How embroidery helped Pat Sullivan survive the war

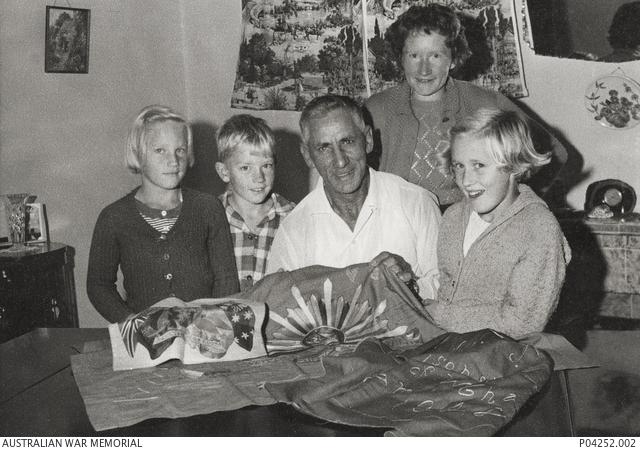

Pat Sullivan showing his embroidery to members of his family. The children are Edith, Roger and Dorothy. There is an unidentified woman at the back.

When Pat Sullivan was captured during the Fall of Singapore, he quickly realised he would need a hobby to help calm his mind and combat depression.

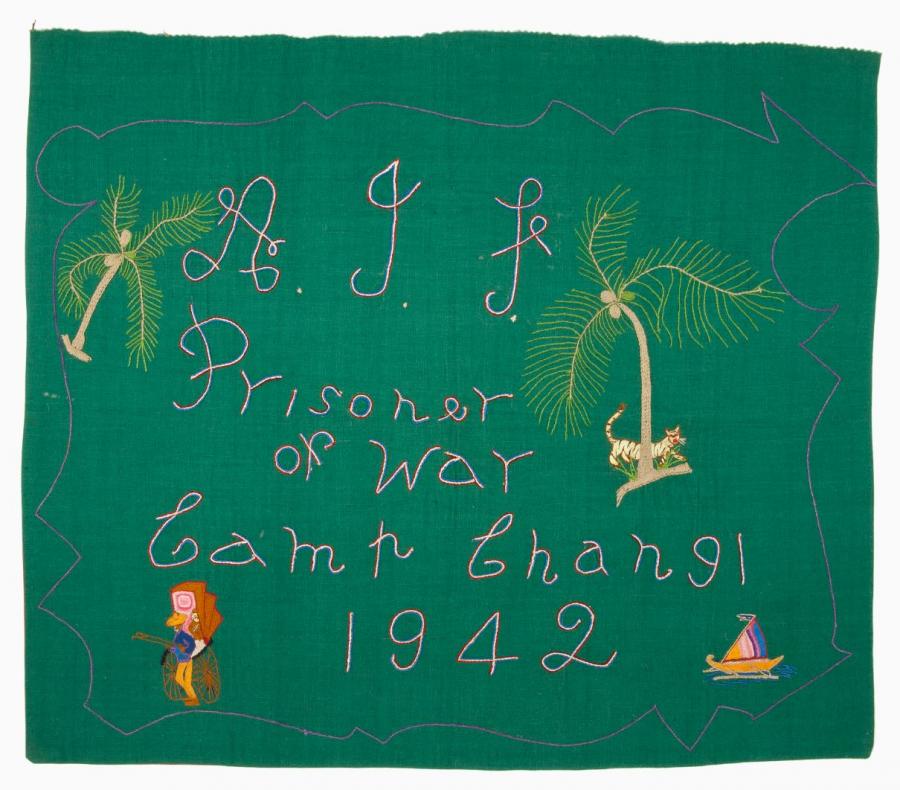

A creative soul who had already produced an illustrated album of poems and memories during the fighting in Malaya, Sullivan took up embroidery while imprisoned by the Japanese at Changi.

A friend from 2/9th Field Ambulance gave him a bag of embroidery cottons he had found during the fighting in Singapore; another prisoner showed him some basic embroidery stitches and helped him with his first attempts at needlework.

Today, the Australian War Memorial holds several examples of Sullivan’s embroidery. They were completed at Changi and on the infamous Burma-Thailand Railway, and are part of an extensive collection of his artworks, photographs and personal effects.

Pat Sullivan embroidered a map of Australia on a Commonwealth Bank cash bag that came from the paymaster of the 2/18th Battalion. Work on the bag took several months to complete.

Memorial curator Garth O’Connell specialises in the Australian prisoner of war experience and is a custodian of the Memorial’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material culture.

A proud Gomeroi man, he is working to identify Indigenous Australians who have served and has a special interest in Sullivan’s story.

“It’s very unusual in that it’s a highly illustrated collection of an Aboriginal serviceman’s experience during the Second World War,” O’Connell said.

“It’s one of the largest collections of Indigenous service and is easily the biggest collection of an Aboriginal prisoner of war in our collection.

“For a prisoner of war, you would normally get a medal group and a badge or something like that; you don’t get photographs, postcards, Bibles, cartoons, poetry, needles, and complete embroideries.

“It’s very, very uncommon … And we’ve got nothing else like this in the collection.”

Pat Sullivan showing his embroidery to Edith, Roger and Dorothy.

Corporal Edward Gordon Patrick Sullivan was born in Deniliquin, NSW, in 1902, a descendant of an Aboriginal woman.

Sullivan was working as a baker when the Second World War broke out. He enlisted in July 1940 and was assigned to the 2/18th Battalion, sailing for Malaya with the 8th Division.

He became one of almost 15,000 Australian soldiers who were captured by the Japanese when Singapore fell in February 1942. Imprisoned at the Changi prisoner of war camp, he was sent to work on the notorious Burma–Thailand Railway in April 1943.

Packed into suffocating metal railway trucks with little food and water, the men were taken to Ban Pong in Thailand and forced to march more than 300 kilometres to camps near the Burmese border. Conditions were extremely harsh: the men were over-worked, underfed and poorly treated; disease and malnutrition were rife, and men died in their thousands.

The tablecloth was the second of Sullivan's works to be finished and took five months to complete.

The cushion cover was the first of Sullivan's work to be finished.

“It was absolutely atrocious,” O’Connell said. “They were part of F Force and it was a terrible, terrible one to be a part of.

“The Japanese were in a hurry to get it done … so for several months there they worked for 18 hours a day in atrocious conditions … and it had the highest rates of loss of all the prisoner of war groups.”

In his New Testament, Sullivan recorded the names of some of the men he knew who died at Hellfire Pass and in the camp at Songkurai.

“It was an absolute abhorrent place to be,” O’Connell said.

Sullivan was one of the lucky ones. He survived more than three years of captivity and returned to Australia where he was discharged in January 1946.

Two of his brothers were also captured by the Japanese; one survived, but the other died in June 1945 on Japanese-occupied Hainan Island, a few months before the end of the war.

Sullivan had a single needle which he carried in this improvised bamboo case.

When Sullivan returned home, his wife Emily entered his embroideries in Albion Park’s first agricultural show, including a map of Australia embroidered on a Commonwealth Bank cash bag that had come from the paymaster of the 2/18th Battalion. He was awarded third place.

He had also completed a cushion cover and tablecloth using linen from curtains found in the evacuated married quarters of the Gordon Highlanders at Selarang Barracks in Changi.

“It’s remarkable that they survived, and in such good condition,” O’Connell said. “He was using anything he could to do his art … but he almost had them taken a few times.”

A British officer intervened when Japanese guards attempted to confiscate one of the embroideries Sullivan was working on, and fellow Australians also helped to conceal his work during other searches.

A trinket box Sullivan made during the war for his wife.

“The Japanese could have looked at these and thought: is there military intelligence in this; is there a message in this flag; or is there a message in this picture of Australia? So they could easily have been taken and just thrown away,” O’Connell said. “But we’ve even got the needle he used to make them and the improvised bamboo case he carried it in.

“Needles were a very big commodity for people in Singapore during the war, and on the black market they were worth a lot of money. You couldn’t just go out and buy clothes when you were occupied by the Japanese; people had to repair things and reuse them, so needles were really hard to get and you can understand why he wanted to look after it. It would have been very hard to get another one.”

The collection also includes a tunic pocket that Sullivan made into a general purpose bag.

“He’s embroidered his name and number onto it and used an Australian army button, but it’s not part of an Australian uniform,” O’Connell said. “We think it could be Dutch, and the only place he could have met Dutch soldiers was up on the Death Railway, so he’s likely to have got it there.

“It really is a remarkable collection and I’m so glad it came here.”