'It was a chance to say goodbye'

Warning: the following story discusses suicide.

If you or someone you know needs help, support is available at Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. If you are an Australian veteran or family of a veteran, you can also call Open Arms, Veterans & Veterans Families Counselling Service, on 1800 011 046.

Every year, a small, remote village on the other side of the world pauses to mark Anzac Day in honour of an Australian Army officer, Captain Paul McKay.

The 31-year-old Afghanistan veteran had been suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder when he travelled to the village of Saranac Lake in upstate New York and went missing in the Adirondack Mountains on New Year’s Eve in December 2013.

His body was found two weeks later, on a rocky outcrop near the summit of Scarface Mountain, following an extensive search in sub-zero temperatures. He had died of hypothermia and exposure, the coroner later ruling his death a suicide.

Clyde Rabideau was the Mayor of Saranac Lake at the time. He announced the news of Paul’s death on Facebook that afternoon. Within hours, the post had been viewed and shared thousands of times, with locals writing to express their sorrow at the loss of an Australian soldier so far from home.

“I am grieving today,” Rabideau wrote.

“A young man … a soldier from Australia … somehow inexplicably chose Saranac Lake to be his final resting place.

“I only know him by his photographs.

“He looks handsome, virile and strong … not unlike my son and [the] sons of so many readers of this post … yet he decided to cross the globe and trek onto our local mountain, where he died.

“It strikes home to me and many here. May he rest in peace.”

The mayor took the unusual step of declaring 25 April 2014 the first Anzac Day in Saranac Lake, after a pledge to honour Paul and others who struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Clyde Rabideau, left, led a hike up Scarface Mountain on Anzac Day 2014 in memory of Paul.

Rabideau led a hike up Scarface Mountain on Anzac Day, climbing the mountain in the early hours of the morning to lay a poppy where Paul’s body had been found.

“One of Captain McKay’s friends asked that I lay a single poppy in his honour in [an] appropriate place on Anzac Day,” Rabideau told reporters at the time.

“It is a unique and very special day … not just in Saranac Lake, but in two other nations that have had our back — and we theirs — for over a century.”

The climbing party included US military veterans, the Saranac Lake police chief, and members of the parks and forest ranger service, who had led the search. They gathered rocks to create a memorial cairn for Paul and placed a blue ribbon and a poppy on it.

“We said some prayers and toasted Captain McKay with some Australian beer,” Rabideau said. “It was a nice, simple, solemn service.”

The community of 5,500 then held a special Anzac Day ceremony at its First World War memorial, with Australian veterans in attendance.

“Captain McKay’s death profoundly affected many in our community,” Rabideau said.

“We asked ourselves ‘why us?’ over and over again as we were alerted to Captain McKay’s psychological state.

“It is our hope that his memory will raise awareness of post-traumatic stress...

“PTS was and remains an important issue for us as a nation and an extended family to understand, to recognise and to treat.

“Together, as a larger family, it is my hope and aim that we can help many of our brothers and sisters reintegrate and 'come back home’.”

Every year, Saranac Lake commemorates Anzac Day in memory of Paul and those who served. On the left is Paul's friend Lieutenant Colonel Sam Benveniste, the only ADF member who knew Paul personally who has attended the Anzac Day ceremony.

Paul McKay was born in Adelaide, South Australia, on 17 November 1982, the son of Angela and John McKay.

A highly intelligent and disciplined student, he was studying law and commerce at the University of Adelaide when he joined the Army Reserve’s Adelaide Universities Regiment in December 2004. While most reserve officers take two to three years to complete their training, Paul finished his in just 13 months.

Major Duncan Hains remembers the time fondly.

“Paul joined our cohort towards the end of 2004 and we became good mates,” he said.

“[He was] intense, and I don’t mean that in a bad way.

“He was very, very focused, and he had a really dry and wicked sense of humour, but when he put his mind to something, he was absolutely focused on achieving it.”

The pair would often go running together, hiking to the summit of Mount Lofty, and racing each other to the top.

“Sometimes it was Waterfall Gully, sometimes Chambers Gully, and often a fully laden pack was involved,” he said.

“The Waterfall Gully run he and I did goes all the way up to the Mount Lofty Summit, and you’re working hard to get up there in under 45 minutes. Most people do it in about 60 minutes just plodding along, but he got up there in 28 minutes with me not far behind.

“I was throwing up by the time I got there … only to find him just leisurely staring at the view of Adelaide as though he’d just strolled up…

“When he was committed to doing something, he just threw his mind behind it.”

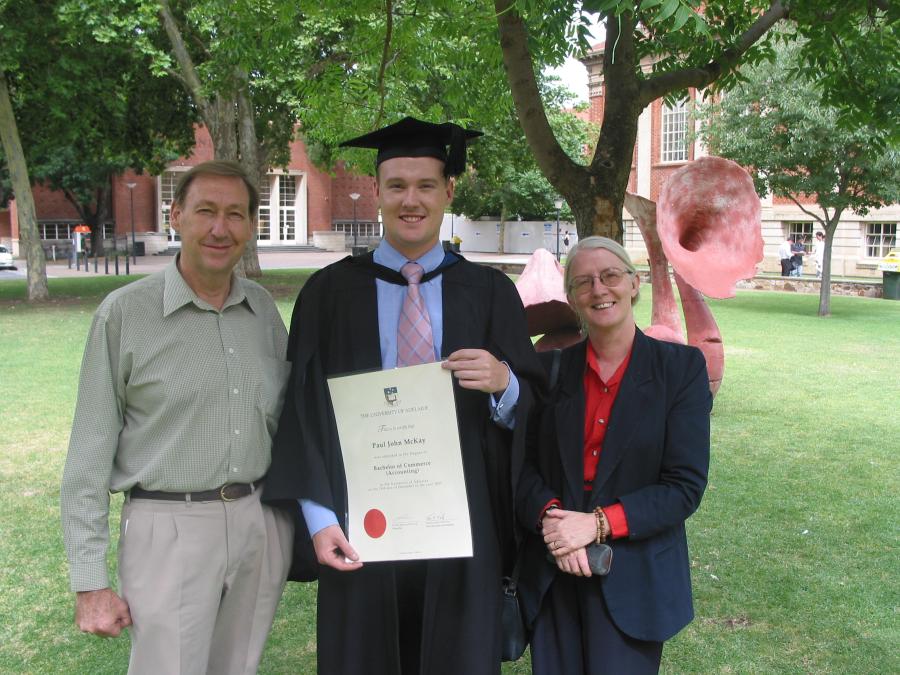

Paul pictured with his parents, John and Angela, in Adelaide.

His friends in the regiment called him Reggie or Reg, as in “Regimental” or highly disciplined and by the book.

“I think he relished the nickname because it took the piss a little,” Hains said. “It represented the characteristics he aspired to always espouse, but it also reflected dependability too; he could always be relied upon.”

A high achiever, Paul hoped to pursue a career in the law while serving in the reserves and had long-term aspirations of entering business or politics. His friends and family had no doubt he would achieve both.

He finished his law degree with honours in 2009, and was admitted to the bar, but then almost immediately quit, to pursue a full-time career in the Regular Army instead.

He transferred from the reserves to the Regular Army in January 2010, and was posted to the 1st Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, based in Townsville.

His friend Major Matt Jones has fond memories of meeting Paul while they were serving together as young platoon commanders in Charlie Company, 1RAR.

“One of the things you were struck by, pretty early on when you met Paul, was that he had this drive and energy,” he said.

“He’d studied to be a lawyer, so he was this blend of the academic and the officer. Studious, and well-read, he would bring all that knowledge and energy into his work, genuinely wanting to make things better for his soldiers.

“He was extremely physically fit, which turned out to be one of the cornerstones of his personality, and how he liked to spend his free time – hard training so he could lead from the front.

“He hated to be idle, and needed to be doing something and doing it the right way, as he saw it. That commitment and sense of what was right left an indelible mark on those around him.

“Paul, Andrew [Evans] and I became friends during our time as Platoon Commanders in Charlie Company and on Rifle Company Butterworth. Being young blokes with a lot of responsibility, going through the same challenges, dealing with the same problems, it created a bond…

“We were all just poor ‘subbies’ at the time so we’d take turns going over to each other’s places after work, have a few drinks and whinge about work. Inevitably, that would see us ‘solving’ all the Army’s problems over the course of the discussion as I forced Paul to listen to ‘70s rock.

“It was over those conversations you really got to know Paul and how fiercely he cared for his soldiers, and wanted to make things better for them.”

Paul McKay: "He could always be relied upon."

When Paul deployed to Afghanistan in May 2011, he was based at Tarin Kowt in Uruzgan Province. As the evening Battle Captain in the command centre at the Combined Team Uruzgan Headquarters, he was in charge of coordinating responses to any attacks or incidents that occurred in the province.

He was on duty in the tactical operations centre during the ‘green-on-blue’ attack at Patrol Base Sorkh Bed on 29 October 2011. Without warning, an Afghan soldier opened fire on a group of Australian soldiers who had been tasked with mentoring the Afghan National Army, killing three Australians and an Afghan interpreter, and seriously wounding seven others.

In the aftermath, Paul’s response was to work even harder, working 12 to 16-hour days on little or no sleep.

Friends and family say he was “never the same person again” after Afghanistan. When he returned to Australia in January 2012, he was “troubled and lived in a world of silence and sorrowful memories”, a shadow of his former self.

On 29 December 2013, Paul flew to the United States, eventually making his way by bus to Saranac Lake. He had never travelled to America before and had left his home in Canberra without a word while on annual recreation leave from the Army.

His family and friends didn’t even know he had left Australia.

Paul McKay: "Studious, and well-read, he would bring all that knowledge and energy into his work, genuinely wanting to make things better for his soldiers."

On New Year’s Eve, Paul left Saranac Lake and walked along the road towards Lake Placid. He had sent an email to his father the night before, leaving him all his possessions, before leaving Saranac Lake on foot to climb Scarface Mountain – named after its massive scar, a rocky ledge covered in snow for most of the year. Even in summer, the scar is clearly visible. Paul also had scars - but Paul’s scars were all on the inside.

He was last seen walking along train tracks near Ray Brook, dressed in snow pants and a winter jacket, carrying a large backpack.

Before long, a polar vortex hit the region and temperatures plummeted to minus 30 degrees. Local police, park rangers and volunteers searched the mountain in sub-zero temperatures after his father reported him missing on 3 January 2014.

Paul’s father had traced the email Paul had sent to a Saranac Lake hotel and had called the Saranac Lake police. In the email, Paul had told his father that everything was okay, but that he had some “housekeeping issues” to clarify. What had followed was a two-page list transferring all his belongings to his father. When his family went to check Paul’s apartment in Canberra, they found his dress uniform and medals laid out on his bed, his ceremonial sword at its side.

Paul’s body was found on a shoulder of Scarface Mountain on 15 January by forest ranger Scott van Laer.

It was meant to be his day off, but he had been mulling over an idea, so he walked out of his back yard, up into the woods, and worked his way towards an ice floe, covered so thickly with evergreens that the search helicopters couldn’t see through them.

“When I started out that day, I didn’t believe I was going to find him,” he said. “I thought there was no chance.”

At first, he thought he had stumbled across an illegal hunting camp, having noticed something off to the side that wasn’t quite right.

“And then I got closer,” he said. “And I thought, ‘Oh. We’ve ended the search.’”

Each year, the people of Saranac Lake continue to pay tribute to Paul after he went missing on Scarface Mountain in the Adirondack Mountains in Upstate New York. Photo: Whitney MacDowell Morgan

On 23 January, a formal procession wound its way solemnly through Saranac Lake as a police escort accompanied Paul’s body to New York City, from where he was flown home to Australia. Pallbearers included police, forest rangers, and veterans; schoolchildren lined the streets of Saranac Lake and Ray Brook to pay their respects as temperatures dropped to minus 20 degrees.

Mark Simkins had served as a medic in the US military in the 1970s and had volunteered to escort Paul’s body home. He and his wife Janet have a deep connection with the mountain and had been heavily involved in the search.

“Why Paul picked Saranac Lake, we will never know, but he did,” Janet said.

“When Paul went missing, everyone tried to trace his steps, and when it was believed that he might have gone up Scarface, people went looking.

“When Scott Van Laer found Paul, the community had a sombre reaction. I guess we had all hoped he had just moved on ... and sadly, he had.

“Since then, Mark has walked up to Paul’s cairn every Anzac Day.

“He will forever pay his respects, and salute Paul.”

Paul's friend Andrew Evans at the Last Post Ceremony commemorating Paul's life.

Paul’s friend Andrew Evans shared his story at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating his life.

“I still remember him every day,” he said at the time. “Occasionally they are sad and mournful thoughts at losing a brother and my closest friend. Other times they are happy memories.

“What I’ll always remember fondly about Paul is that he was never afraid and always up for a challenge. He did what he wanted to do, on his own terms.

“Despite the pain, that is how I try to remember him. Every day. Even if only for a few moments.”

A friend who climbed the mountain sent a note to Paul’s parents afterwards, along with a photo of the memorial cairn and cross in the shadow of the boulder where he died.

“It was a very quiet spot,” he wrote. “Sadly, I didn’t find Paul there. I think I lost him a long time ago.”

His friend Duncan Hains climbed the mountain in January 2019, placing a flag where his friend died.

“It was pretty emotional,” he said.

“When we were all posted to units around the Brigade, we’d still catch up as naïve young Second Lieutenants and then Lieutenants and solve the Army’s problems over a few steins and a schnitzel.

“But after Afghanistan … he was just very distant…

“I remember exactly where I was [when I found out he was missing]. I got a call from [the Army] to ask whether we’d any contact with him … and then there was just a flurry of text messages and phone calls.”

Climbing the mountain was his way of saying goodbye.

“It was closure, more than anything, and it was a chance to reconnect on a number of missed years,” he said. “It was a chance to say goodbye and to try to understand.”

Paul's friend Duncan Hains climbed Scarface Mountain in January 2019.

Matt Jones was in Thailand when Paul went missing. He had reached out to the local police chief, sharing whatever information he could in an effort to help with the search.

“I thought perhaps he'd gone travelling to physically test himself … to put things behind him … certainly climbing a mountain during a storm seemed to fit ... but I wasn’t willing to accept that he never intended on coming back.”

He retraced Paul’s steps the following year, climbing the mountain on the anniversary of Paul’s death to pay his respects and say goodbye.

“Paul was one of the hardest working people I had ever known but that came with a cost; he tolerated a lot without complaint when others might have asked for help,” he said.

“He was always fiercely proud of being part of a team, of being an infantry officer and being in the Army.

“From what little he would talk [to me] about his time in Afghanistan, he had this misconception that he had let people down … but you didn't fail us mate…

“We just didn't get a chance to tell him, or he couldn't hear us.”

Duncan Hains showing his son Paul's name on the Roll of Honour at the Memorial.

The new mayor of Saranac Lake, Jimmy Williams, has vowed to continue the Anzac Day tradition, hiking Scarface Mountain on 25 April and performing a Dawn Service in honour of Paul.

A former US Navy Seal, Williams has worked closely with Australian SAS soldiers and commandos and has an intimate understanding of war, and the great costs levied on all involved.

“This year's ceremony was an intimate one, held at dawn in keeping with the Australian tradition,” he said.

“It was a beautiful Adirondack morning alongside ... Lake Flower that flows through our small mountain village.

“As steam rose from the lake waters, it was an opportunity to stop everything, to think, remember, thank, and respect all of those who gave so much for the good of the rest of us.

“Being such a small community, Paul made the hardships of war real for many of our citizens.

“I believe it is healthy to be reminded of how fortunate we all are, and that there are strong men and women who gave all to make this beautiful life possible.

“For myself, I felt briefly connected again to those I will not see until the next life.”

In June 2014, Paul’s parents made the difficult journey to Scarface Mountain to scatter their son’s ashes on the quiet, wooded peak where he had chosen to die.

His mother Angela thanked the community for the “outstanding care and compassion they showed to our dear son, Paul.”

She said it was an “amazing mark of respect” that the village had chosen to commemorate Anzac Day. She and her husband are forever grateful for those who continue to remember and pay their respects to their son.

“It is a wonderful gesture and one our son Paul would be proud of,” she said.

“Sadly, Paul was never the same when he returned from Afghanistan. He retreated into himself and lived in a world of silence and sorrowful memories.

“It was tremendously sad for us, as his family, who could remember such a fun-loving person, to see him with no life in his face and no light in his eyes.

“It was a testament to his bravery, his moral courage and his great inner strength that he lasted as long as he did. But he never complained, which ultimately was his downfall.

“We have no idea why Paul chose Scarface Mountain to be his final resting place on Earth, but six months after Paul was found there, we honoured his wishes when we climbed the mountain.

“As we scattered his ashes around the rocks a slight breeze caught some and blew them up in a spiral. It was as if we were releasing Paul’s spirit where he wanted to be, free now to roam on Scarface Mountain.

“Our son was in their town for less than 24 hours. He hardly spoke to anyone. But he has left a lasting impression on the community … The locals took him into their hearts and identified him as one of their own.

“This is small town America at its best.

“They are absolute class.

“We hope ... this article might give [people] a better understanding of the pressures and stress that members of the ADF experience in their military careers, and especially when on deployment.

“For any serving or ex-serving ADF members who read this article, if you identify in any way with our son, Paul, then please seek assistance so that you too do not become another statistic.

“The Royal Commission into Veterans’ Suicide continues for another year and is already highlighting the high mental stresses involved with being a member of the ADF and we sincerely hope it will bring about recommendations and solutions that will support our ADF members.

“Perhaps it is only fair that Paul himself should have the final words ...

“Just before boarding the bus to Saranac Lake, in the final letter he wrote to us, he finished with the words: ‘I am not suicidal, nor am I weak, but basically fighting an unwinnable battle.’

“In the 31 years of his short, but amazingly talented life, it was the only battle he ever lost.

“While Paul’s brave struggle is over, we hope that his legacy will continue to live on.”

The Australian War Memorial has commissioned a work of art to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war and military service. The sculptural installation, For Every Drop Shed in Anguish, by artist Alex Seton, will provide a place in the Memorial’s Sculpture Garden for visitors to grieve, to reflect on service experiences, and to remember the long-term cost of war and service. A field of sculpted Australian pearl marble droplets, it will be made by the artist over the next two years and will be installed in the Sculpture Garden in 2023. For more information about the Sufferings of War and Service sculpture, visit here.

If you, or someone you know requires support, please contact:

Defence All-hours support line – The All-hours Support Line (ASL) is a confidential telephone service for ADF members and their families that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week by calling 1800 628 036.

Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling Service provides free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. They can be reached 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit the Open Arms website for more information.

DVA provides immediate help and treatment for any mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. If you or someone you know is finding it hard to cope with life, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254. Further information can be accessed on the DVA website.