'I would do it all again in a heartbeat'

Advisory/warning: the following story contains distressing

content and graphic descriptions.

Miles Wootten has seen the best and worst of humanity.

He spent his 22nd birthday in Rwanda as an Australian peacekeeper, cleaning up after an atrocity that had left almost a million people dead and millions more homeless.

“I missed my first wedding anniversary, my family’s first Christmas, and my daughter’s first birthday, but I would do it all again in a heartbeat,” he said.

“These people had nothing. They were eating bark off trees and grass from the ground …

“The whole place was still riddled with dead people and it was absolutely filthy.

“But I’d gladly go back … I’d gladly do my time over … everything that we went through and all that we did … to help those kids who had lost everything … and let them know someone cares.”

Miles Wootten with a small child in front of a stall selling paintings in a Rwandan street.

A private in the Australian Army, Miles was one of more than 600 Australian troops who served in Rwanda in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide.

He had joined the army in 1991, just a few years before the genocide began.

“Work was few and far between,” he said. “I’d not long finished high school, and when I was at Centrelink looking for work, I saw a poster for the army. My cousin had already joined, and she seemed to like it, so I put an application in, and by April I was in. It was a spur of the moment thing. My great-grandfather served in the First and Second World Wars, and my dad was in the services, but I had no inkling whatsoever.”

He was 21 years old when he deployed to Rwanda as part of Operation Tamar, the Australian contribution to the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR II). Nothing could prepare him for what he would encounter.

“One of my friends was a medic, and he called me the night before, and said, ‘Do you know you’re going to Rwanda? You’re down to have a medical tomorrow,’ and that’s how it happened,” he said. “I actually broke the news to people at work the next day … and within seconds the phone rang.”

Miles, pictured with his daughter, just before he left for Rwanda. Photo: Courtesy Miles Wootten

Miles landed at the airport in the Rwandan capital, Kigali, in August 1994 and was immediately confronted by the harsh reality of war.

In the three months before he arrived, more than 800,000 people had been brutally murdered and killed; almost two million fled their homes and became refugees. It was one of the most concentrated and brutal episodes of mass, orchestrated killings of the 20th century.

The trigger for the genocide came on the evening of 6 April 1994. Decades of tensions between Rwanda’s two main ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi, erupted into violence when an aeroplane carrying Rwanda's Hutu President Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down while coming in to land at Kigali airport.

Hutu extremists accused Tutsi rebels of carrying out the attack. Within hours, thousands of Hutu militias and Rwandan troops, fuelled by decades of anti-Tutsi propaganda, began attacking ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus. As the violence escalated, “hate media” encouraged ordinary people to take part in the slaughter, urging them to take any weapon they could find to kill or maim their neighbours. The most common weapons were machetes. Neighbours killed neighbours, teachers killed former students, and people were buried or burned alive. Over the next 100 days, hundreds of thousands of people were massacred in their homes as well hospitals, in fields and roadside ditches, and in stadiums and at checkpoints. Those seeking sanctuary in churches or treatment in hospitals were butchered. The slaughter was so widespread that thousands of bodies washed down the Kagera River into Lake Victoria in Uganda and had to be buried in mass graves to stop the spread of disease.

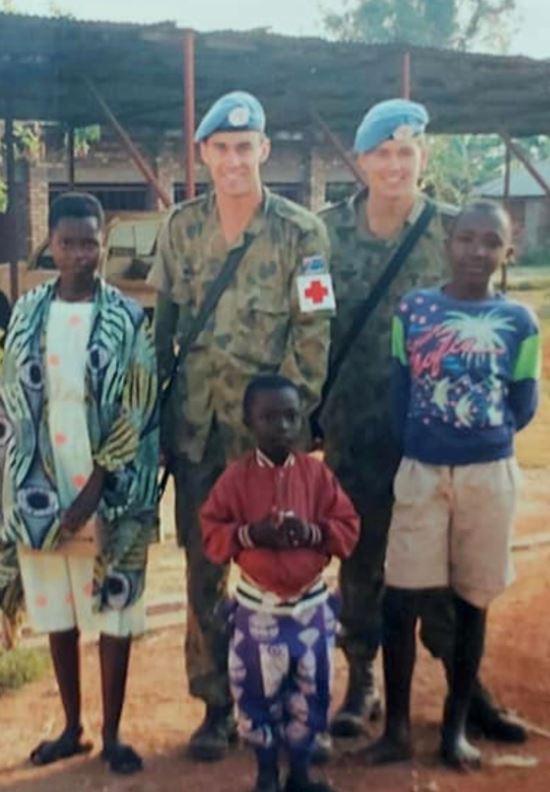

Miles with fellow soldiers in Rwanda. Photo: Courtesy Miles Wootten

“It was horrific,” Miles said. “I went in as part of the advance party, and our role was to get the main hospital at Kigali clean and operational again for our troops, and get the barracks up and running.

“The whole grounds were littered with the filth from the war… and next door was a mass grave.

“The first weeks in country were the hardest part of my life … We were working 16–18 hour days … and our rifles had to be within an arm’s length at all times.

“I lost ten kilograms in the first two weeks … but this was nothing compared to what the Rwandan people had been through.”

Kigali, Rwanda, 1994: Miles "Woody" Wootten, with Scott "Bob" Meredith, and Ty "Casper" Smith, in downtown Kigali, near the market place.

A driver in the Royal Australian Corps of Transport, Miles was given the job of scrubbing the morgue.

“A lot of the places that got hit first were the hospitals because they were easy targets and they had back-up generators and the like,” he said.

“All the toilets were full to the brim, and there was unexploded ordinance everywhere.

“There were blood-stained walls and floors, and you could tell the execution rooms, and the torture rooms, and the rape rooms.

“The morgue still had three people in it when I went through and they had been there since the war. I said to a mate, ‘I thought morgues were supposed to be white,’ and he said. ‘They are,’ but this one was all black. We kicked the floor, and it was an inch thick with all the blood and dead flies and everything else.”

Photos: Courtesy Miles Wootten

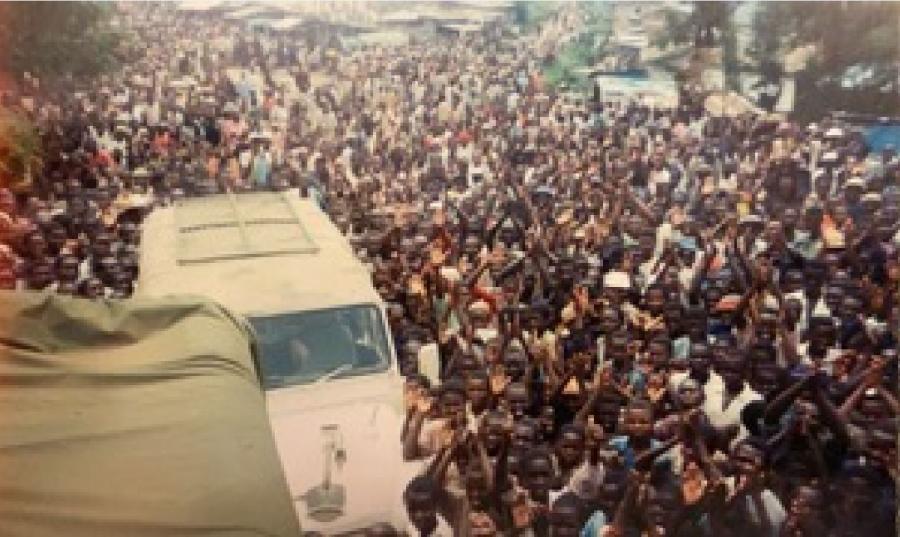

He remembers travelling to the Kibeho Refugee camp for the first time.

“We came over a rise, and there were a million people,” he said. “I stopped and I looked at my co-driver, and said, ‘So that’s what a million people looks like.’

“You can’t describe the sights, the sounds, the smells of a million people … a million people on top of each other.

“We stayed at the Kibeho camp for a few days, trying to weed out some war criminals, and at night, I found one of my friends coming in through the wire alone.

“I questioned him and told him how crazy it was. I said, ‘Mate, what are you doing?’ And he said, ‘I can’t stand it. I can’t stand the crying. I don’t care if I don’t eat today. These people are getting fed.’

“We had these French ration packs – pâté and biscuits – and he’d been giving them out under the cover of darkness.

“I laughed, and I said, ‘Well, don’t go alone; there’s a heap more over here,’ so we went back out, and we gave out … these French ration packs.

“We were giving out food where we could, especially to the kids who were crying, and to the mothers.”

Miles Wootten, right, in Rwanda. Photo: Courtesy Miles Wootten

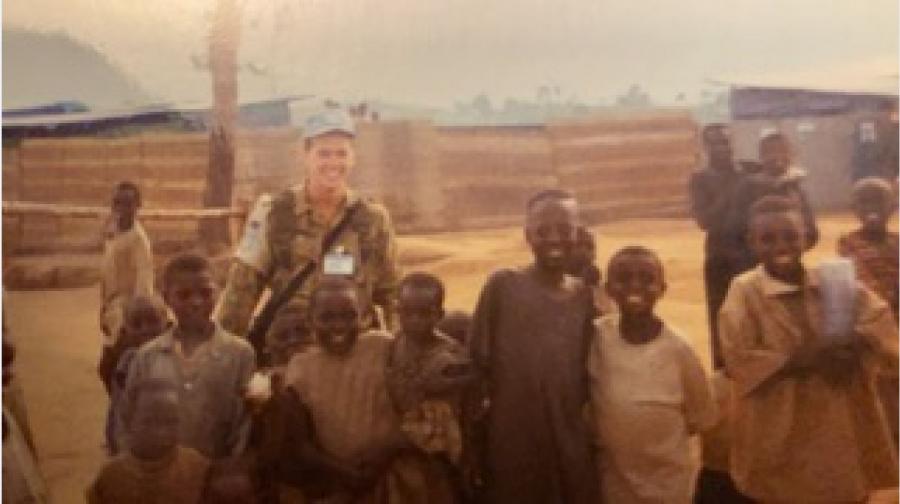

Miles volunteered to be the duty driver over Christmas and New Year, and spent his time driving through the streets, giving food and lollies to the children. He decorated the white UN Range Rover with balloons and added tape so that it read “FUN Police”.

“One of the hardest things was the kids,” he said.

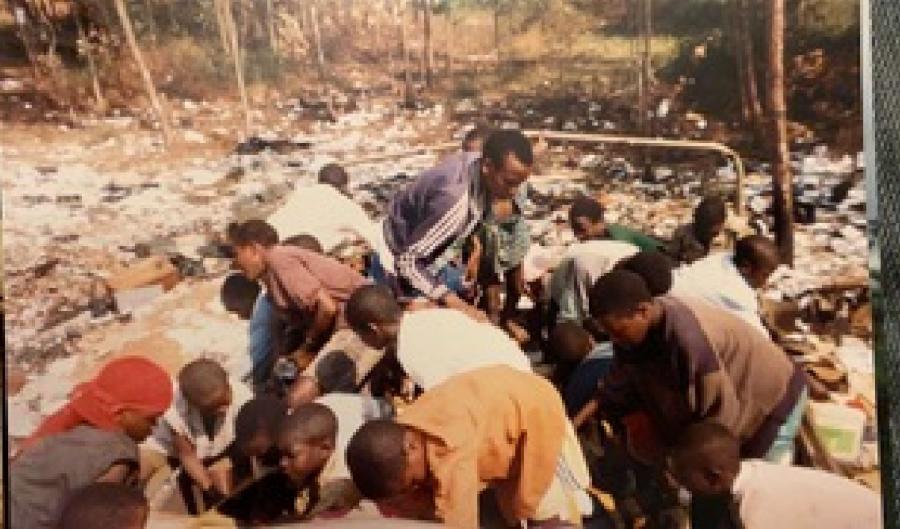

“There was extreme poverty, and the rubbish tip was one of the worst places to go. The first time we went with a tip truck, I couldn’t even stop before the kids who lived at the dump were climbing all over the truck looking for food. We learned fairly quickly to take food and water in first in a separate truck to hand out to them so they wouldn’t climb on the truck as it was tipping.

“On a break, I heard a familiar tune being tapped out on metal. I looked over the fence to see a girl around 12 in a wheel chair who was missing both legs from the knee down and a little boy around two who also was missing a leg. He had the bottom of a wooden crutch cut up as a fake leg while he was learning to walk again. It dawned on me what the song was and I started to sing, ‘She’ll be coming round the mountain when she comes.’ The girl looked at me with a huge smile on her face, and we sang with her for a while, and it was like we made her forget her troubles just for a moment.”

Miles Wootten with children in Rwanda. Photo: Courtesy Miles Wootten

He remembers sharing a loaf of bread and a bunch of bananas with a boy he met standing on the side of the road. “He was just ecstatic,” he said. “And I like to think that I really helped that kid out, not only feeding him for the day, but giving him money to survive.”

Miles returned to Australia in February 1995, but life would never be the same again.

“I can still see the look on my daughter’s face when I got home,” he said. “She was one, and I was putting her in her car seat. She’s sitting there, looking at me, with this intense look, and then all of a sudden it clicked, and a huge grin came up on her face, and her arms came out as she realised, ‘I know who you are! You’re my dad.’ And that was the best part of coming home.”

Miles Wootten with a child delivering aid in Rwanda. Photo: Courtesy Miles Wootten

For more than two decades, he kept his memories painfully private, but smells, sights and sounds would transport him back to Rwanda.

“I hate flies, even now,” he said. “And to this day, I can’t stand having flies in my house.

“I can still see and smell that room [at the hospital], and as I speak about it, I can see and smell it all again … I had a surgical mask on infused with eucalyptus oil to try to stop the smell, but you could still smell it … And the heavy and over powering smell of that building will be with me till the day I die.

“My wife sent me a tape of our daughter crying late one night and she said it was so I could hear her … Little did she know that was the sound I heard most.”

In 2018, he returned to Kigali to confront his demons with his brother Steve. The trip was part of a delegation organised by the Rwandan consulate in Melbourne and the Rwandan Development Board. He hoped returning to the country and seeing how it had changed would help him with his PTSD.

Crowds of people gather around the trucks in Rwanda. Photo: Miles Wootten

“Before I returned, I had problems with a number of demons over the years,” he said. “Nightmares, waking up not knowing where I am, the images that pop in my head at random times, feelings of loss and abandonment, mood swings and crying at simple things or whilst watching TV or movies… For ten years I hid it from just about everyone. I just carried on as if there was no problem, with a smile on my face hiding the real pain and issues. Good friends had no idea I have PTSD …. I withdrew from day to day events and shut myself off from the world trying to hide from the hurt and pain.”

Seeing Rwanda as a much more peaceful and stable country than when he left it meant a lot.

He returned to Rwanda again in 2019 with his two daughters and his son-in-law to mark the 25th anniversary of the genocide.

Tattooed on his arm are the Australian and Rwandan flags, and a shield bearing the word Miryango – the Kinyarwandan word for family. A faded red poppy is for the 800,000 people who were brutally murdered and killed.

On his other arm, a fighting kangaroo wearing a slouch hat has its own tattoo representing the number of Australians who served, and Par Oneri, the Royal Australian Corps of Transport motto: “Equal to the Task”.

“I’ve had Rwanda in my head and my heart since being there, and now it’s on my sleeve so other people can see it,” Miles said.

His story is told at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra as part of Ink in the Lines, a temporary exhibition sharing stories of Australia’s military veterans through their tattoos.

The exhibition features personal stories from men and women who have served with the Australian Defence Force in conflicts and peacekeeping operations from Iraq and Afghanistan to Rwanda and Somalia.

“For years I’d born the scars on the inside, and I wanted to put them on the outside so people could see them,” he said.

“Never ever did I think they would be there in the Memorial or get the attention that they have.

“The tattoos are a bit of recognition for our troops, but also for the country and for what they went through.

“There are still people who don’t know we were there, and there are still people who don’t know the extent of what we did, or what the Rwandans went through…

“It’s not that long ago, but we’re continually forgotten. I’ve seen newspaper articles about all the service that Australians have done, and Rwanda’s never there; more than 600 people went and gave their all in that country… How do you forget them?

“I’ve had quite a few people within the RSL say to me, you didn’t go to war, you don’t belong here, and my reply each time is, I’ll swap you any day … I’ll go to war, you go clean up a war zone … because until you’ve done what I’ve done, don’t even try and compare it… That’s when their opinion changes and that’s when they sit back and contemplate what they’ve just said.

“To the people who think peacekeepers don’t belong I say, ‘Talk to peacekeepers, find out their stories, don’t just write them off as every medal tells a story.”

Miles with fellow soldiers in Rwanda. Photo: Courtesy Miles Wootten

Twenty-five years on from the genocide, the Australian troops who served in Rwanda were awarded a Meritorious Unit Citation in recognition of their extraordinary courage, discipline and compassion. For Miles, it was particularly special.

“It was a beautiful day and that was effectively our welcome home, 25 years later,” he said.

“Without us being there, I don’t think Rwanda would be the country it is today. We helped them rebound and get their dignity back and find their humanity again, but we also helped a lot of people physically as well which is just the best.

“When you go to Rwanda and you see what Rwanda was compared to what it is now, it is a success … and Australian troops did a really good job.

“I look at what we did, and the amount of people that we helped, and I’m very, very proud.”

Ink in the Lines is on display at the Memorial until 25 July 2021. For more information, visit here.

Defence All-hours support line – The All-hours Support Line (ASL) is a confidential telephone service for ADF members and their families that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week by calling 1800 628 036.

Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling Service provides free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. They can be reached 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit the Open Arms website for more information.

DVA provides immediate help and treatment for any mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. If you or someone you know is finding it hard to cope with life, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254. Further information can be accessed on the DVA website.

Australians have been actively involved in peacekeeping operations since 1947 when four Australians were deployed to Indonesia as part of the first UN peacekeeping mission. Since then, Australia has made an estimated 40,000 individual deployments to more than 60 peacekeeping operations around the world. Currently, peacekeeping operations have only a small amount of space allocated to them in the Memorial’s Post-45 galleries. The Memorial is planning to modernise and expand its galleries as part of a major new development project to create the space needed to tell the stories of peacekeeping operations such as Somalia and Rwanda in more detail, as well as the 60 other peacekeeping missions on which Australia’s soldiers, sailors and aviators have served with courage and compassion. To learn more about the development project, visit here. To share your story, email gallerydevelopment@awm.gov.au