Nursing for the British Raj

The interest in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) during the Great War was recently encouraged by the screening of ANZAC Girls and the publication that inspired it, The Other ANZACS: Nurses at War, 1914-1918 by Peter Rees. Both of these focus on nursing services off the Gallipoli Peninsula and on Lemnos and the Western Front in its various guises: hospital ships, field hospitals and casualty clearing stations. We see our girls working alongside the British Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) and as Bluebirds in French military hospitals, courageously responding to the challenges and privations in which they were immersed. However, one must not forget the outposts of India and Salonika where nurses were confronted and challenged in all faculties. Such experiences have not been as widely commemorated and indeed, even the three volumes of the official history of the Australian Army Medical Services during the First World War contain little about them. This blog article attempts to present something of the Women’s experiences.

The Indian Army Nursing Service, known subsequently as Queens Alexandra’s Military Nursing Service in India (QAMNSI) was established in 1888. With the outbreak of war in Mesopotamia in 1916, many QAMNSI were sent to nurse the wounded there. Unable to cope with the casualties, the Indian hospitals hurriedly dispatched for help. AANS Nurses were dispatched to small hospitals all over India and were employed on the British Hospital Ships working from India westwards to the Persian Gulf and eastwards through to Hong Kong and Vladivostock. Although their experiences varied widely, they took it all in their stride.

By late 1918 there were a total of approximately 520 trained nurses in India, consisting of 80 Indian Nursing Service, 120 QAIMNS, and 320 AANS. From July 1916 to 1919, some 560 members of the AANS served in India. They found themselves challenged by cultural differences with the local staff and the English Sisters, nursing exotic diseases in primitive medical conditions and coping with a vastly different climate.

Vera Agnes Margaret Paisley was born in Bunbury, Western Australia in December 1892 and was a certified nurse on enlistment in the AANS on 8 May 1917, serving until 12 November 1919. She had previously worked for three years at the Perth Public Hospital. Embarking for service in India from Fremantle on 5 June, with the rank of staff nurse, Paisley reached Bombay on 18 June. On arrival she was posted to 34th Welsh General Hospital at Deolali, almost 260 kilometres from Bombay.

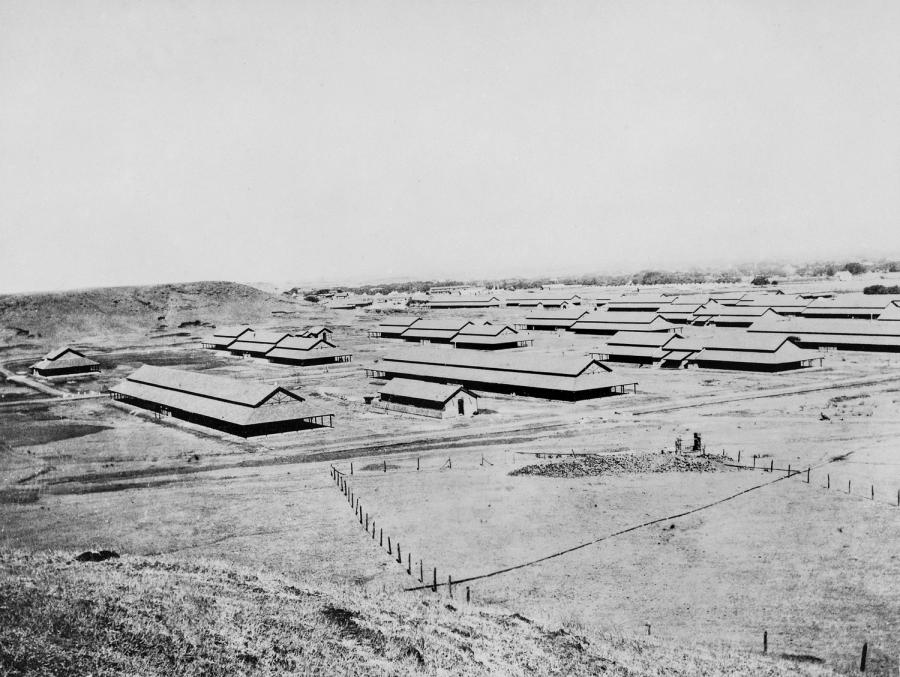

The 34th Welsh General Hospital at Deolali, India. H12551.

The hospital complex consisted of old barracks, stone bungalows and galvanised iron huts spread over a large area nearly two and a half kilometres long by one kilometre wide. Housing over 2000 beds, the nurses cared for patients with diseases such as malaria, smallpox, Spanish influenza and cholera, in trying climatic conditions. Such conditions were too much for some nurses, such as Staff Nurse Emily Clare, who succumbed to Spanish Influenza on 17 October 1918.

The conditions were just as trying elsewhere. When the fighting in the Frontier Wars broke out in 1917, No 18 British General Hospital was established at Rawalpindi and five members of the AANS were sent there: Sisters Emily Gertrude Browne, Vera Steel, Charlotte Joan McAllister, Dorothea Furness and Elsie Katharine Jack. These sisters were working on the outskirts of civilization where the temperature in the hospital at Tank ranged from 46 to 51 degrees centigrade. Situated on the Baluchistan border, the hospital was vividly described by Matron Davis, ‘Here, where no woman has ever been sent before – the last place God ever made – six of the AANS worked in the most appalling heat one could imagine’.

AANS Sisters Browne, Steel, McAllister, Furness and Jack in Tank, India in around 1918. H12556.

There was no relief from such extremes on the hospital ships either, as Sister Scanlon confirmed when she recorded that on one trip to the Gulf the shade temperature on deck was 51 degrees centigrade! Australian sisters also served aboard the Madras, which sailed to Vancouver, then to Vladivostock, where the temperature was thirteen below zero!

Coupled with these conditions was disappointment, as nurses in India felt that their work was scanty at times and unrelated to the War. They often did not consider it to be ‘active service’. Issues with both the Australian and Indian Governments did not ease the matter. Before embarking from Australia they were told that they would stay in India for six months, then move closer to the fighting, however the Indian authorities disregarded such a time limit. Moreover their hopes to at least be able to nurse in Mesopotamia were in vain. The Australian Government scarcely treated them better as their salaries were lower than those of members of the Indian Nursing Service, they were provided with inadequate numbers of light uniforms and had to purchase their own without an allowance and had totally inadequate travel allowances. Unsurprisingly such issues did not help to engender them to their service, yet they overcame them to serve with devotion and professionalism.

Group portrait of the Nursing Sisters, Doctors, Chemists, and Native Orderlies at the Freeman Thomas Hospital in Bombay, India. The portrait was taken in 1918.

Scarlet cape of Sister Mary McDougall. McDougall served at the Victoria War and Freeman Thomas hospitals in Bombay and the 44th British General Hospital in Deolali

As can be seen in the Memorial’s rich collection of photographs, many nurses adapted their uniforms in order to work in the climatic conditions. To cope with the heat some nurses wore rolled sleeves when working and necklines were adapted to the climate by lowering and opening them.

Portrait of two members of the AANS and two patients buying and selling lace in the Victoria War Hospital. The portrait was taken in 1917.

Studio portrait of Staff Nurse Frances Mary Byron MacKellar. MacKellar was posted to the 34th Welsh General Hospital. The portrait was taken sometime between 1917 and 1919.

Interestingly, some dresses appear to be closer to the white of the QAINS. This could be a result of the rough washing they received, or a decision to obtain additional dresses in cooler white cotton. Certainly, nurses such as Staff Nurse Edith Maud Philp adopted white cotton Norfolk jackets and skirts, which they paired with white shoes and hats.

Informal portrait of Staff Nurse Edith Maud Philp standing on the roof of Victoria War Hospital in 1917.

Group of fifteen Australian nurses outside King George War Hospital in Poona.

Other items in the Memorial’s Military Heraldry and Technology Section demonstrate that even though some of the AANS did not value their service in India as highly as they regarded that of their peers closer to the front lines, they showed exceptional devotion and competence in their nursing duties. Principal Matron Gertrude Emily Davis was one of 28 nurses awarded the Royal Red Cross, a military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth for exceptional service in nursing. She was also awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal (First Class) for Public Service in India. This medal was awarded by the British Monarch between 1900 and 1947, to civilians who rendered distinguished service in the advancement of the interests of the British Raj, regardless of nationality.

The Indian experience of nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service was unusual, challenging, exciting but frustrating. Serving in this back-water was disappointing for some, yet they performed with marvellous grace and carried out their duties in a diligent, dedicated and professional manner. It was an interesting chapter in the history of the AANS, one which should not be forgotten.

Further reading:

Rees, Peter & Rees, Peter, 1948-. Other Anzacs : nurses at war, 1914-18 2009, The other Anzacs : the extraordinary story of our World War I nurses, Pbk. ed, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, N.S.W.

Rae, Ruth 2002-05, 'Reading between unwritten lines: Australian Army nurses in India, 1916-19' Journal of the Australian War Memorial (Online), no. 36, pp. 48. Available from www.awm.gov.au/journal/j36/nurses/. [30 September 2014].

Bassett, Jan 1997, Guns and brooches: Australian Army nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

Goodman, R. D. (Rupert Douglas) Our war nurses : the history of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps 1902-1988. Boolarong Publications, Bowen Hills, Qld, 1988.

Rae, Ruth 2004, Scarlet poppies : the army experience of Australian nurses during World War One, College of Nursing, Burwood, N.S.W.

Rae, Ruth 2009, Veiled lives : threading Australian nursing history into the fabric of the first world war, The College of Nursing, Burwood, N.S.W.