and his platoon were selected to perform a mock attack for a film crew.

“The New Zealand publicity and army unit arrived and wanted a film to boost the morale of people at home,” he said. “But unfortunately during the firing of some of the weapons, I located a two-inch mortar in the wrong position. When it exploded, it wounded me and a few others. They were just minor wounds, but it also wounded our pride and the crew retreated fairly quickly after that.

“I doubt if the film was ever finished, and it was a very embarrassing situation for me to have to explain to the commanding officer, but we lived through it.”

Another time, Maurie and his men became dangerously dehydrated while out on a patrol across the Imjin River.

“That was probably one of the most terrifying incidents of the war for me,” he said.

“I’d never before quite realised what it’s like to be short of water … but it was my own fault. We’d gone on a patrol across the river and I hadn’t carried enough water with me to last the day.

“I was tempted of course to drink the river water … and unfortunately, I sucked in a mouthful or so of it … which made me a little bit ill afterwards because the river was full of war refuse and dead.

“It was the first time I’d understood the urgent requirement for water – it was just my fault; I didn’t carry enough water – and it was a heavy lesson which we learnt.”

In October 1951, Maurie and his men took part in the battle of Maryang San, or Operation Commmando. It was Maurie’s first major battle, and would test him to his limits.

He remembers Australia’s “Queen of Song”, Gladys Moncrieff, visiting the lines and performing for the troops before it began.

"It was a magic night, deadly quiet and calm,” he later recalled. “You could hear a pin drop as she sang in the open with a piano accompaniment; it was almost like Mum saying, ‘Look after yourself.’”

The operation, designed to push Chinese forces north and seize a series of steep hills overlooking the Imjin River, began on the 3rd of October with a British assault on Hill 355, known as Kowang San or Little Gibraltar.

The following morning, Maurie and his men led a C Company attack to help the British battalion, which had been held up. They overran two Chinese outposts in quick succession, but lost an entire section of men when they were wounded by Chinese mortar fire. Despite being wounded by shrapnel, Maurie pressed on with what remained of his platoon and took the north-eastern end of Kowang San, while the British battalion captured the south-west peak.

“It was a bitter battle because the enemy were anxious not to lose these features, which commanded a view of the whole area,” Maurie said.

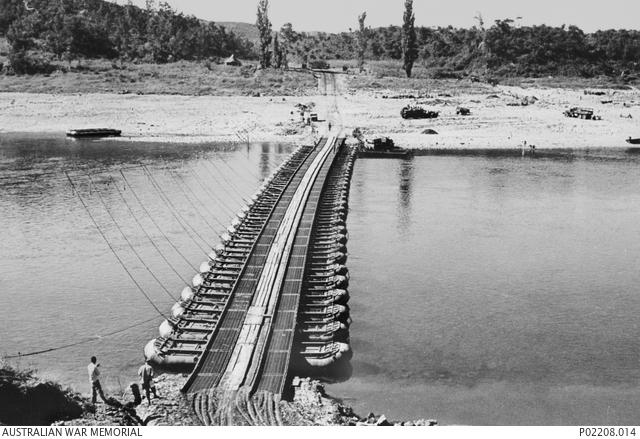

“We had to start off in the evening under the cover of darkness, cross a large river with the aid of military punts, and move up to designated forming-up areas to pursue what was a rather bold tactical plan to capture these hills.

“The approach I had to make was to an unknown objective in an unknown area in the middle of no man’s land, through numerous obstacles – and I had to ensure I got to the right place at the right time.

“I was very nervous, and not sure of my own ability to command such a good group of Australian soldiers, but we managed to find our way there through the darkness, and through the mist, and across all the rice paddies.

“The climb up the base of the hill was difficult … through dug-up gullies and ridgelines, and we came under heavy enemy fire as soon as we started off.

“We suffered many casualties – we lost 11 out of 22 men in my platoon alone during that operation – and casualties in other rifle companies were much the same.”

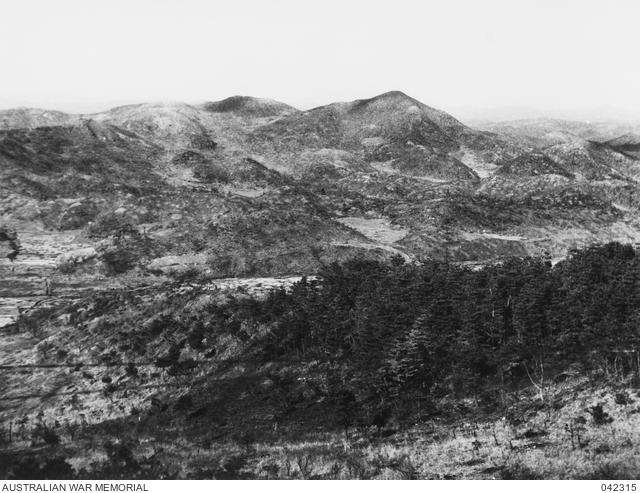

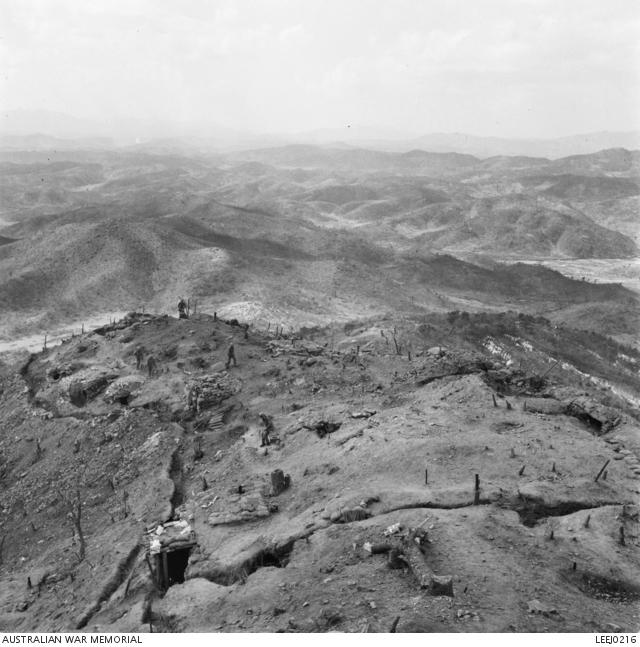

View of Hill 355 or 'Little Gibraltar' taken from Hill 210 looking north.

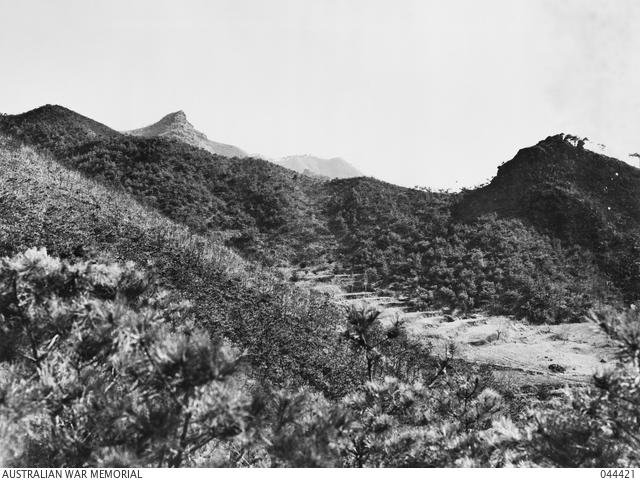

View from a forward platoon position on the northern side of Hill 355. Hill 317 (Maryang San) is the highest pyramid shaped hill to the right of the picture.

Hill 317 (Maryang San) captured by 3RAR during Operation Commando.

The following morning, in the early hours of the 5th, Maurie and what remained of his platoon took part in the 3RAR attack on Hill 317, Maryang San.

Maurie and his men led the final assault up a hill so steep that they were forced to crawl in places to finally reach summit. By the time the peak fell to the Australians, Maurie and his men had captured two hills within 24 hours.

“It was a difficult and perilous position,” Maurie said. “We were suffering heavy artillery attacks, the most concentrated artillery attack of the war … and it was just constant bombardment. It just lit the sky up. How we didn’t get more casualties is just beyond me.”

The fight for the strategically important Hill 317 was later described as “one of the most impressive victories achieved by any Australian battalion”.

Weeks later, after the Australians were withdrawn and British troops had taken over, Maryang San was recaptured by the Chinese. It would remain in the Chinese hands for the rest of the war. Of the Australians who had served in the battle of Maryang San, 20 died, and 104 were wounded.

View of hills in Korea. The nearest hill, possibly Hill 317, is occupied by troops, possibly A Company of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australioan Regiment (3RAR), who have cut trenches and dugouts into it.

“It was a harsh period,” Maurie said. “But the whole war in Korea was very harsh.

“On a number of occasions I was very close indeed to being one our own casualties and being killed in action, but that was something that the rest of the battalion shared with me.

“All of them were involved in dangerous patrol actions, and other battlefield incidents, that could have caused their deaths.

“That type of defensive warfare from a fixed location is extremely difficult for soldiers – we went through it in the Second World War; we went through it in the First World War, and we went through it in Korea; you can’t say anything good about it...

“Conditions in the field themselves were very poor, and the weather was atrocious; it was stinking hot in the summer and icy cold in the winter – the only warm place was underground.

“You might boil a cup of coffee, which you’d half drink … [and] by the time you turned around, the coffee would be frozen in your mug; it was that cold.”

Korea, December 1951. Soldiers keep watch over a snow covered Korean valley.

Korea. c January 1952. A soldier leaving his snow covered dug-out in the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), position in Korea.

He remembers how the Chinese crept through the lines in the dead of winter to leave Christmas gifts on the wire for the Australians in reserve, and how he travelled to Seoul to acquire much-needed supplies for the freezing men.

“It was towards the end of it; we had nothing,” he said. “We didn’t have any wood … and we didn’t have any space heaters.

“I was challenged [and I said] I bet you if you gave me a truck I could fill it full of heaters and wood and bring it back. So I got into Seoul, booked myself into the officers’ mess down there, borrowed a jeep, went to the American supply base outside of Seoul and said, ‘I’ve come to collect the 3 Battalion order for the reserve wood and six space heaters.’

“They said, ‘We haven’t got an order here.’ [But] I managed to talk myself into it and they delivered it to me, and I put it on the truck. I signed it off, Ned Kelly, which I thought was an appropriate thing to do given the situation and brought it back to the mess.

“There were great rejoicings, and I won the wager. But the humorous part of it was when I left Korea, and I was associated with the reparations officers in Japan, I found out they’d had about 5,000 different ‘Ned Kellys’ who’d signed for equipment all through Japan and Korea.”

Hiro, Japan, October 1952: Lt Maurie Pears MC, right, receives his MC during the Reinforcement Holding Unit (RHS) investiture parade.

When Maurie finally returned to Australia, he met and married the love of his life, Judy, and was presented with his Military Cross by the Queen at a special investiture ceremony in Melbourne.

“You can be lucky,” he said. “I was lucky to get to high school; I was lucky to get to Duntroon; I was lucky to get out of Korea; and I was lucky to find the perfect woman for me.”

Maurie went on to attend Staff College, later commanding the Corps of Staff Cadets at the Royal Military College Duntroon and the 1st Battalion Pacific Islands Regiment. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and retired from the Army in 1970, pursuing a successful business career and becoming a professional poker player.

He has since written several books about “the forgotten war” in Korea, and spent decades raising awareness about the conflict. He returned to Korea in the 1990s as part of a visit sponsored by the Korean government, and led the campaign to build a memorial at Cascade Gardens on the Gold Coast.

“Memories of war really remain with you for the rest of your life,” he said.

“Soldiers do what they are told to do, and they did a great job. They held off the enemy, and helped avoid many nasty situations, which may have occurred in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s during the Cold War.

“It was a very tense period for Australia, and I felt very proud to have been a part of it; we did a great job up there … and the men of my platoon stood out to me as great examples of what real men should be like.

“Those types of friendships last forever, they never die. They are still lasting … and I was very, very lucky to have the opportunity of training and serving with such a wonderful bunch of men.

“I hope Australia thinks as much of them as I do.”

With special thanks to the Australians at War Film Archive.