A woman interrupted

Nora Heysen in her studio completing paintings which were commenced in New Guinea.

Nora Heysen was the first woman to win the prestigious Archibald Prize and the first woman to be appointed as an Australian official war artist.

Her father, the renowned landscape artist Sir Hans Heysen, didn’t want her to go. He told her that she would see things that she would never forget. And he was right.

The story of Flying Sister Marie Craig would have a lasting impact on her.

Known as the “Flying Angels”, the Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service Air Evacuation Transport Unit flew in and out of combat zones delivering supplies and evacuating the wounded to Australia.

Nora was sharing quarters with some of the sisters, and was keen to paint a portrait of Flying Sister Beryl Chandler, when she met Marie.

“Nora had approached me many times to sit for her and for one reason or another I did not want to,” Beryl wrote in her memoir, which is now held in the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial.

“One day there was only [Marie], Nora and myself in the Officer’s Mess when once again Nora asked me to allow her to paint me

“Again I wasn’t keen, and dithered whereupon Marie said to Nora: ‘Look Nora, you might as well paint me, I’ll pose for you. This job is going to kill me anyway, and at least people will know what Marie Craig looked like.’

“I was aghast at this statement because she seemed to mean it, and I remember saying to her, ‘Marie, it is a volunteer job, and no one would mind if you transferred to ground duties’ … but she was adamant that she was going to fly on, and she was just as sure she was not going to make it home to Australia. ‘No Chan, the writing’s on the wall. I am just not going to come through.’ She loved the work, it gave her immense satisfaction, but she had this strong premonition that she would be killed.”

Sister Marie Craig, 1945. Sister Marie Craig served with the Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service, No 2 Medical Air Evacuation Transport Unit.

Marie Craig sat for Nora three days before peace was declared in the Pacific. A month later she was lost along with captain, crew and all on board when the plane she was on disappeared on a flight from Biak in September 1945.

It was found some 25 years later, on the side of a mountain, 14,000 feet above sea level in the Carstensz ranges in Indonesian Papua.

Nora sent the portrait to Marie’s mother.

Today, it is part of the National Collection at the Australian War Memorial, one of more than 170 works Nora created for the Memorial during her commission as Australia’s first female official war artist.

“That’s why she felt she was doing something important,” biographer Anne-Louise Willoughby said. “And now, here we are in 2019, talking about Marie Craig, and we wouldn’t be if Nora hadn’t made that drawing.”

On 10 July, Willoughby will present a free public talk at the Memorial, War and love – Nora Heysen, focusing on Heysen’s experiences as Australia’s first female official war artist.

Willoughby was nine years old when she first discovered Nora’s father, Sir Hans Heysen, and his work on a school excursion to the Western Australian Museum.

“I was on the staircase, and I was very taken with a very large landscape painting by Sir Hans Heysen,” Willoughby said. “It’s an iconic work, Droving into the light, and that painting made me understand what art can do for you, and how it can transport you to another place.”

Official war artist Captain Nora Heysen at 106th Casualty Clearing Station.

But it was not until the 1990s that Willoughby discovered Nora’s work.

“By chance, when I met my husband his best friend was the grandson of Sir Hans, and his aunt was Nora Heysen,” she said. “We visited his house in the south-east of Australia and I was walking down the hallway and I saw these extraordinary pictures. I knew some of them were Hans Heysen’s, but I knew some of them weren’t … and I thought, ‘Why don’t I know who this woman is?’”

Willoughby soon realised she wasn’t alone and set about learning more about Nora Heysen and her art.

“I kept crossing paths with Nora,” Willoughby said. “And I felt very strongly that this woman’s achievements needed to be known.”

She spent more than four years researching and writing Nora’s biography, Nora Heysen, a portrait, with the support of the Heysen family.

“Nora was possibly one of the most determined women I’ve ever got to know,” Willoughby said.

“She was born in 1911, and from a very young age she was working. By the age of 16 she had sold her first oil painting to Dame Nellie Melba, and by the age of 22 she was in every major art institution in the country. She didn’t’ stop working until almost just before she died.”

Official war artist Captain Nora Heysen.

The fourth child of Hans and Selma Heysen, Nora was born in Hahndorf, South Australia, and received her earliest art training from her father at their family home, “The Cedars”, in the Adelaide Hills.

“She had an irrepressible urge to draw or paint from a very young age, but there were a lot of obstacles that got in her way,” Willoughby said.

“I think she was a woman interrupted. She was interrupted by the teachers that she was exposed to in London when she was a student; they didn’t know what to make of this incredibly talented woman and just tried to put her in a box.

“She was interrupted by winning the Archibald Prize; most people would use that as a platform to promote themselves, whereas Nora was very shy and just wanted the press to go away.

“She was also interrupted by her wonderful war commission; and by interruption, I don’t necessarily mean it was a bad thing.

“And then she was interrupted by love; she fell in love and subjugated herself to the life of a 1950s housewife, but she still produced her work.

“And then she was interrupted because her husband left her for a younger woman; and then she was also interrupted by the loss of her informally adopted son to an AIDs-related illness.

“But what it did in every case was make her more productive and more driven.

“Every time, in those moments of grief and loss, she returned to her art as her solace and her regeneration.

“It was her and art; they were inseparable, and it was her saving grace.”

Nora Heysen's Transport Driver (Aircraftwoman Florence Miles), 1945.

Nora returned from studying in London in 1937 and became the first woman to win the prestigious Archibald Prize for portraiture in 1938.

When the Second World War broke out, she was determined to do her bit. Two of her brothers had joined the air force, and she wanted to serve as well.

“She was a pacifist, as was her father, but she felt very strongly that she needed to make a contribution,” Willoughby said. “She would see the shiploads of young men leaving Sydney Harbour, and she was always devastated by the trainloads of soldiers moving out to go down to Melbourne to leave or go up to Queensland for training. And she thought, ‘I have to do something.’

“She went to the navy, and tried to volunteer to make sandwiches, but she was sacked because she was too generous with the filling. She said she thought this was a great injustice because these young men should be given the very best that they could possibly have, and as much of it as possible.”

It was then that Heysen decided she could contribute through her art.

“No woman had ever applied to be an official war artist,” Willoughby said. “She had seen photographs and images that had been coming out of Europe and thought, ‘This is how I can make my contribution: I can paint, and I can draw, and I can record the service of these people who are making this sacrifice for our country.’

“She would still be doing what she loved doing, but she’d also be making a contribution.”

Theatre Sister Margaret Sullivan, 1944. Sister Margaret Doreen Sullivan, of 111 Australian Casulty Clearing Station wearing mask, cap, gloves and gown for operations.

Nora applied with the support of her two of her mentors, Sydney Ure Smith and Louis McCubbin. A close friend of her father’s, Ure Smith was a prominent publisher and artist as well as the chairman of the War Art Council. McCubbin also lived in the shadow of a famous father – the Australian impressionist Frederick McCubbin – and was the director of the National Gallery of South Australia as well as a board member of the Memorial.

“She was busting to get to some action, but it took a while for the war art committee and the army to reach an agreement on what her rank would be, and how she would be paid,” Willoughby said.

“Lieutenant Colonel John Treloar [the head of the official war art scheme] believed that Nora should be paid the same as the male war artists, but the army disagreed.

“They couldn’t come to terms with the notion of paying a woman the same amount of money, but Treloar and the other members of the war art committee couldn’t come to terms with not paying her the same.

“It was a big issue, and it delayed Nora from getting under way, but it was finally determined that she would receive equal pay… The Memorial would fund the shortfall because they felt that strongly about it.”

Matron Annie Sage, 1944. Sage was Matron in Chief AANS. ART22218

Nora began her commission by painting studio portraits of the heads of the women’s services – Matron Annie Sage, Colonel Sybil Irving, Lieutenant Colonel Kathleen Best, Lieutenant Colonel May Douglas, and Matron Annie Laidlaw – but would later serve in Finschhafen, Lae, Morotai, and Borneo.

“She was very patriotic, and very proud,” Willoughby said. “She felt so deeply about the horror of war and the shocking loss of life, and she was humbled by the work that these people were doing.

“Matron Annie Sage was very taken with Nora, and she wanted her to be able to go to the casualty clearing stations in New Guinea and into the tropics of northern Queensland to record the nurses’ work there.

“Nora was appointed to the Australian Women’s Army Service, but the AWAS was only allowed to serve on home territory, so she was put on the Special Army List which allowed her to travel overseas to record the work of medical personnel in the casualty clearing stations.

“When she arrived in Finschhafen, the nurses wouldn’t have her in their quarters; they ostracised her. They had tin sheds with proper lighting and comfortable mattresses, and Nora was out in a tent in the mud on her straw mattress with the rats, but she didn’t blink. She wanted to show their noble contribution and she was very proud and very honoured to be able to do that.”

WAAAF cook (Corporal Joan Whipp), 1945. Heysen's portrait of Corporal Joan Beatrice Whipp, depicts her as an immovable tower of strength as she stands, arms folded, in her mess kitchen. Whipp was a cook from the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force.

The conditions were gruelling, and the troops found her unconventional, but she was committed to her work.

“At one stage, she did a deal with one of the surgeons who wasn’t very fond of having her around,” Willoughby said. “She did a picture for him of one of the nurses who he thought was quite attractive, so he allowed her to paint out of the heat and the humidity and in the cool of the whitewashed operating theatre when it wasn’t in use.

“She found it very difficult to work in her preferred medium of oils. She said, ‘My paintings will be old masters by the morning, they’ll have mildew all over them,’ so she worked quickly, sketching and working in watercolours, and building up a large portfolio of sketches.”

Nora carefully annotated her work so that she could work the paintings up into full-scale oils when she returned to her studio in Melbourne.

Nora Heysen at the 106th Casualty Clearing Station at Finschhafen in 1944.

View from sisters' mess, Finschhafen, 1944.

“But this was one of the problems,” Willoughby said. “Colonel Treloar asked her to send work back, and he was not happy with what she sent back. She had the audacity to do a watercolour of the nurses having afternoon tea; it wasn’t heroic, and it wasn’t of this great contribution that they were making, but she felt that these things also informed what life was like and what was going on. What he didn’t understand was that all the big heroic pieces that she was working on were on a much larger scale.”

Nora was also frustrated by her inability to travel to the front because of the danger and the lack of facilities for women.

“She would go to sleep and she would wake up and a rat would be eating through her leather watch band,” Willoughby said.

“The way she describes things in her letters, you just can’t imagine … ankle deep mud, stinking, rotting Japanese food, and decomposing bodies.

“Not long after she arrives at her posting, she set herself up with a piece of board that she found in this bombed-out mission to paint on, and she sat in a foxhole and started to paint … A little bit of time went by and a strange smell was emanating from underneath. She realised she wasn’t on an old log, she was on a dead Japanese soldier.”

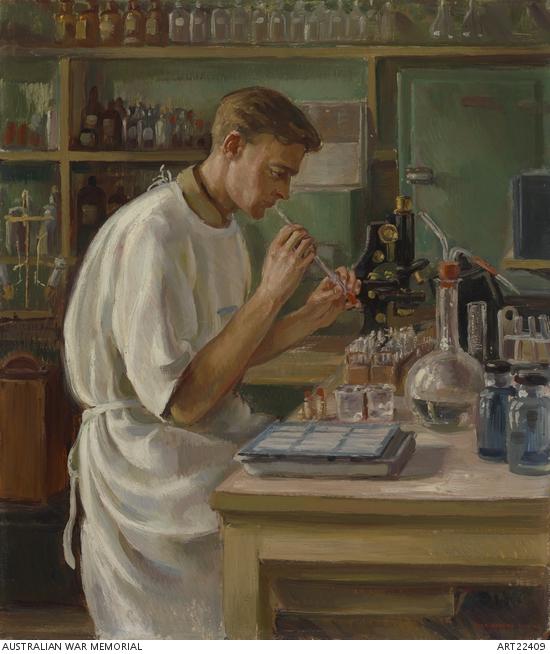

Pathologist titrating sera (Captain Robert Black), 1944. Black was a tropical medicine specialist with the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps.

Nora spent seven months in New Guinea before returning to Australia suffering from severe dermatitis.

“It was terrible,” Willoughby said. “She had every skin ailment that you could get in the tropics all rolled into one, and her skin was just peeling off. It got to the point where they said, ‘We have to evacuate you.’

“Within all of that hardship, she also fell in love with Dr Robert Black, a tropical medicine specialist … but there was a problem; he was married, and he also had a small child.”

When the war ended, Robert returned to his wife and child in Sydney, and would later travel to England to take up a position as a research fellow in Liverpool. Nora returned to her Flinders Street studio in Melbourne to finish her work, but the pair continued to write to each other.

Twelve months later Nora moved to Liverpool and took an apartment ten minutes away from his work.

When Robert left his wife, the two lived together in Sydney for some years, flouting convention and scandalising Nora’s family. They were married the day after Robert’s divorce was finalised in 1953, and were together for 20 years before he left her for a younger woman.

“He broke Nora’s heart completely and utterly,” Willoughby said. “It was a deep love … and he was the only love of her life.”

Nora Heysen drawing assistant pathologist Lieutenant Max Swan.

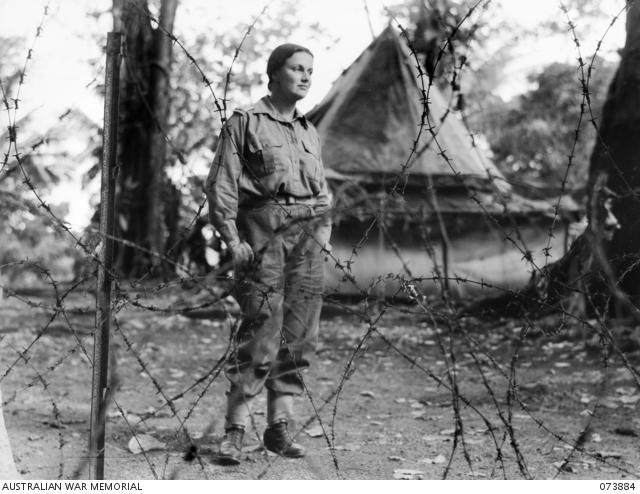

Nora Heysen behind the barbed wire at the nurses' compound at the 106th Casualty Clearing Station.

But even this heartbreak did not stop her passion for her art. “She knew she was an artist and nothing was going to change that,” Willoughby said. “Even if she was washing and ironing and cooking dinners, her work would be there, and it would be waiting for her, and it would embrace her.”

She continued to paint for the rest of life, but never sought publicity. Largely forgotten for many decades, she re-emerged at the age of 78 when long-overdue attention restored her place as a significant Australian artist celebrated by the nation’s major art institutions.

Nora died in 2003 at the age of 92, still living in the house in Hunters Hill that she had shared with Robert Black. Aside from her art, her great pleasures were her home, her cats and her garden.

“Her work ethic was extraordinary,” Willoughby said. “If something had to be done she just pushed through and got it done, and her father taught her that.

“She did live in the shadow of her famous father, and she always asked the question, right up until she was in her 80s, ‘Am I an artist in my own right, or is it because of my name that people pay attention?’”

Today, Nora is recognised for her extraordinary body of work and is considered one of the most significant female Australian artists of the last century.

Join writer Anne-Louise Willoughby for a free public talk, War and love – Nora Heysen, in the BAE Systems Theatre at the Memorial on Wednesday, 10 July 2019. For more information, visit here.

More than 30 wartime works by Nora Heysen in the Memorial’s collection are currently on loan to the National Gallery of Victoria for the Hans and Nora Heyson: Two generations of Australian art exhibition, on display until 28 July 2019.

The National Library of Australia will be hosting a separate event on 9 July, titled Nora Heysen: a portrait by Anne-Louise Willoughby.