'It was death defying, absolutely death defying'

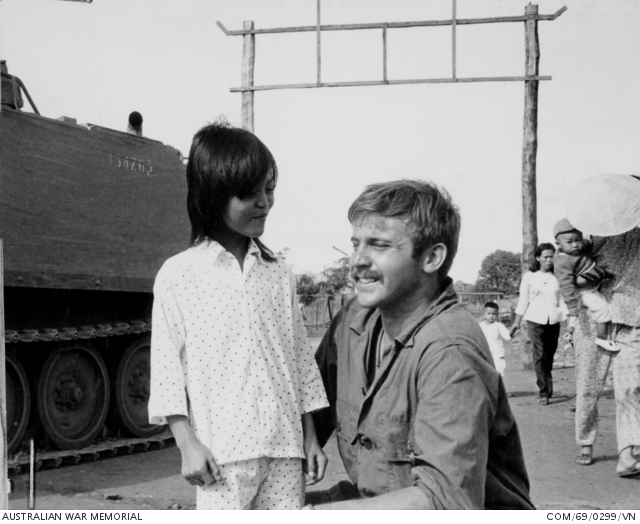

In January 1969, singer Normie Rowe climbed off the back of a Caribou carrying a duffle bag and a guitar.

Australia’s King of Pop, Rowe had been called up for National Service, one of more than 15,000 national servicemen who served in Vietnam during the war.

He had flown into Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport just a few hours earlier. More than 50 years later, he still remembers it clearly.

“Absolutely, clear as a bell,” he said.

“I arrived by 707, courtesy of Qantas, and when I got off the plane we loaded into a Caribou and flew down to Nui Dat.

“I came off the back of the Caribou carrying a guitar and a duffle bag in my service uniform and I always thought the irony of going off to war dressed like this in a commercial jet was surreal.”

The very next day Rowe found himself aboard an armoured personnel carrier headed to a fire support base where troops had been ambushed the day before.

“I was shown my accommodation, and the very next morning at daylight I was to join a resupply convoy to go out to a fire support base and that was when I saw my first dead body.

“I was 21 … and I don’t think it’s describable. I’d never had the experience before and I’ve never had that experience again.

“I was away from Nui Dat from that moment on for about eight weeks, and I was on operation – two different operations – for that whole period of time.

“When I came back I was shown to a tin hut, and the irony of that was that everything was in a line – militarily in line – and my tin hut was offset by about three metres so that they didn’t have to tear down a frangipani tree.

“So outside of my window there was this frangipani tree growing, and every time I smell frangipani or have a vision of it – it’s my favourite scent, my favourite flower, and my favourite plant – it reminds me of the juxtaposition of the beauty of nature and the ugliness of war.

“Of course it was [frightening], and early on it was very frightening. My eyes were bigger than dinner plates…

“Every step we took. Every metre we rolled our vehicles over. Every piece of jungle that we wandered through could be our last moment on the planet. It was death defying, absolutely death defying.”

He would later discover that he shouldn’t have been out in the field so soon.

The renowned war photographer Denis Gibbons had been based at the Australian Taskforce Base at Nui Dat at the time and had accompanied Rowe on his first operation. Years later, he asked Rowe if he thought it was strange that he had been sent out so soon.

“Denis became a really good friend of mine, and Denis said to me, ‘Did you ever wonder why you went out into the field the day after you arrived?’

“I said, ‘No I just thought it was normal,’ and he said, ‘Well, it wasn’t; you always had a familiarisation period, but I got a signal from AAP/Reuters to say that they needed photos of Rowe in the field, so I went to the brigadier officer in command of the taskforce and said I need to get photos of Rowe in the field.’

“And the next day, there I was out in the field.”

Rowe went on to serve with A Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, rising through the ranks to corporal, and commanding an armoured personnel carrier as crew commander. He would never forget the things he saw.

“There were 360 odd days of it,” he said.

“And every day was a different day, but every day was as important as the previous one, or the one after. The great thing is that when I look back, I look back at the happiness and the smiling nature of the diggers that were serving, and the knowledge that they did it with such dedication.”

Australia’s biggest star, Rowe had been at the height of his career at the time. He’d had 11 top 10 hits and was touring internationally, but that had all changed when he was called up and sent to Vietnam.

Years later, he heard that he had been called up in a supplementary ballot.

"Everybody knew about me being called up before I knew because the press was notified before I had even received the notification from the government.

“But I wasn’t prepared to play the PR guinea pig. If I was going to be called up, I was much more interested in being a regular soldier, the same as everybody else.

“Every time they tried to make a publicity stunt out of it, I said no. For instance, when Johny O’Keefe, who was a very big star in the day, came to Vietnam … they wanted to call me out of the field to have photos taken with him.

“I knew John, but they wanted to have the photos taken as a PR stunt, so I said no. If I came out of the field, and my vehicle was hit by a rocket propelled grenade, or if my vehicle hit a mine and the people for whom I would normally be responsible for were hurt or killed … then I could never, for the rest of my life, live with it. So I said no, I’m sorry, I would stay in the field.”

When Rowe returned to Australia, his father told him to forget everything about the war.

“My parents went through the Second World War, and they were constantly petrified that I might have been hurt, I guess, but I never really spoke to them too much about it,” he said.

“When I got back Dad said that the best thing you can do is forget about it – forget you ever went, don’t talk about it in public, blah, blah, blah. But it was some of the worst advice I’d ever received. Dad was going off the Second World War book – where everybody was either overseas or back in Australia working for the war effort. But in Australia we had all these people who were wandering up and down streets … and it was like, ‘Do you even know what you are marching about? We’ve been there, and we know what it’s like.’”

He still remembers arriving home in the middle of the night.

“There were about 20 of us who went home,” he said.

“There was a 707 going back to Australia that had no passengers available and they said, ‘Is there anybody here who is on their last throws of their anti-malarial tablets who would like to go home tomorrow?’ We were all shaking our little vials of pills, saying, ‘Yeah, yeah, we’re here, we promise we’ll take them when we get home.’

“We got onto the Caribou the next morning, up to Tan Son Nhut airport and onto a 707 and were back home even before our families were aware that we were coming home.

“I had done a bit of work in Vietnam shooting some footage and things just for Legacy, and the chair of Legacy, who was also the chairman of Ampol at the time, met me and my mates at the airport, and he said, ‘Welcome home.’

“It was probably one of the most indelible memories that I have. He said, ‘What are you going to do now?’ And I said, ‘Well, we pooled our money and we’re going to get a room at the Sheraton in Sydney – the Sheraton Wentworth – and crash on the floor or wherever.

“We could sleep anywhere by this time, and we all got in a taxi from the airport. It was about eleven o’clock, midnight, something like that, and we got into the Wentworth, and as we were walking through the door, the concierge there said, ‘Are you Mr Rowe? We’ve been waiting for you.’

“I said, ‘How could you? You didn’t even know I was coming.’ And he said, ‘No, we’ve got it all organised.’ The gentleman from Ampol and Legacy had organised a suite for my mates and me, and we thought, ‘Geez, isn’t this nice?’ We felt that at least somebody was thinking of us, and it was a very special moment, but it didn’t happen for everybody, and I just sort of wish that it had.

“And I suppose that’s what the Welcome Home was all about later on … it was always in the back of my mind that not everybody got the welcome home I got.”

Rowe became a leading advocate and spokesman for Vietnam veterans after the war, and was heavily involved in the Vietnam Veterans Welcome Home Parade in 1987 and the dedication of the Vietnam Forces National Memorial on Anzac Parade in Canberra in 1992.

He will be performing as part of the Vietnam Requiem this weekend to mark the 50th anniversary of the Australian withdrawal from Vietnam.

Created and directed by the Australian War Memorial’s musical artist-in-residence, Chris Latham, the Vietnam Requiem brings together Australia’s leading composers and performers in a bid to create a deeper understanding of the Vietnam War through music.

A commemorative work, it will focus on veterans and those directly affected by war, including military and civilian medical staff, entertainers, journalists and photojournalists, the protest movement and the Vietnamese refugees who made new lives for themselves in Australia.

“Who would have thought that this sort of thing could take place, anytime since we came back? And yet it is happening,” he said.

“It’s a really special event – a very important event – in our history, but the most important thing is that we understand the sacrifice and the cost of the freedoms that we enjoy here in Australia.

“Anything that furthers the understanding of what it is like to be an ex-serviceperson of any war, of any deployment, from my point of view is worthwhile being involved in.

“We really need to look after people before their service, during their service, and for the rest of their lives after their service.”

Rowe will be dedicating his performance to his friend, Vietnam veteran Peter Poulton, the chairman of the Vietnam Veterans Welcome Home Committee and the Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial in Canberra.

“Somebody said to me, ‘What are you doing for Anzac Day,’ and I said, ‘Which one?’ For me … Anzac Day is every day and there isn’t a day that goes by when I’m not reminded,” Rowe said.

“You can look at your life and say that wasn’t fair and that killed your career … or you can look back and take from that segment of your life whatever was good.

“The best friends that I’ve got are Vietnam veterans. I’m one of them and there’s an incredible bond. Without those friendships, it wouldn’t have been worth it.

“It’s been a great journey, and I always look at my life like a bedspread. Would I rather a nice 500-thread count Egyptian cotton bedspread of pure white, or would I like a patchwork quilt?

“And I think my life has been a patchwork quilt of great colour and depth, and when I fall off the twig or shuffle off this mortal coil I will just have to say, ‘S***, what a life; what a ride.’”

The Vietnam Requiem will be performed at Llewellyn Hall, ANU School of Music, Canberra, on Saturday 5 June 2021 and Sunday 6 June 2021. For more information, visit here.