'We were very lucky, very lucky'

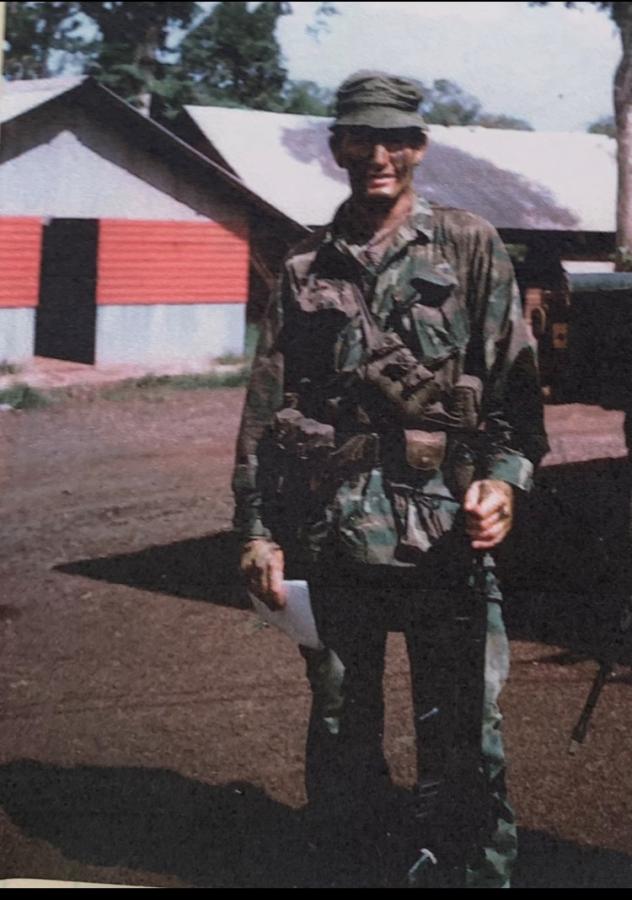

Mike Ruffin preparing to go on patrol in Vietnam. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

It was New Year’s Eve 1968, and Mike Ruffin was on his last operation in Vietnam.

He had already served in Malaya and Borneo, and by the age of 26 was an experienced SAS patrol commander.

“I am very aware of how lucky I am to be here today,” he said.

“It was near the end … my last month in country … and we were sent down to a place called the Ho Tram Cape.

“The Americans believed the North Vietnamese were coming down by sea and landing there ... infiltrating towards Saigon … so we were sent down there to verify that. And we certainly did.

“We were patrolling down towards the cape and we came across a well-used track.

“The forward scout and I went to ahead to inspect it, and there were three of four North Vietnamese coming up the track.

“Then all of a sudden the blokes behind us started firing because there were more enemy approaching.

“We’d run into what I believe was a North Vietnamese battalion … and we were engaged by a heavy weapons company.

“They had crew-served machine-guns, mortars, the whole works, and there was only five of us.

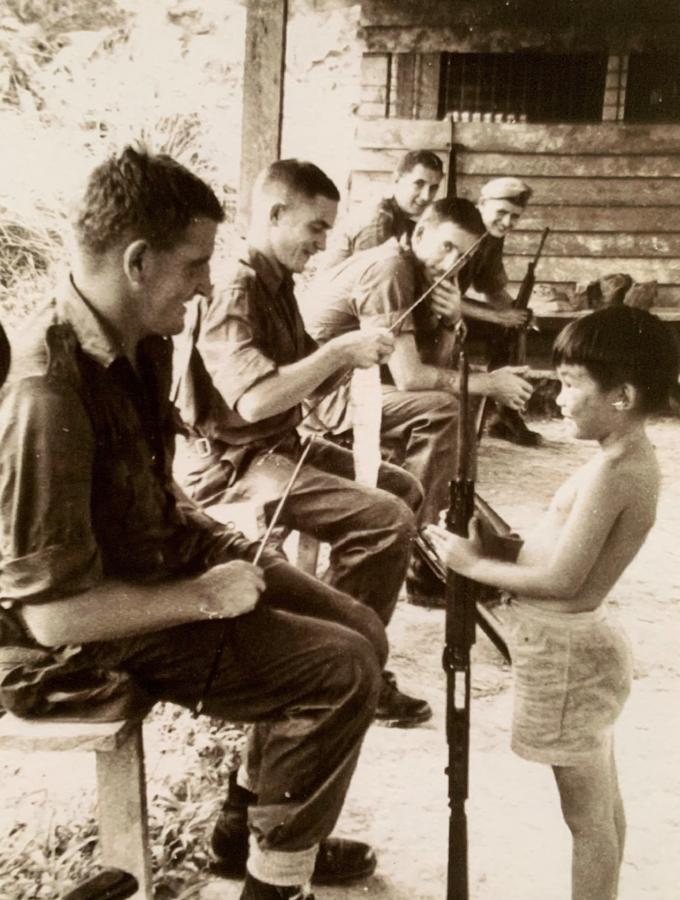

Mike Ruffin, left, in Vietnam. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

“The signaller alerted headquarters that we were in contact … and that we needed support … but there was a bit of a confusion about that too.

“Later on, when they sent the light fire to get us, they were diverted to another patrol in contact.

“We’d lost our radios by then, and we hadn't made contact for quite a while, so they assumed we weren’t still in contact, but in fact we were ….

“I’d moved the patrol into an old bomb crater whilst we were waiting for help to arrive, but the crater was filled in, so it was only about two feet deep.

“We were lying in there, and we were subjected to a mortar attack. So we took our packs off, and put them on top of the edge, so they gave a bit of height to help protect us from the mortars and the small arms fire.

“It turned out we had encountered a very large contingent of approximately 80-plus North Vietnamese… and the mortar fire was becoming heavier.

“We could see them forming up to assault us … and to our dismay, they brought forward a crew-served machine-gun and we started to receive mortar, rocket and machine-gun fire.

“It couldn’t get much worse. We were hopelessly outnumbered and it was clear the helicopter gunships would not arrive in time. We were fast running out of ammunition.

“And on our left flank, two or three North Vietnamese were crawling through the grass towards us. They were so close, we had to stop them with hand grenades.

“Realising we couldn’t defend this position for much longer, I made a decision.

“I told my patrol to leave their packs, all except the signaller.

“We were going to make a run for it.

Five members of 2nd Squadron, SAS, boarding a 9 Squadron, RAAF, UH-1H Iroquois helicopter at Kanga Pad, Nui Dat, c1968.

“The North Vietnamese started advancing towards us … and just as we stood up … a mortar bombardment came in, and a mortar round exploded, knocking us all off our feet.

“We all stood up again. We were all bleeding, but otherwise okay.

“Fortunately, we were very close to the beach, a couple of hundred metres or so, and the mortars were going into the sand.

“They were burying as they landed, and the sandy terrain around us had absorbed most of the blast, so we were just getting hit by stones and debris, but no shrapnel, or very little shrapnel anyway.

“We stood up again and ran towards the tree line, and the noise of small arms fire coming towards us was overwhelming.

“They were firing all the time, and the intensity of fire was just unbelievable. The noise, I couldn't believe it.

“How five of us could make a run for it with all that fire going on and not get hit, it’s absolutely unbelievable.

“When we got to the tree line, and we looked back, we saw the signaller had fallen behind a bit because of the weight he was carrying.

“He’s running towards us, and we're yelling out to him, encouraging him, and all of a sudden he got blown up … as a mortar round exploded, knocking him off his feet. He went sailing through the air, and when he stood up, the shrapnel had cut the straps on his pack. It fell off on to the ground, and we screamed at him to keep coming. He immediately fired two or three shots into the pack to destroy the radio, and ran towards us. He said much later on he thought we were abusing him to hurry up, but we were encouraging him.

“We then managed to slip through the enemy cordon and make our escape, aided by the rapidly fading light.

“It was terrifying. They’d tried to encircle us, and put a cordon in around us, but as luck would have it, we’d slipped right through the middle … just as they were closing in … and that was just good luck. The light was failing and that helped us enormously.”

A No 9 Squadron, RAAF, Iroquois helicopter taking off from Kanga Pad at the 1st Australian Task Force (1ATF) at Nui Dat.

After a “very eventful night and morning”, the men were “extremely relieved” to be extracted by 9 Squadron RAAF Helicopters.

“By that stage of the game, we only had about five rounds of ammunition left,” he said.

“All afternoon and all night, I thought it was just a matter of time …

“We were running out of ammunition, and when they put the assault in on us, they had 80 of them lined up, all coming towards us, all shooting, and we only had a handful of rounds.

“If they’d put in another assault on us, we couldn’t have repelled them.

“We had no grenades. We had nothing.

“We couldn't have stood another attack. We would have been gone.

“But we made it. The light was quickly failing, which was in our favour, so we made a run for it, and we got away.

“The next morning, just after first light, a reconnaissance aircraft came overhead.

“I just had what they call a URC 10 left, which is a very small ground-to-air radio. I'd been trying to get help all night on it, but I had to switch it off because the battery was running low.

“I called them on my radio, and didn't get a reply, but they stayed in the area, so I assumed they could hear me, even though I couldn't hear them.

“I said to the pilot, ‘If you can hear us, do a right hand turn,’ and he did the most beautiful 90-degree turn you have ever seen in your life.

“It was just fantastic. He was obviously trying to find us on the ground, and we had what we call a marker panel, which in my case was a piece of bright red plastic, which we used to signal the helicopters to show them exactly where we were.

“I was very loath to [use] it because it could have been seen by the enemy, so I lay down on my back and pulled it out and laid it down across my chest.

“The helicopter came right over the top of us – it was a little Bell helicopter, only two in it – and they dropped a bandolier of 5.56 ammunition, but in it was also a handwritten note with instructions saying to move 500 metres west to a landing zone, to a clearing where we would be picked up.

“That was probably the longest 500 metres of my life. I thought it was 500 miles by the time we got there, but of course it was only 500 metres.

“[I was] very relieved, to say the least. It was the closest I’d ever been – the closest any of us had ever been – to not making it.

“In hindsight, it seems inconceivable, that five men could run across 100 metres of open ground, whilst being subjected to that amount of fire and not receive a single gunshot wound.

“Had anyone of us been wounded, that would have been the end, because we would never have left a mate behind.

“We were a composite patrol, and we’d never worked together before, but we’re lifelong friends now. And we have been since way back then. We keep in touch to this day, and make sure we’re all right, so we’re still looking after each other.

“Every Anzac Day, I reflect on that experience and I am so grateful that we all survived.”

Mike Ruffin leading a patrol in New Guinea. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

Michael Ruffin was born in Victoria in 1942 and moved to Tasmania as a young child.

He had enlisted in the Army as an 18-year-old in 1960. His father, Terry, had served as a medic in the artillery during the Second World War in New Guinea, and his brother had completed National Service, encouraging him to join the Army.

“I was living in Tasmania, and when I left school the work prospect wasn't great,” he said. “My brother did National Service and he absolutely loved it, and he reckoned that was what I should do, so I signed on and I ended up serving for 26 years.”

He went on to serve with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, in Malaya from 1961 to 1963, and the SAS in Borneo in 1966.

“Coming from Tasmania, which is a tiny place, into the big wide world, it was quite an eye-opener,” he said. “When we were on operations on the Malaya–Thailand border, we felt more like mountain goats than soldiers really.”

He joined the Special Air Service Regiment after returning to Australia, and served with 2 Squadron, which had been raised for operations in Borneo.

“A few of my battalion mates volunteered to go to SAS, but only a couple were accepted,” he said.

“It was a real challenge: A, to get accepted, and B, to pass the course … But I got there.

“You've got to really want to join the regiment to get through; if you go across there just to have a look, you've got no hope.

“They make out [on TV that] your instructors are unapproachable and tough as nails, but in actual fact, your instructors on the real SAS selection course are all patrol commanders, and they'll do all they can to get you through … If you've got the heart, they'll give you the legs – and that's what they say.

“It’s very tough, it’s very arduous. And like every other SAS soldier, you're very glad you've done it, but you're also very glad it's behind you.”

Mike Ruffin, left, in Borneo in 1966. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

Kuching, Borneo, 1966: The late Prime Minister Harold Hold visiting 2 Squadron. Mike Ruffin, pictured right, closest to the car. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

He was promoted to sergeant in 1966, and was an experienced patrol commander by the time he arrived in Vietnam in February 1968. He and his wife Melva had been married just six months when he left.

“We were part of the advanced party, and we'd been briefed regularly on the situation, so we knew a lot about it,” he said.

“We flew from Perth airport into Ton Son Nhut [Air Base] in Saigon, and our squadron followed us about two or three weeks later.

“The first thing you probably noticed was the heat … But it's a very busy place, Ton Son Nhut Airport, and it’s quite amazing. As a plane would come in, another one would take off underneath it.

“There were people going everywhere.”

Based out of the Australian Task Force Base at Nui Dat, he led reconnaissance patrols in Phuoc Tuy Province.

“There was a lot going on,” he said. “So you didn't get much rest time. We would come off an operation, have a day off, then prepare for the next one; and that's all.

“And that happened the whole 12 months … so it was all pretty tightly knit.”

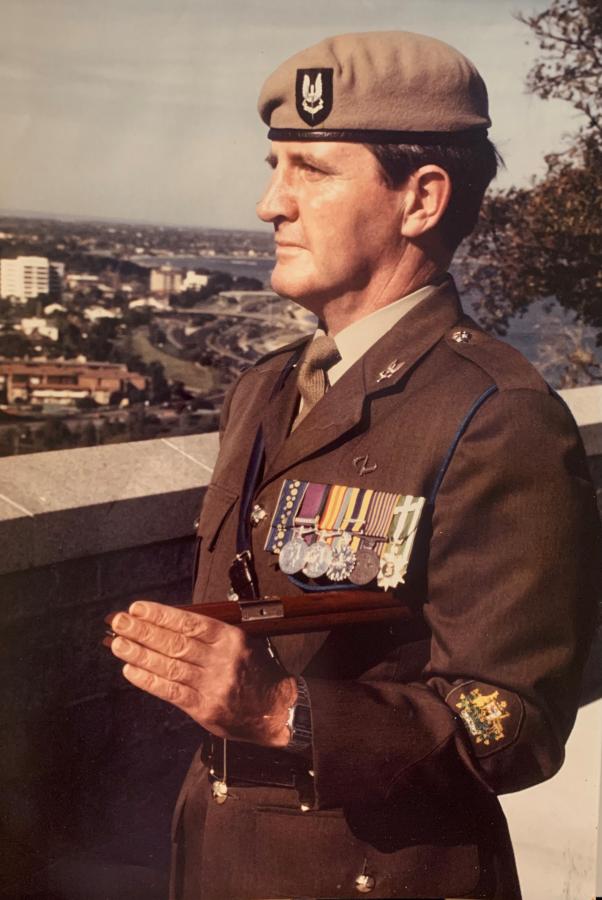

Mike Ruffin was also Regimental Sergeant Major of the SAS. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

He remembers coming home to Australia on an American R&R flight in 1968 and being confronted by anti-Vietnam protesters.

“We got to Sydney airport, and there was a protest going on,” he said. “I didn’t take much notice of it to be quite honest, but it was quite big, and quite loud.

“This idiot threw a tomato at me, and I only had the shirt and trousers that I was standing up in.

“I was furious. The tomato was splattered all over my shirt, and as I say, that was all I had.

“I grabbed him, and this policeman grabbed me, and said, ‘Don’t! You’ll spend your R&R in the watch house … I’ll look after him.’

“And when I looked back, this policeman and this lout were sharing a cigarette and laughing together.

“I couldn’t believe it. It was very distressing.

“I mean, if you want to protest, protest by all means, but don’t pick on the people who are just doing their job.”

Returning to Sydney on his way back to Vietnam, he was shocked to find he was also refused entry to a Sydney RSL.

“After my R&R in Perth, the petrol strikes were on, and I was stuck in Sydney, 3000 kms from Perth, with nothing to do, for about five days,” he said.

“I ran into an ex-SAS bloke from 3 Squadron … and he took me down to the RSL in my uniform because again, that’s all I had. The doorman said to him, ‘You can come in, but your mate can’t … the RSL doesn’t support the Vietnam War.’ And that was probably the biggest shock I had during the Vietnam War, that the RSL wouldn’t let me in, in uniform.”

He was grateful when he finally returned home from Vietnam in February 1969.

“It was fantastic [to be back in Australia],” Ruffin said.

“That last patrol was the closest I’d come to not making it back, so it was a real relief to be back.”

Mike Ruffin OAM has dedicated his life to serving others. Photo: Courtesy Mike Ruffin

He went on to serve as an instructor at the Officer Cadet School at Portsea from 1976-78, and as Company Sergeant Major, 6 Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, from 1978-79. He also served as an instructor at the School of Infantry in 1980, and as Regimental Sergeant Major of the Special Action Forces Directorate from 1981-82.

He was also Regimental Sergeant Major of the SAS from 1982 to 1986, and in 1985 was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to the SAS.

He has been involved with Legacy and RSL sub-branches in Perth for the past 30 years, and is an active member and past president of the SAS Association.

He was honoured to be invited to speak at the Dawn Service at the Australian War Memorial.

“Anzac Day is a very important day in our national calendar,” he said.

“There is a lasting bond with those who have served, and Anzac Day is the day to enjoy each other’s company, reminisce and remember those who are not with us.

“I am honoured to have been invited here, and I am very proud to have worn our country’s uniform.

“The Memorial is treasured by all servicemen who are lucky enough to go there … it’s hard to find words to describe it.

“We must try and avoid war at all costs … but we must never forget...

“Mateship meant absolutely everything.

“And it’s very important that we remember those who have given their all for their country.

“We were very lucky, very lucky, and that’s probably a good word for it.

“But I’ve always believed it was our excellent training that saved the day.

“I’m very grateful that I survived, and that I get to live in this paradise that we call Australia.”