Mutiny in Stalag XIII-C

“Never lose a moment’s sleep over me,” wrote Lance Sergeant Ronald Chambers, eager to reassure his family of his wellbeing. Between August 1941 and May 1945, Chambers sent 85 letters and postcards to his parents and siblings, writing of new friendships, cricket tournaments and the over-abundance of parcels sent to him while he was a prisoner of war.

Chambers would endure nearly four years of imprisonment across the German Reich, be assaulted, arrested and charged for active mutiny, and spend months on end in solitary confinement.

But he was convinced one day he would be going home.

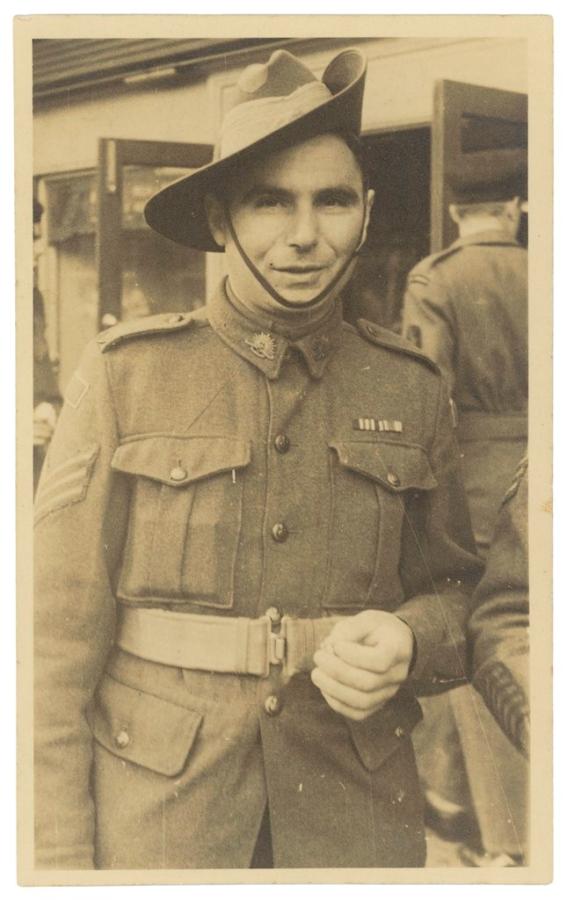

Lance Sergeant Ronald Chambers c.1941-1945. Photographer unknown. (P12720.001)

An engineering surveyor from Berwick, Victoria, Chambers enlisted in May 1940 at the age of 25, and was a natural fit for the Royal Australian Engineers. By October, he was serving with the 2/8 Field Company in Palestine. Chambers distinguished himself during a skirmish at Derna on 27 January 1941. Showing “great courage and devotion”, he proceeded through a minefield while under enemy fire to disable a kilometre long stretch of road, enabling Australian units to advance; for this, he was awarded the Military Medal.

On 13 April 1941, Chambers and the 2/8 Field Company were sent to Greece, tasked with managing “demolitions, culverts, cratering and rock-falls”. After a disastrous few weeks, the Allied forces were compelled to withdraw to Crete. Their reprieve was short lived, as German paratroopers swept through and seized the island within the month. The 2/8 Field Company diary records, “Embarkation 30 May – a party embarks but includes no officers. Many left behind.”

Chambers was one of 3,109 Australians to miss the evacuation of the island and be taken as a prisoner of war.

German paratroopers parachuting onto the village of Suda, Crete, 20 May 1941. Photographer unknown.

Chambers spent the following weeks in a miserable Dulag (transit camp) in Salonika, Greece, before making the week-long journey to Germany in a cattle-truck. There, he was allocated to a Stalag (prisoner of war camp) – Stalag XIII-C in Hammelburg, Northern Bavaria – and given a labour assignment in the village of Lebenhan.

Approximately half of all Australian prisoners of war were delegated to Arbeitskommando (labour units) during detention in the German Reich, typically working in the agricultural or manufacturing industries. For Chambers, work provided a relief from the monotony of imprisonment and an opportunity to learn a foreign language: “I teach the children English, milk the cow, and generally fill the day with work which all helps the time to pass quickly.”

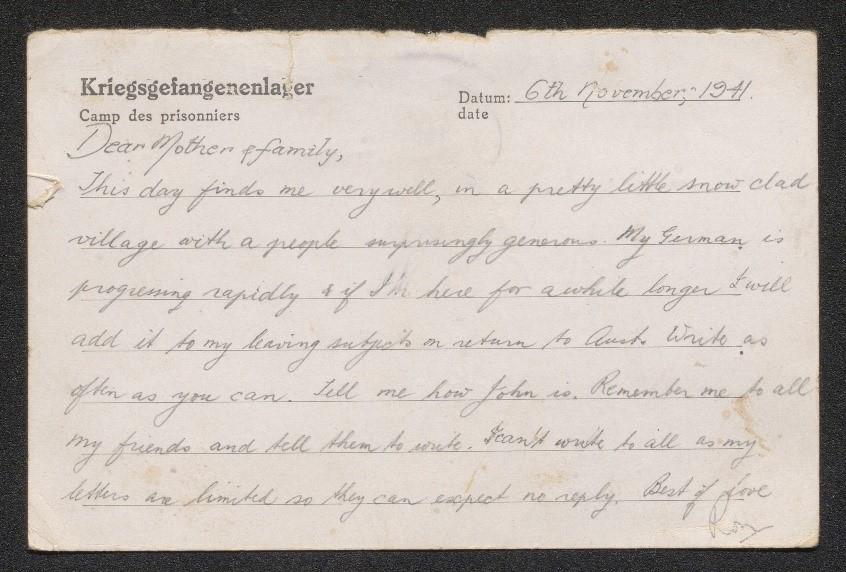

One of Chambers’ prisoner of war postcards, dated 6 November 1941, describing his work with the Arbeitskommando.

Early life in Stalag XIII-C looked promising. After six months, Red Cross parcels began to arrive; Chambers recorded that the men were well-fed and their spirits high, despite a brutal adjustment to the wintry German conditions.

In early 1942, however, German authorities began to impose harsher stipulations on the Arbeitskommandos, requiring prisoners to work to the point of exhaustion. Chambers protested their treatment and organised a strike; German authorities were alerted and soon arrived at the scene.

Chambers described that “After a certain amount of physical violence and the bluff of a firing squad,” he was arrested and escorted to a holding prison. On 15 May 1942, he was found guilty on six counts of active mutiny at a military court in Würzburg. Permitted no witnesses, he was sentenced to five years imprisonment with hard labour (the hard labour sentence was later withdrawn).

Twelve harsh months in military prisons across northern Germany and Poland, where other political and military offenders were held. Conditions were bleak and his future increasingly uncertain. Chambers spent roughly two months in solitary confinement, and another two in “leg irons, handcuffs and dark cells”.

A view of the moat and drawbridge at Stalag XXa in Thorn, Poland, c. 1942–1945. Chambers was held here for several months. Photographer unknown.

Permitted to write infrequently, Chambers’ letters to his family were reassuring and cheerful:

“Isn’t it funny, me in a jail! And for such a term. At least I had publicity, nearly all the POWs have heard of such a criminal.”

“Have been in better places, but it is not too bad.”

When writing to his friends in Berwick Shire Council, Chambers outlined his circumstances:

“For the last 6 months I have been in a punishment jail following a court martial on a charge of inciting mutiny. My sentence is 5yrs imprisonment […] I am not the only Australian here, but at least I hold the record sentence.”

“As you can imagine we are all putting on weight, the treatment is excellent and we get breakfast in bed.”

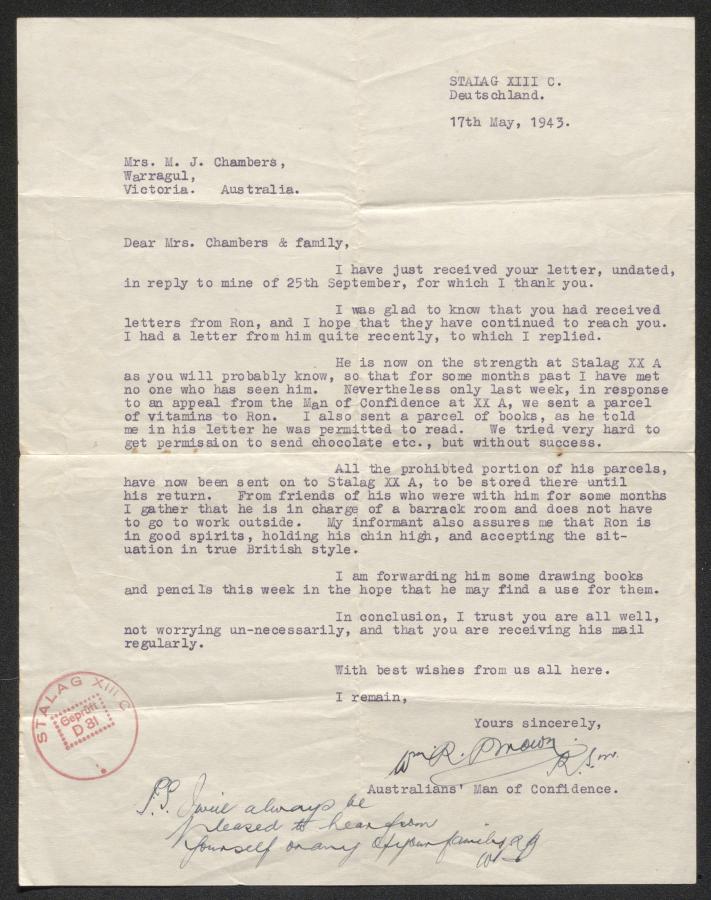

A May 1943 letter updating Chambers’ family from the Man-of-Confidence representative of Stalag XIII-C, Warrant Officer William Brown. (AWM2023.6.192-0085)

At a retrial in May 1943, Chambers was acquitted of all but one charge, and his sentence was reduced to two months’ imprisonment, time served. During the year-long ordeal, Chambers lost nearly half his body-weight, dropping from 83 kg to 46 kg. Upon his return to Stalag XIII-C, Chambers was treated as a celebrity:

“the boys are giving me a wonderful time. Instead of 5 years I got 2mths this time, so actually did 11 ½ months too much, but am so happy that I can forget about that, and it was such a ‘wonderful’ experience that now that it is all over I can say it was worth while.”

A group of Australian prisoners of war at Stalag XIII-C, 1943. Chambers can be seen standing third row, seventh from the left. Photographer unknown.

In his letters home, Chambers’ character and tongue-in-cheek sense of humour remained undiminished:

“Another year and still my ‘holiday’ continues. I never thought I would be able to spend so much time touring Europe – splendid eh?”

“I still have my hip flask. It has contained at various times whisky, water, coffee, tea, wine, rum, cognac, olive oil etc. Now it is empty. However one can hardly expect whisky when a POW.”

Chambers’ metal and copper hip flask, engraved with the Rising Sun badge and his name. (REL50558)

Despite their hardship, spirits remained high among the men of Stalag XIII-C. Chambers notes that cricket matches between Australian and British prisoners were common, as were musical concerts and theatrical performances. Chambers describes his love of snow, his proficiency in making porridge, and savouring the first roast potatoes he had eaten in years.

Menu and programme for a Christmas dinner held by Australian prisoners in Stalag XIII-C on 23 December 1941.

Chambers and other Allied prisoners of war were transferred from Hammelburg to Stalag 357 in April 1944. In the final months of the war, the prisoners suffered from over-crowding, ration shortages and a frustrating lack of news.

Chambers was finally liberated from Stalag 357 by British forces in May 1945.

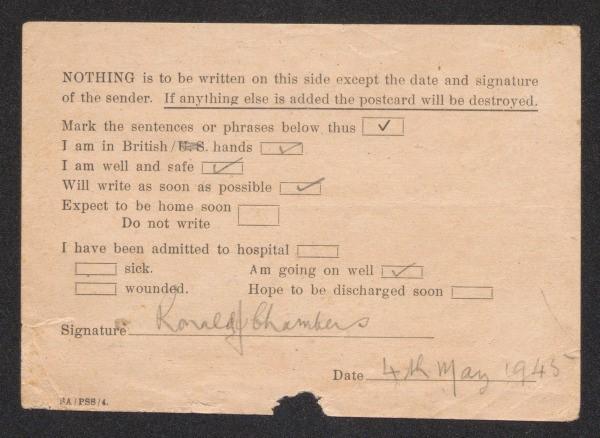

A recovered prisoner of war postcard sent to Chambers’ mother on 4 May 1945, indicating he had been liberated by British forces. (AWM2023.6.192-0186)

After his rehabilitation and discharge, Chambers returned home to Victoria and his family in late 1945. He was followed to Australia by a young German woman, Gertraud “Wandel” Krahnke. The two had struck up a friendship during Chambers’ captivity when Wandel passed food to the Australian through the fence of his prison camp. Wandel emigrated to Australia in 1948 and was reunited with Chambers; they were married shortly after. The couple had two children together, and put the hardship of the war-years well behind them. As Chambers reflected, “One dreams of … the first week in Australia, the years to come, and of course, one’s people and friends become very dear – and that makes the future worthwhile.”

___________________________________________________________________

Ronald Chambers’ letters and postcards are held by the Australian War Memorial as Private Record collection PR06393.